The Syrian Desert is cold in December. I knew from similar country in Southern California and Nevada it would be like this. But I wasn't prepared for the extent of it, or the duration. Daytime warms up, probably into the 60s, but nights dip to (what feels like) sub-freezing temperatures. Clear, starry and cold, with vapor-trail breath and wind-stung hands.

I've spent the last ten days on a massive airbase called Al Asad (The Lion, in Arabic). I was there to meet the Colonel in charge of the Marine Corps' Fifth Regiment (its most decorated). I interviewed him several times and watched him engage an Iraqi counterpart (the General in charge of the 28th Division) at a base called Al Qaim, on the Syrian border. The trip back to the COP (Combat Outpost) at Haditha, where I've been for two months, was a two-hour hike by Humvee--my first ride in the workhorse of the American military.

Most of the missions I've been on have been in MRAPs--massive six-wheeled monstrosities designed to defeat IEDs (Improvised Explosive Device). The Humvee is a bit chilly (a turret gunner stands through a gaping hole in the roof) but otherwise comfortable. A box containing electronic gear and communications equipment separates the driver from the navigator, who has an LED display in front of him with highly detailed and multi-colored, topographical GPS maps. I'm in the rear-passenger seat and to my left are the booted feet of the turret gunner. Beyond them, in the other seat is a shiny-headed, middle age NCO who's getting transport to Haditha to grade its kitchen workers. I'm secretly in awe of the guy as he's achieved a Zen-like state in which he looks simultaneously bored and pissed off. He doesn't say a word the whole trip.

The Humvee has a kick-ass sound system and the Marines are jamming Queens of the Stone Age (as well as a litany of heavy metal titles that run far wide of my ken). It's easy to fall into reverie here, losing myself in memories of long-ago late night road trips in the hulking night of the open and endless American road. In a way, I figure, strangely enough, we're some bastardized new-century versions of Sal Paradise and Dean Moriarty, carving out our own Finnish (heavily armed) adventure, the venerable Euphrates our Mississippi and the darkness of the desert night a renegade confederate and a willing abettor. It's easy to forget, in the ease and comfort of this decibel-blaring steel-skinned cocoon, that Anbar has been kinetic the past two days and there are likely foreign fighters hidden in some of the wadis we're passing (dry river beds), that would as soon kill us as piss on us.

Outside, I trace the dark path of the river, below a blanket of blinking stars. The driver--a body armored man with the face of a teenage doughboy stepped out of an after-school special--fires another grit to life and the sweet, caramelized aroma of American tobacco fills the pen. Domiciles glide across a screen of glass four-inches thick, with beleaguered cars of European intent sitting on the roadside next to them, corralled for the night, waiting for daylight and human peregrinations. Sometimes it feels as if we could be in northern Florida, or maybe even southern Ohio, following backcountry tributaries through the umbrageous boondocks--searching for beer and sniffing out adventure.

Then we pass indigenous low-lying, stone huts put together with Jenga-like determination and stuck fast with bitumen, sweat, and a gob of spit or two--and then onto vast vistas of nothingness, as empty as the space-time continuum--and it seems we've landed on the other side of the Utah moon. Forty minutes into the trip we get stuck behind a civilian convoy of lorries and the pace drops to a crawl--a sign of the times. Just a year previous, Marines wouldn't have considered stopping for traffic--and making themselves ambush-bait and a stationary five-ton target for RPG-training insurgents. Doughboy and Navigator--smoking cigarettes like it's cool, and working through a small cache of energy drinks--are pissed that the lead vehicle in our convoy (containing the mission commander) doesn't have the balls to pass the obstruction.

"That's why I hate riding with Bennett," Doughboy yells above the music, "he's a godamned pussy."

Navigator contemplates the last eighth-inch of burnable paper on his grit, sucks the cherry right up to his lips, and exhales a cloud of white smoke onto the rear of the fortified windshield.

"You knew this shit was gonna happen," he yells. "Now we're gonna be here two f---ing hours."

