The recent Opening Night performance of John Neumeier's Nijinsky at San Francisco's War Memorial Opera House proved to be a climactic experience. It marked the Northern California Premiere of the work which had its World Premiere in 2000 with the Hamburg Ballet -- where John has been the Artistic Director and Chief Choreographer since 1973. Performed by the artists of the Hamburg Ballet, and with Simon Hewett conducting the orchestra of San Francisco Ballet, the production is epic in content and colossal in artistic output.

Vaslaw Nijinsky has long been recognized as the greatest Classical dancer of the 20th Century. His relationship with impresario Sergei Diaghilev and the Ballets Russes is the stuff of legend. For choreographer John Neumeier, the life and career of Vaslaw Nijinsky has been an enduring source of illumination and an unfailing point of inspiration. A great portion of that love and energy was channeled into collecting a vast array of literature, art and memorabilia related to the dancer and the Ballets Russes. In 2006, the Foundation John Neumeier was created to secure this unique collection as well as materials extending from his own oeuvre as a dancer, choreographer and director.

As someone who gathers film memorabilia from MGM's golden age, I understand the heart of the collector/historian. There is always a degree of covetousness involved, along with occasional bouts of heartbreak. For example, in John's 2000 essay, A Choreographer and Nijinsky: Facets of a Fascination, John describes his disappointment in not acquiring Nijinsky's diary when it came up for sale in the early '90s. The essay is a confession on the art of collecting and pre-dates the establishment of his Foundation. During our recent interview, he described a group of illustrations acquired at a Christie's auction.

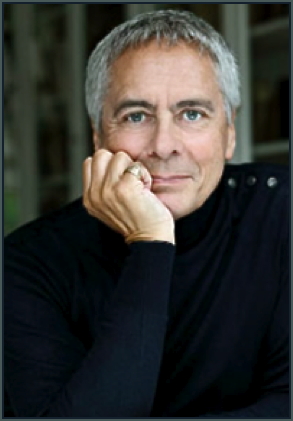

John Neumeier. Courtesy of The Hamburg Ballet

John Neumeier:

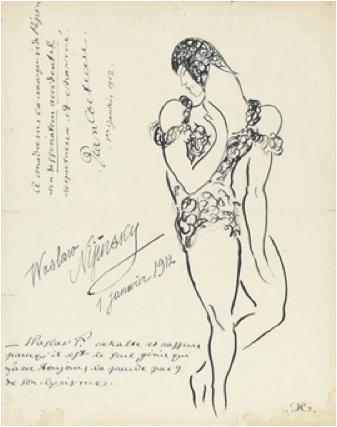

Sometimes you're so surprised when an item suddenly comes up. Recently there were some fantastic drawings that I've known by Cocteau of Nijinsky. The drawing is dated Jan. 1, 1912 and was a gift to Lady Ripon. It's signed with a long inscription by Cocteau and a beautiful signature by Nijinsky. It was sold together with two other drawings of which they said the authorship was not clear. They are the parodistic drawings of Diaghilev as the Maiden from the Spirit of the Rose, and boxed as The Rose. They said, "We don't know who the artist is." But everybody knows who the artist is, because they've been published. This was the most tense moment, I think -- bidding for that object. I knew that the Victoria and Albert Museum knew about it. It was really a question of who was going to keep up. If the Russians had become interested -- which is the deadly thing today, because they have unlimited funds -- I wouldn't have got it. It's an amazing drawing. There's always this moment when something comes up and you know that its home belongs with you. You just know it.

By Jean Cocteau (1889-1963). Portrait of Nijinsky in The Specter of the Rose. Courtesy of John Neumeier Dance Collection

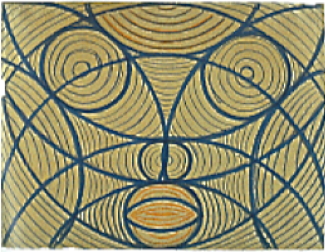

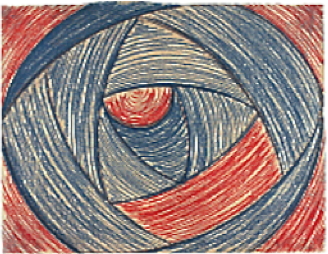

Currently, his Foundation's collection has been tapped by the Museum of Modern Art in New York for the exhibition, Inventing Abstraction, 1910-1925, which runs through Apr. 15. Turns out, between 1918 and 1919 Nijinsky created a large number of fine abstract illustrations. Five of them are included in the exhibit which features among others the work of Vasily Kandinsky, Robert Delaunay and Marcel Duchamp.

By Vaslaw Nijinsky. Untitled (Arcs and Segments- Lines), 1918-19. Crayon and pencil on paper. 11 x 14 3-16 ins. (28 x 36 cm). Courtesy of Foundation John Neumeier

John Neumeier:

I was so pleased that they asked for five drawings of Nijinsky. Along with the greatest painters between 1910 and 1925, who invented this new form of art which is very well catalogued and described, we have Nijinsky the painter as part of this movement. So, since my article you mention, I've gone into yet another phase, another fascination with this man who had so many layers as an artist and as a humanitarian. Nijinsky's drawings are abstract, not realistic or figurative. It is design, very much involved with the circle. This was a fixation of Nijinsky. We know from his diary that he had envisioned a circular stage. He believed the circle was the most perfect form that the human being could create. If you see the drawings isolated you might say it's just the drawing or painting of a mad person. But when you see a whole lot of them, you realize there was a system and a sense of experimenting and discovery within them. You see how one design idea led to another. There is a unifying image, the eye. If you were to see them in my house, I hang them provocatively together: how people saw Nijinsky and how Nijinsky saw the world. Many images of him are sort-of late Art Deco. But what he saw was something that was really going into the future, just as his choreography was -- at least, the concept of his choreography.

