A pervasive myth regarding low-wage workers is that they are just school kids or uneducated and lack ambition. This false narrative is worse than untrue -- it stigmatizes many good American workers and families. At The Fairness Project, an organization focused on bolstering economic fairness ballot initiatives across the country, we are taking these myths head on.

Perhaps nothing does more to explode this myth than the fact that there are over one million military veterans who would benefit from an increase in the federal minimum wage to $10.10 an hour, and many more who would benefit from even higher minimum wages being pursued by our partners in California, Washington, D. C, and Maine.

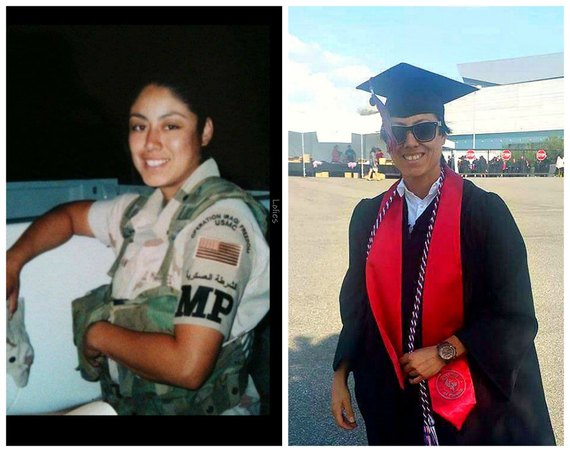

Take Marine veteran, Yolanda Duran.

Yoli served four years as a military police officer in the Marines and was honorably discharged in 2004 as a Corporal. In 2000, just one year before 9/11 and multiple wars in the Middle East, Yoli found herself a freshman in college with mounting bills to pay. "I enrolled in college, rented an apartment and had to get a job to pay rent. Work kind of consumed a lot of my time and I was really tired in classes and wasn't doing so great in school."

Not long after, a recruiter from the Marine Corps contacted Yoli. "He was very, very persistent," Yoli told me. "He just kept calling and calling and finally I gave in and decided to see what he had to say."

What the recruiter didn't know was that Yoli had dreamed of being a police officer nearly her whole life. As a little girl she used to take the plastic rings that held together soda cans, and use them as pretend handcuffs on her friends and family. She listened to the recruiter and then she made him an offer, intent on securing the position she wanted, "The only way I would sign that paper was if I could become military police," she told me.

The recruiter delivered and arranged for her to become a military police officer, and Yoli was on her way, first to boot camp in South Carolina, and then Yuma, Arizona, where she was stationed. "I expected the Marine Corps to teach me, guide me, direct me. I looked forward to learning whatever I had to learn for my career field. That way when I was done with the Marine Corps I could pursue the career I went in for."

In 2003, Yoli was deployed to Iraq, where her days consisted of, "everything and anything, waking up early, packing sandbags, preparing gear, building housing for fellow Marines, transporting gear, staying alert, and listening to commands."

Throughout her service, Yoli saw herself growing. "I've always been a very shy individual, but I learned how to come out of my shell, how to be a leader, how to be responsible, how to speak with people, how to be brave in the sense of interacting with others. It taught me the importance of just doing what has to be done, of being motivated, of doing things on my own without being told what to do. The importance of going a little bit above and beyond."

When she returned from her deployment, Yoli started to think and plan for her future. She purposely took as little leave as possible during her enlistment, so she could bank up paid time off and have extra time to apply for school and look for jobs. But returning to civilian life was difficult, like it is for so many of our veterans. "It was a little bit of a shock to leave the Marine Corps. You have done so many things a certain way for four years, repeatedly and repetitively, you get so used to it. There is a lot of adjusting when you get back home."

After being frustrated in her initial classes and still struggling to adjust to civilian life, Yoli once again pursued her lifelong dream of being a police officer. She applied to the LAPD but wasn't able to make it through the difficult process on her first try. She was unemployed and didn't have the luxury or savings to wait around and apply again; she needed a source of income. "When that happened I got discouraged and left my dream of being a cop and just kind of went forward."

Yoli fell into a familiar cycle for low-wage workers: "I worked so much that school and being a cop were no longer in my mind. It was just, ok well, this is where I'm at, this is what I'm going to do I guess, so I worked at some not-so-great paying jobs but just trying to make enough to get by."

For the next ten years, Yoli bounced around between low wage jobs, where she made between $10 and $12 an hour. She worked in any job she could find -- for a company that made wiring and later in merchandising, stocking the shelves in large retail stores. Yoli had a distinct feeling during this time, common among low-wage workers: "The pressure was just to live -- gotta eat, gotta pay rent, gotta put gas in your car, gotta work to be able to do the things you want to do. The pressure was to make money to live."

Today, Yoli is still working toward her American Dream, utilizing the skills and never-quit attitude she learned in the Marine Corps. She is rightly very proud of the fact that she recently graduated with a B.S. in Information Technology, and hopeful this will lead to a better job. But she remains only cautiously optimistic. "I'd like to get a career in the field that I studied but I don't feel super confident. I'm going to apply to different jobs in the IT field but also look at probation officer positions and go from there."

In the meantime, more than 10 years after she returned from Iraq, Yoli is working two jobs to cover her expenses, "I'm not getting any younger," she told me, "I want to make more, need to make more."

Yoli remains proud of her service and grateful for the opportunity that she had. "I'm very thankful for the Marine Corps. I had a great experience. I met great people, people who I consider to be my brothers and sisters. Without the military I wouldn't have gotten this degree, they paid for it. But it is hard when you come out of the service. It is pretty difficult to adjust to a different way of life, but that's what I'm doing right now, taking what I learned from the Marine Corps and moving forward. Trying to be positive and go bigger and be better."

Veterans like Yoli aren't looking for handouts, but they need more from our economy. It's what we too often forget, or ignore, or refuse to believe about millions of Americans who are caught in a low-wage cycle. They are veterans, parents, brothers, sisters, and friends. They are still chasing the American Dream. Isn't it time we, collectively as a country, made sure they can earn a living wage and have a fair shot?

Visit our website to learn more about what you can do to help fight for a more fair economy: www.thefairnessproject.org