We finally clear the obstruction, and then, half an hour later, Bennett's Humvee, the lead in our three-vehicle convoy, comes to a stop in the middle of the highway; Doughboy follows suit, two hundred yards behind. Navigator turns his head and says something unintelligible; I hear only thumping bass. The others dismount and I struggle to push open the ungainly door. Climbing out, I adjust my Kevlar helmet and the steel plates in my vest, wondering why we're sitting stationary in the middle of a perfectly good highway. Then the pissing commences. Four of us, now five, relieving our bladders about an asphalt thoroughfare constructed in the time of Saddam (during the Second Coming of Babel), as another convoy of mammoth MRAPs, five meters high and radiating halogen, races past in the frosty, alien night.

After the trucks, there is nothing, and in my mind a vision of Camille Paglia flutters into focus ... where rock 'n' roll goes, democracy follows ... and the stereo is rollicking--the high-tech million-dollar communications box pumping out a punishing tempo of head banging angst--and I realize we're backlit like flies on a bug zapper by the baleful and bristling vehicle behind us. It's then I look up to see the turret gunner, standing on the hood of the Humvee, pissing onto the blank and desolate highway that stretches into the darkness before us like an intimation of fate. This is my snapshot, the one I will file with this chapter of the journey, next to pictures of my sister's kids and old girlfriends: the climactic throes of the American Empire, empty ejaculations in the Arabian night ... four swinging dicks in body armor, camouflage clothes and fifty-caliber, fuck-you stares, nicotine smiles and enough testosterone to blot out the sun, amped on life and ready for games of chance with Gods they don't yet know they'll never understand.

An hour later and we pull into the COP at Haditha. The Sergeant charged with my well being leaves me to my own devices and I tramp off, penguin-like--heavily loaded with a stout duffel, body armor, a backpack, and a bedding roll--to hooch number 13. I've only been at this COP two months, but already it feels strangely like home. Before the trip to Al Asad, I'd been bunking with the Second Lieutenants that are in charge of the three platoons in India Company--I find that my spot's been appropriated by Second Lieutenant Bass, whose fourth platoon has recently relocated from the Dam near Haqlania (the Americans are abandoning outposts everywhere, downsizing and handing patrolling responsibilities over to the Iraqi Army).

I've been bumped over to hooch 12, with Sergeants Meza and Warfield, where I have a mattress on the floor and access to a desk--everything I need in the world. The hooch is a big wooden box, about half the size of the last living room I had in San Diego, and though the Marines generally stay eight to a unit, officers and staff sergeants (and myself, by extension) enjoy the spacious privileges of rank. The hooch is kept warm with two heaters (that double as AC units in the summer) and is delightfully dark--a veritable grotto--when the lights go out.

In Full Metal Jacket the Marines rose with the sun, startled into consciousness at the traumatic bequest of garbage pail lids. But this is a war zone and the Marines I know (particularly the officers) don't sleep according to daylight schedules; they sleep when they can. When there aren't missions, or watch-o (six tedious hours of sitting in the COC--Command Operations Center--waiting for important calls or kinetic activity), they're free to do as they please. Sleeping in till eleven or twelve in the afternoon is common. Then again, staying up from midnight till six a.m. for watch, or six till twelve in the afternoon, is a ritual carried out three times a week. On the bad days, that midnight to six a.m. stretch is followed by a seven o'clock mission into town--no sleep till late afternoon.

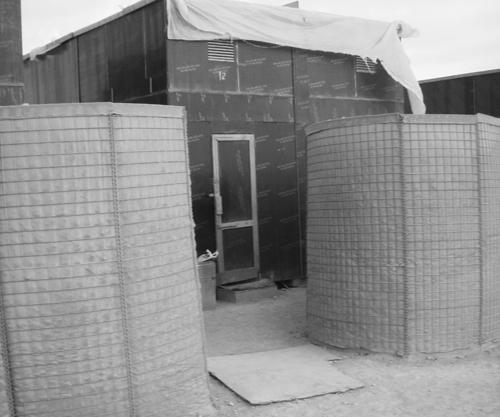

When they're not on a mission--any event that takes them outside the COP--or pulling post (guard duty for enlisted men) the Marines generally lounge in their hooches. When they leave, they go heavily armed, with at least one four-man fire-squad for security. The entire COP is about a half-mile in circumference and composed of four parallel dirt roads lined with hooches (as well as a cafeteria, the COC, a gym, and hundreds of Hesco units).

