In thrilling spectacles of political performance, Kendrick Lamar and Beyoncé showed solidarity with the #BlackLivesMatter movement and the Black Panther Party for Self Defense before audiences of millions at the Grammy awards and the Super Bowl. But how many of those millions realized that these two brilliantly orchestrated displays of militant artistry exemplify a form of protest first staged by Sixties radicals: the zap action?

Zaps are highly theatrical, non-violent displays of civil disobedience that typically involve skits, costumes, and props. Infusing social protest with guerrilla theater, zaps are symbolic actions designed to shock spectators and attract media attention. Favoring confrontational tactics over boycotts and sit-ins, zaps, as the name suggests, deliver a jolt in the form of a strike or attack. The goal is to expose injustice and catalyze public responses to current events.

By any measure, that's what Lamar and Beyoncé accomplished.

Queen Bey held court at the Super Bowl half-time show, urging people to join the cause, to "get in formation." Leading an army of Afro-appointed dancers in black berets through a series of choreographed maneuvers punctuated by the pumping of raised fists, Beyoncé celebrated the beauty of black resistance to the beat of her freshly dropped single.

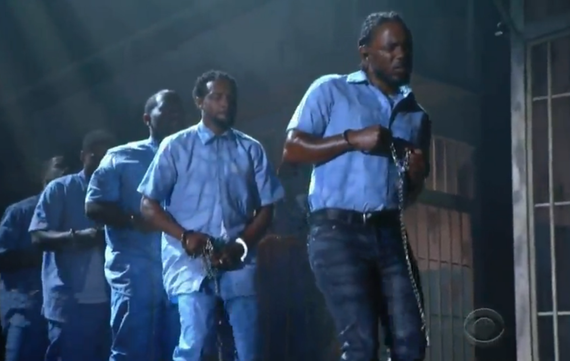

Compton rapper Lamar took the stage at the Grammy Awards in a radically different formation, one black men in this country have known all too well, a chain gang. Shuffling along in lock step with a line of shackled prisoners, Lamar put America on notice with "The Blacker the Berry," accompanied by his band caged inside cells. A blistering indictment of police brutality and the prison industrial complex, the song ends with a jailbreak and the transition to "Alright," a black power anthem, set against the backdrop of a raging fire.

Zap actions were popularized by the Yippies! -- a group of anarchists associated with the anti-war and free speech movements. Influenced by the Black Panthers, the Yippies! created a counter culture with food co-ops, free clinics, underground newspapers and exemption from the draft. Their mission and style, however, seem at first glance more Beyoncé than Lamar. The Yippies! goal was to make the revolution fun by any means necessary. They promoted "a politics of ecstasy" and staged satirical zaps that made a mockery of authority, including nominating a swine, named Pigasus the Immortal, for President at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago in 1968. When riots broke out, several Yippies!, including co-founders Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin, were arrested along with Black Panther founding chairman Bobby Seale.

The Chicago Eight, as the defendants were known, became the Chicago Seven when the judge severed Seale's case, after ordering the Panther bound and gagged for calling him a "pig," "honky" and "racist" during the proceedings. In response, Hoffman and Rubin staged several zaps to draw attention to state-sponsored violence and the discriminatory treatment of black revolutionaries. One day, they arrived dressed in judicial robes. When the judge ordered them to remove their costumes, the Yippies! did so willingly, revealing Chicago police uniforms underneath. Heroes to some, the Yippies!'s aroused ire and condemnation from serious-minded leftists who viewed them as frivolous and self serving.

Similar charges of superficiality have been levied against Beyoncé's "Formation" zap. As the scantily clad diva paraded across the field, dueled with Bruno Mars in a mock dance battle, and strutted down the runway with Chris Martin, social media exploded with debates about whether the half-time show was an homage to or a parody of the Black Panthers. For the Panthers, getting into formation meant lining up to serve meals to the homeless and performing paramilitary drills in preparation for the coming revolution. "We gon' slay" had nothing to do with killing it on the dance floor. It meant taking up arms in defense against police brutality and being committed to liberation by any means necessary. For many, Lamar's Grammy performance more accurately reflects the seriousness of the cause (President Obama didn't tweet congratulations to Bey). But, is it a question of tone, or is it a question of people's discomfort with Beyoncé honoring Panther women in a celebratory performance of black female sexuality?