By Vaslaw Nijinsky. Untitled (Arcs and Segments- Planes), 1918-19. Wax and colored pencil on paper. 11 x 14 9-16 ins. (28 x 37 cm). Courtesy of Foundation John Neumeier

In the course of Neumeier's ballet, multiple dancers representing Nijinsky in his most memorable roles weave in and out of various scenes. The splendid costumes, based on original sketches, let us glimpse into the fantastic world that was the Ballets Russes and of its young composers -- including Stravinsky, Debussy, and Prokofiev -- whose music was wildly inventive and provocative, even to the point of inciting riots during a performance. Each dancer exudes the erotic tension and daring physicality of the Nijinsky so familiar to us through a smattering of photographs that survive. It is an amazing theatrical device that enriches the ballet's narrative and exalts the mystery of the man. It also points to the creative power of John Neumeier and the depth of his insight and spiritual kinship with the artist. But how is that gnosis imparted to and so consistently realized among a group of "Nijinskys," especially those coming into the ballet for the first time?

Alexandre Riabko (Nijinsky) and Carsten Jung (Diaghilev) in Neumeier's Nijinsky. Photo, Erik Tomasson

John Neumeier:

The important thing is to not say too much in the beginning. That is basically my theory. The ballet was created in 2000. After thirteen years, I'm finally giving it to one company -- the National Ballet of Canada. When we started working on it, I did give them a little bit of a lecture about Nijinsky and the concept of the ballet as I thought it should be. Then I think it's important to teach the language of the piece. It's an emotional language. It's not shown in a kind of abstract way, but in a very emotional way. First of all, it's important to watch that person, because we are not trying to fool the public -- that Nijinsky has risen from the dead and is now on the stage. The types of people who have done the part are very different. I think in Art we make a parallel reality. It's not a photographic reality. I would prefer to give a broad informational background to what we are doing and, as we move through it, give details which help the dancer find his own way of doing it. I think it's important that they be people who can give me parallel emotional pictures and parallel emotional combinations between Romola, Diaghilev and Nijinsky -- all the colors -- because he was so many things to so many people.

I think his marriage to Romola is the greatest mystery around him. He was bisexual from the beginning. I do not think that the relationship with Diaghilev was one sided, that Diaghilev seduced him. It was a mutual, also physical situation between them. We know certain things from his diary, including his relations with prostitutes in Paris. At a certain point he just wanted to have this woman. He didn't think it would have the consequences it did. There is a very interesting letter he wrote to Stravinksky, which is in Switzerland, in which he is quite confused at the reaction of Diaghilev to his marriage. I believe he thought that the two things could somehow continue at the same time. What is interesting for me -- and you will see this in the ballet -- is that I don't judge anyone in it. I won't call it "scholarship," but in the Nijinsky fanaticism there are generally two camps. First, Diaghilev is the Devil. He seduced Nijinsky and that his madness was due to the relationship. Then there are those who consider his wife the Villainess. She is the one who took him away from his homosexual relationship and, therefore, brought on his madness. I don't think either one of them is right. Even the situation of his being released from the Ballets Russes is quite complicated. He was not released immediately upon his marriage. He was released later during the South American tour when he failed to perform at an event where there was no understudy for him at that moment. He knew his wife was pregnant. She convinced him to stay with her that evening and, therefore, he was released. As the director of a company, I can well understand that.

Thiago Bordin (the Faun) and Hélène Bouchet (Romola Nijinsky). Photo, Erik Tomasson

The score of Part I is comprised of music by Frédéric Chopin, Robert Schumann, Dmitri Shostakovich and dominated by three movements from Nicolaj Rimskij-Korsakov's Scheherazade. Part II employs Shostakovich's Symphony No. 11 in its entirety. Though a daunting task, even across the street at Davies Symphony Hall, the music is a surprisingly excellent match for the closing episodes which illustrate Nijinsky's encroaching madness, the horrors of World War I, the death of his brother, Romola's infidelity and the uproar that occurred around his innovative ballet of 1913, The Rite of Spring. Yes, it feels long and most certainly it is a tour de force for the artists. But the journey is magnificent.

John Neumeier:

I think the act of creation is an intuitive act. The act of preparation is a rational act -- you intellectually try to understand things through your own emotional structure. But when you begin to choreograph, you don't "check" yourself. Things flow as they have to flow. This has to do with the music you've chosen, how that music is propelling you to go in a certain direction. So, I didn't control myself -- in the moment of creation. When something is finished -- and in a sense, you can say that it's never finished -- then you can control. Every time I watch the performance I change something. I feel that a ballet is a living art and it has to stay living so long as the choreographer lives. I believe he must still constantly check his work -- if it still feels honest and if he is still moved by it. Or if he thinks 'it's okay, it's just the status' -- this I would never want to feel about any work of mine.