Do you remember fifth grade? Were math facts drilled into you? Were you expected to explain your intellectual process when problem solving? Were your movements in and out of the classroom highly monitored? Were you and your classmates given the authority to make your own rules?

Depending on your recollection, the scenario that sounds most familiar to you may reflect the socio-economic class of your parents. That observation was put forward in Jean Anyon's famous Social Class and the Hidden Curriculum of Work where she observed classroom practices in what she described as working class, middle-class, affluent professional and executive elite schools. Anyon wrote: "In the contribution to the reproduction of unequal social relations lies a theoretical meaning and social consequence of classroom practice." Or in other words: your family's status determines your schooling, which determines your place in an unjust society and economy.

In a recent excellent episode of This American Life, Is This Working Chana Joffe-Walt explores the question of discipline in urban public schools. She contrasts approaches by a zero tolerance, no-excuses-style charter school and Lyons Community School in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, which has built its school culture on an ethos of Restorative Justice. (Lyons's peer mediation program and their student-led Justice Panel (which isn't, technically, a restorative justice practice but it is an alternative-to-suspension) are shown in the documentary Growing Fairness and can also be found in this case study from the Dignity in Schools Campaign-New York.

The contrast of the two schools in the episode is powerful and provocative, but it may not be an altogether apples to apples comparison. Charters are notorious for recruiting students with more savvy, resourced parents from the publically-run school system, by imposing admissions hurtles that makes it "tough for students who struggle with disability, limited English skills, academic deficits or chaotic family lives to even get into the lottery." Lyons, on the other hand, has been impacted by this type of selectivity in that it accepts a large number of "Over The Counter" students who wouldn't apply for (and much less succeed at) a charter school that lacks services for those with special learning needs. And yet it's these kids, the ones dumped by the system, the ones most "at-risk" for poverty, dropping-out and incarceration, who, at Lyons, are being privileged with the voice and authority of resolving their own conflicts, just like the students at the elite-executive school described by Anyon. Is This Working? asks the question without asking it: Are these educators hurting low-income children by inculcating them with a sense of entitlement and voice that the outside world doesn't allow them to have?

Back at the charter school, teacher Rousseau Mieze describes the creepy feeling he got watching black students get positive responses for their extremely (and, I would say, unnaturally) obedient behavior at a rest stop during a school trip. Many of us with liberal arts degrees are familiar with Michel Foucault's argument that discipline creates "docile bodies" that function in factories, ordered military regiments and school classrooms. There is a real fear-based tension among parents and educators of black children about how to raise kids in a society that is in denial about its racism while black men are stopped-and-frisked, arrested for harmless-but-criminalized actions and gunned down on a regular basis by police. Given these fears, should parents and educators train children to be submissive and obedient in order to stay out of jail, or simply to survive? Or should they be treated as full human beings entitled to freedom, self-determination and voice in our society? To me it's a question with a clear answer, but I have to say I understand a parent's fear that might make them hesitate to choose.

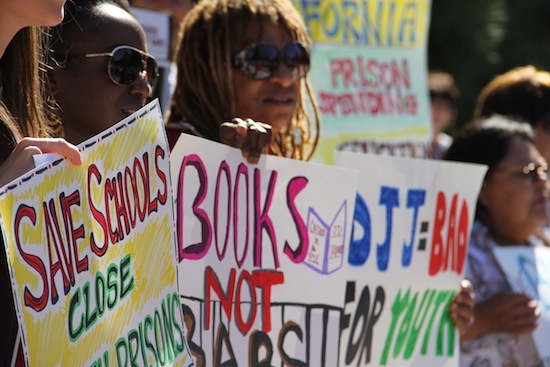

In Is this Working? we hear about teacher fears, similar to parent fears, of their black students being incarcerated--and those fears being realized. In some sense, the system is working. The divesting of public education and the boom of the Prison Industrial Complex is working great for the multitude of corporations, CEOs and organizations with profitable contracts in those sectors. But when, as Americans, we have muddled and conflicting thoughts about what schools are for, we become paralyzed in questioning what the right way is to orient students to not only learning, but persevering. Just as in parenting, unless we've extensively studied childhood development, we can really only draw from our own experiences. In both child-rearing and education, we've all been trained to think a certain way.

It is the critical thinkers and disobedient students who reject this training, and in poor, urban communities the consequences for resistance are dire. As I listened to the reflections of the staff at Lyons, I was relieved to hear a dean question the idea that students were inappropriate to react with fury at a police officer's hostile treatment of their friend. Some of us continue to hope that all schools can be transformed to give children a basic sense of pride and respect for themselves, a voice, and a sense of entitlement. The challenge, of course, is for the rest of society to keep pace.