The Black Panther Party constituted the vanguard of revolutionary activism. They viewed black liberation as part of a global struggle against oppression, which eventually grew to include both sexism and homophobia. Co-founder Huey Newton issued a formal statement embracing feminism and gay liberation. Even as females came to constitute the majority of the party's membership, the organization retained its aggressive vision of manhood and patriarchal division of labor, which reinforced male privilege and stereotypical attitudes about sex and sexuality.

These problems plagued most militant political organizations of the era, including the Yippies!. Fed up with what she called their "ejaculatory tactics" and "clownish proto-anarchism," Robin Morgan left the Yippies! to found New York Radical Women and later WITCH (Women's International Terrorist Conspiracy from Hell), groups committed to staging shocking theatrical spectacles in the service of radical feminism. Famous feminist zaps include casting a hex on Wall Street, staging a mass "unwedding" ceremony at the first Bridal Fair at Madison Square Garden, and crowning a sheep at the Miss America Pageant.

As Omise'eke Natasha Tinsley and Caitlin O'Neill have noted, "Beyoncé's performance celebrates black Southern conjure women and the magic they wield." Her "Formation" zap both honors the legacy of the Black Panthers and offers a satirical jab at male chauvinism. Beyoncé's stage was the pinnacle of male power and privilege, the Super Bowl, and she let the world know that she is a player, a star player who outperforms most men in the entertainment game, including professional athletes. The spell she cast is so powerful that we cannot stop talking about her. She hijacked all major media outlets and launched boycotts by those opposed to her insistence that Black Lives Matter, that Black Women's Lives Matter, that Black Queer and Trans Lives Matter - all while raising the profile and sales of Red Lobster with just a mention.

Beyoncé's biggest critique involves her unabashed celebration of capitalism, which the Black Panthers denounced as an economic system that is rooted in slavery and which must be overthrown in order to achieve liberation. In Seize the Time, Bobby Seale calls black capitalists exploiters and oppressors. Beyoncé graciously begs to differ, claiming the "best revenge is your paper."

Beyoncé is a philanthropist committed to sharing the wealth, donating millions to support the Flint Child Health and Development Fund and create housing for low-income and homeless populations in Houston. She and husband Jay-Z have paid to bail out protesters in Baltimore and Ferguson. They have also given $1.5 million to social justice organizations, including the #BlackLivesMatter movement. Co-founder Alicia Garza has written that Beyoncé's "Formation" is "complicated - and so is the movement itself." The issue of Beyoncé's celebrity, notes Garza, and her "celebration of capitalism -- an economic system that is largely killing black people, even if some black people, like her, achieve success within it" have been "a source of important critique."

In the 1970s, Yippie Jerry Rubin became a born-again capitalist, converting from a Yippie! into a Yuppie. After failing to achieve "the radical dream of transforming the system from outside," this reformed Marxist took a job on Wall Street and became an early investor in Apple Computer, which earned him millions. "Wealth creation is the real American revolution," Rubin came to believe, and "the individual who signs the check has the ultimate power." Though he remained committed to many of his core values and to creating a more equitable society, Rubin insisted that he was more effective "wearing a suit and tie" than he was "dancing outside the walls of power." Beyoncé has danced her way inside the walls of power. "I dream it," she sings, "I work hard, I grind 'til I own it." Is sharing this considerable wealth enough to transform social relations, or is it better to tear down those walls, eradicate that capitalist formation? Whether political performance in its 2016 incarnation stops at recognition or leads to systemic change is still a question.

(Sara Warner is an Associate Professor in the Department of Performing and Media Arts at Cornell and a 2016 Public Voices Fellow at the Op-Ed Project. She is the author of Acts of Gaiety: LGBT Performance and the Politics of Pleasure. @FieryOptimist)