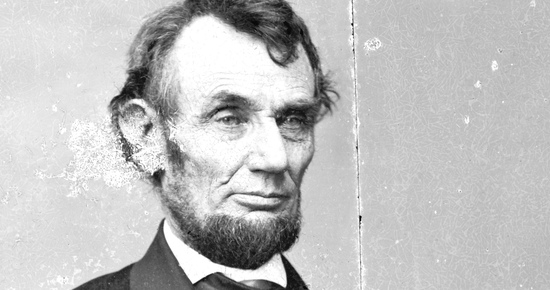

Tuesday, November 19, marks the 150th anniversary of the Gettysburg Address. Much will be made of the most influential speech in American history. I will travel across the country to commemorate President Lincoln's words on the site where he delivered them. Others will mark the occasion at local events across our nation. Still more will participate in virtual ceremonies around the world.

Few will realize that the Gettysburg Address was a flop in its time, and that Lincoln went to his grave believing he'd blown a crucial opportunity. To understand how he felt, we must place ourselves in his size 14 shoes.

Lincoln's remarks were delivered at the dedication of a new National Cemetery in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania -- a cemetery made necessary by the astounding number of deaths that occurred on those grounds a few months before in July, 1863. Though most historians agree that the Battle of Gettysburg marked the turning point of the Civil War, Lincoln himself felt no such optimism in the wake of General Robert E. Lee's escape from the North, with his Army of Northern Virginia battered but intact.

Lincoln was furious that his newly minted commander of the Army of the Potomac, General George Meade, had failed to pursue Lee's men after the battle. He correctly realized that the war would drag on for years, and that even the loyal citizens of the North would recoil from the ever-mounting losses of their sons, husbands and fathers.

A series of riots soon broke out in New York that caused more casualties than many battles. Lincoln came under tremendous pressure to simply end the war, and accept slavery as it was before the fighting started, so long as the Union could be restored. Others espoused peace at any price, even if it meant sharing the continent with the Confederate States of America, thus rendering meaningless the sacrifice of all who had thus far died for the cause of Union -- a cause that Lincoln had elevated earlier that year by declaring an end to slavery in all Confederate lands.

It was under these circumstances that Lincoln struggled to keep his armies supplied, and his citizenry committed to the cause. No man ever worked harder at his job, and Lincoln rarely left the capital for any but military exigency. When it was decided that a new cemetery would be created for the men who fell at Gettysburg, no one could be sure that the Commander-in-Chief would be able to attend the dedication. The Gettysburg "Address" was thus entrusted to the august Edward Everett, a former Governor of Massachusetts and President of Harvard University.

The organizers hoped the President would attend, and to this end they adopted a twofold strategy. First they invited Lincoln's pal, Ward Hill Lamon, to be Marshal of Ceremonies at the dedication. Lamon was one of Lincoln's law partners in Illinois, and the only friend he brought with him to Washington. Lincoln liked having Lamon around because he played banjo and shared the President's ribald sense of humor. After the first attempt on Lincoln's life in 1861, the burly Lamon appointed himself the President's bodyguard and served faithfully in this capacity throughout the war, saving Lincoln's life repeatedly and accompanying him everywhere. He would have been present at Ford's Theatre in April, 1865 as well, but Lincoln sent him away three days before the final, fateful night.

Lamon thus had unique access to Lincoln when he was appointed Marshal of Ceremonies for the cemetery dedication, and it was only a few weeks later that Lincoln accepted the official invitation from the organizers to deliver "appropriate remarks" at the event.

In his Recollections of Abraham Lincoln 1847-1865, Lamon wrote:

Mr. Lincoln told me that he would be expected to make a speech on the occasion; that he was extremely busy, and had no time for preparation; and that he greatly feared he would not be able to acquit himself with credit, much less to fill the measure of public expectation.

At the event itself, Edward Everett spoke magnificently for two hours. Such length was standard for the era, and the speech was well received by the thousands in attendance. Marshal Lamon then stood up and introduced "The President of the United States!"

Lincoln received applause, and then took his customary pause before addressing the audience. All knew he would say less than Everett, but no one expected what came next. Photographer Alexander Gardner figured he had at least 10 minutes to capture the President delivering his remarks, and took his time setting up for the important shot. He, and we, never got that photo.

President Lincoln spoke a mere 272 words, and then sat down. For the people of 1863, it was a baffling disappointment. That his 10 sentences carried within them poetry, meaning and transcendence, was lost on nearly everyone present. Instead, they were simply shocked that he was already done. Lamon wrote:

[Mr. Lincoln] said to me on the stand, immediately after concluding the speech, "Lamon, that speech won't scour! It is a flat failure, and the people are disappointed." He believed that the speech was a failure. He thought so at the time, and he never referred to it afterwards, in conversation with me, without some expression of unqualified regret that he had not made the speech better in every way.

Lincoln's Gettysburg speech was a flop not only in his opinion, but also that of Lamon, Secretary of State William Seward, and most American newspapers. Typical was the Chicago Times' assessment: "Silly, flat, and dishwatery utterances." Ironically, it was the British press that first recognized the grandeur of the speech. After Lincoln's death, the American public caught up, finally recognizing the literary treasure he had bequeathed to us.

Over the years, Lincoln's 272 words have grown into an American institution, memorized by generations of schoolchildren. To truly appreciate the speech, however, one must imagine the losses leading up to it. The Civil War would eventually take some 700,000 lives in a nation of 30 million. In today's numbers, that would be a loss of over seven million soldiers -- a holocaust beyond comprehension.

In the midst of all that tragedy, Lincoln struggled for meaning. The tragic losses to our nation had to mean something more than a war won, or even a Union restored. All that death had to find purpose beyond 1863. It must end slavery forever -- a fundamental change in the human condition. To the extent that slavery still exists anywhere in the world, Lincoln's mission still exists too.

This month, the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum in Springfield, IL presents a touching exhibit, in which individuals from all walks of life, from American presidents to fifth-graders, write their own 272 words on Lincoln, the Address, or the ideals they hold most dear.

I was deeply honored to participate, and in my 272 words, I compared the Civil War's horrific death toll to the European Holocaust in which my grandfather was murdered. Many of us struggle to find meaning in such events, and Lincoln's words provide both comfort and a call to action. Efforts to repair the world in honor of the departed may not lessen our grief in the wake of such tragedies, but they do unite the living in accomplishing important and rewarding work.

Whenever we engage in such repair, we activate the spirit of Lincoln's Gettysburg speech. He was wrong when he said "the world will little note nor long remember what we say here," and I suspect he is chuckling somewhere at all the attention his ten sentences now receive. What would really give him pleasure, however, is that his flop of a speech continues to inspire both "increased devotion" and action to further the cause of human liberty.

We often feel that our children don't listen to us, our bosses don't appreciate us, and our most heartfelt endeavors meet with crushing failure. Let us be inspired by Lincoln to understand that our greatest successes are not always immediately apparent. If you've experienced a significant disappointment that eventually turned positive, please share it in the comments below.

May we all merit to see our biggest "flops" turn into our most meaningful accomplishments.

Salvador Litvak wrote and directed Saving Lincoln, the true story of President Lincoln and his closest friend, Ward Hill Lamon. All of the film's sets and locations were created from actual Civil War photographs. Learn more at SavingLincoln.com. Litvak also writes as the Accidental Talmudist for the Jewish Journal.