Hescos are large wire boxes (three feet high or ten feet) that are lined with felt and filled with dirt. There's nothing like a wall of earth, four-feet thick, to protect against gunshots and bomb blasts. The rest of the camp is ringed with 12-foot monolithic concrete slabs called T-walls, and much of it is lined with gravel. The place is like a rustic squatters camp in the hinterlands of southeastern California--a living tribute to Leonard Knight at Salvation Monument, and a bellicose doppelganger of Slab City.

The COP has showers--with hot water--but no indoor privy. Each of the Cardinal corners of camp has a set of Port-a-Pots. I've developed PTSD from using those inhospitable dens of ignominy on cold Mesopotamian nights. There's nothing more mentally grating than having to leave the warmth of a perfectly good hooch to sit your bare bottom on a freezing disk of plastic and smell the unsavory bouquet of the evacuated dinners of 300 Marines.

There's no drinking on the COP, but tobacco (cigarettes and chew) is consumed by the barrel. The Marines complain about the food (pre-packaged potatoes, meat products, ravioli, etc.) but it's always hot and, though it's admittedly institutional, I like it. The sparse chow hall is open 24-hours and it has a big screen TV, which perpetually blasts the American Forces Network--mostly football and movies. Most distressing (and as contrary to popular perception as the sleeping schedules here) is the lack of hot java. Some of the officers have their own coffee pots, but the chow hall has a lame cooler of the stuff that sits (losing heat rapidly) throughout the day--and that's just on the days it's replenished at all. The horror, the horror, quoth Conrad.

I've improvised my own brew-kit, with a plastic bottle--but I still need hot water. Even the water urn has disappeared from the cafeteria, so I'm forced to boil mine in the microwave. The great irony is that I'll almost certainly not be killed by an insurgent in this largely peaceful place, but the cancer generated by that carcinogen-spewing microwave will probably fell me before my return flight to the states (my only hope is that the dizzying proliferation of the lawsuit lifestyle and its collision with the holy decrees of Political Correctness will poison this place, too, and allow me to sue the insurgents--just reparation--for forcing my trek here in the first place).

Another great misconception is that Anbar--once the capital of the insurgency--is still a hotbed of violence and contention (the U.S. media is lagging by more than six months re its comprehension of the hard realities in western Iraq). The 3/7 Marines I'm embedded with have been here since August, and until mid-December, they'd not been shot at or fired on anyone. Things have been more kinetic lately (two incidents in mid December), but it's not worth mentioning when compared with the hostility festering in the area just a couple of years ago (in 2007, this COP was taking mortar rounds on a regular basis). The general thinking is that things have heated up recently because of upcoming elections (votes for provincial seats will happen at the end of January 2009), and that they'll settle down again afterwards.

"I've run security for elections in Central America, the Balkans, and Iraq," a 12-year Corps vet tells me, "and in every place violence spikes before elections. Don't ask me why, it's just part of democracy, I guess."

Most of the Iraqi civilians I've talked with want the Americans around--they're concerned the Coalition is pulling out too fast. The thinking seems to be different in Baghdad and when I ask the locals why that is, they say the capital is eaten up with Iranian influence (and indeed, when Muqtada Al-Sadr flees, he goes to Iran ... and the ties between Persia and the current Iraqi prime minister, Nuri al-Maliki, are no secret). With the recently signed SOFA Accord, the Coalition has three more years, in country. I don't think anybody really expects that the U.S. won't have a footprint here four years from now (there will still be Americans at Al Asad), but the signs are already clear--power's being transferred all over Anbar Province.

The question is, will three years be enough time for the ethereal Western notion of democracy to germinate in this tribal land, where family grudges are passed from father to son and where most of the notable players in the neighborhood (Iran and Syria) are hostile at best and popularly believed to be keen on taking over. The people here who give outward signs of knowing what's going on--those that are also sane--tell me that to guarantee democracy, the U.S. needs its military in Iraq for an entire generation--enough time for the old ways (autocratic heavy-handed rule, archaic vindications and inherent corruption) to die. Five- to seven-years would give it a good chance. Three years is a crapshoot, they say.

I ask Doughboy about that timetable and he inhales deeply on a cigarette.

"F'wee leave here too early, it'll mean all them boys died, died for nothin'," he says. "And we'll be coming back, two years later, an' doing the job all over again."

For more observations from Iraq, go to http://sdliddick1.shutterfly.com/