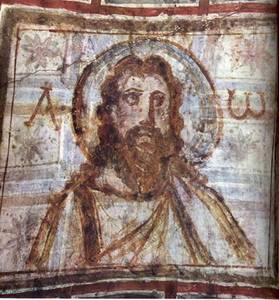

Jesus didn't go to church. Scholars of early Christianity have long known this. The earliest gospels that recount his life never describe him attending church. In fact, churches didn't exist in his lifetime; rather, churches are social institutions that emerged among his followers after his death. Jesus himself appears to have gone to local synagogues (as in Matthew 4:23, 9:35; Mark 1:21, 6:2; Luke 4:16), just like other Jewish people of his day. In any case, what many American Christians now think of as "going to church"--people getting in their car on a Sunday morning, driving to a building that is specially designated for Christian ritual worship, engaging in a series of formal activities for a couple hours, and then returning home--didn't exist in the ancient world anyway. In the first couple generations after Jesus' death, not only were most groups of his followers small in number, but they also did not have the resources to purchase and dedicate special buildings for their meetings. The Greek term that is translated in the New Testament as "church" (ekklēsia) simply means "assembly"--and many other people besides the followers of Jesus used the term to describe different groups coming together, in all sorts of places, for meetings.

So if early groups of Jesus followers weren't going to church in the way that many modern Christians understand it (and if they didn't have strong ties to Jewish communities, they probably weren't going to synagogues either), then what were they up to? About a generation after the death of Jesus, Paul, the author of numerous letters in the New Testament, writes 1 Corinthians to people who come together in small groups to share meals and other activities. It is reasonable to assume that many of the groups to which he writes engaged in similar activities, even though they aren't discussed in as great detail as 1 Corinthians (in fact, 1 Corinthians dwells on these features because there seem to be problems with how they are being carried out). There is much historians simply do not know about these meetings, though. Where did these people meet? Who paid for their meals? Who was in charge of their various activities, which in the Corinthians case included prophesying, speaking in tongues, singing hymns, perhaps some kind of teaching and interpreting, and eating meals (1 Corinthians 14:26)?

One way to envision these meetings is to suppose that they took place in people's private homes. This was no doubt a venue for some. But we still don't know who exactly hosted them, how they were funded, who was in charge, and where they might go if the group became too big for a private home. What we'd really like to do is to compare the activities of these early Jesus groups with other ancient people who met for similar purposes: to share a common meal, to carry out devotional activities for their deity, and to enjoy the company of a broader community. One persuasive historical analogy that scholars of Christian Origins are starting to take more seriously is that of ancient voluntary associations. Greeks, Romans, Egyptians, and many other ancient peoples frequently established voluntary associations that people could join in order to socialize with other people who shared a common occupation, deity, or regional or ethnic affiliation. What's more, these associations have left an enormous amount of written evidence for the ways that their groups were organized, how they raised money for their activities, and where and when they would meet. This evidence is preserved in inscriptions on buildings, in papyrological documents, and on the facades of statues, among other locations. By comparing evidence from these groups to the early Jesus groups (especially those lying behind Paul's letters), we can generate new insights about meetings among Jesus' followers before the formal institutions of churches arose.

Let's consider one example. A column from an ancient building preserves an extensive set of rules and regulations for members of a group devoted to the Greco-Roman god Bacchos. The group has various officers, such as a priest, vice-priest, president, and treasurer; these positions are chosen through nominations or votes. They have a series of regulations regarding who can become a member and what they must contribute to the group as part of their membership; they require membership fees which help fund the banquets and other group activities. Much of the inscription describes activities at banquets and other events, and in particular, what to do when the group becomes disorderly. Fascinatingly, this group not only requires the payment of fines if some rules are broken, but it also speaks of "bouncers" who are tasked with maintaining order at meetings. Despite these rather ordinary details, the purpose of the group is primarily cultic; they meet monthly to honor their god and also attend annual festivals and other relevant feasts.

So by keeping this evidence in mind, we can turn back to the groups to which Paul was writing and ask new questions. Do Paul's groups have "officers"? How were they appointed? How did the group decide to admit new members? Was there an initiation process in addition to the oft-mentioned baptism? Did members have to pay an entry fee (we know that many already contributed to the collection for "the saints" [literally "the holy ones"] in Jerusalem)? How did the group decide the manner in which a meeting would proceed? Who would speak in tongues and who would interpret? Should hymns be sung at the beginning or end of the meeting, or somewhere in the middle? What were the protocols when things got too boisterous and rowdy? Did members expect someone to maintain order in the same way that the Bacchic bouncers did?

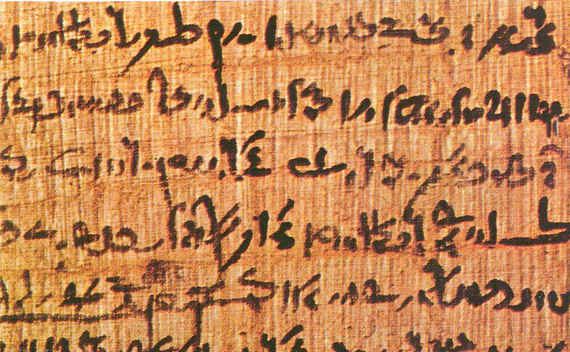

We won't always be able to answer these questions, due to the limited nature of our evidence for these very early Jesus groups. Nevertheless, by exploring analogous voluntary associations, we can think about other things that might be going on that might not be explicitly mentioned in the New Testament. And sometimes, this comparison can even cause us to rethink some of our data. To offer just one example, my colleague Richard Last and I have examined the accounting practices of one association that are recorded in P.Tebt. III/2 894 (a papyrus found in Tebtynis, Egypt that is dated to the second century BCE). This group is meticulous in recording the contributions of each member, the expenditures for each meeting, and the outstanding fees and fines that members owe. By comparison, though Paul never unambiguously describes his groups' accounting practices, something similar may be taking place so that he can keep track of donations. He evidently gives his groups directions for taking up the collection (1 Corinthians 16:1-2), and in some cases, singles out people who have only been contributing for a short time (2 Corinthians 8:8-15). Last and I even suggest that some of the Galatian groups failed to make the required contributions, because Paul does not mention them in Romans 15:25-26, a passage where he reviews the source of the collection that he is taking to Jerusalem. Paul must have had a way of keeping track of these diverse contributions--could he or his groups have kept detailed written records akin to those found in P.Tebt. III/2 894?

These sorts of comparisons do not imply that the later followers of Jesus were exactly the same as these other ancient associations. Naturally, there were very significant differences. For instance, whereas many associations were limited to specific regions (although there were some connections among cities), Paul's letters suggest that his groups were highly aware of their translocal (meaning networks of social relations that extend beyond the local region) connections. The Thessalonian group, for instance, may have been a small group of Jesus followers in the city of Thessalonica, but they likely imagined themselves as part of a much larger network of believers, with its original hub in Judea. This translocal identity is reinforced by Paul's request for his groups to collect money and send it back to "the saints" in Jerusalem. Despite such differences, the comparison to other associations does help us understand what ancient people might have thought they were doing when they got involved with a group devoted to Jesus. They may have expected the Jesus groups to look and behave just like other associations that existed all over the Mediterranean world. Indeed, the earliest "churches" may have started out looking rather ordinary to most people in the Roman Empire.