On this Veterans Day, my family will mark the fifth anniversary of my father's death. My father, Gerald Gitell, a Special Forces combat officer in Vietnam, died the night of Veterans Day. By the last decade of his life, he came to realize that he suffered from what is now referred to as Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, and on that very last night of his life, he watched an HBO documentary on the affliction narrated by James Gandolfini called "Wartorn."

Today, awareness and understanding of PTSD informs the public's view of veterans of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars -- even with the gaps in treatment and service that exist. Public service announcements talking directly to veterans about PTSD and its modern counterpart, traumatic brain injury, are commonplace. Philanthropic and government efforts target PTSD alongside the grievous physical injuries today's soldiers and marines have brought home with them from war.

Such was not the case for much of the 1970s and 1980s, the period during which my father struggled with his wartime demons. He had to survive in a world with minimal compassion or understanding toward his problems. In fact, the unique circumstances of his background and situation probably made everything worse.

First off, he was a Green Beret, a member of the elite band of soldiers selected by President Kennedy to spearhead the war in Vietnam and other efforts in the proxy wars against Communism in the post-Eisenhower Cold War. To earn his beret, my father had to volunteer three times and undergo a harrowing series of tests and training -- through most of which, to my understanding, he thrived. The Special Forces motto, then, as now, is "De Oppresso Liber," a Latin phrase which means to free the oppressed. He believed it. He lived it.

While at Fort Bragg, which President Kennedy had visited only three years prior to my father's service there, he met a fellow Green Beret with an interest in music, Staff Sgt. Barry Sadler. Shortly after the two met -- while engaging in war games on the fort grounds -- Sadler asked my dad, who had a communications degree from Boston University and was serving as the Public Information Officer of the unit, for help with his song, "The Ballad of the Green Berets." My father agreed and arranged for Sadler to record a demo of the song, earning it the status as the official song of Special Forces. He then sent copies of the tape and a pitch letter out to record companies.

Ultimately, one of these pitch letters struck gold. A company named Music, Music, Music, gave Sadler a publishing contract for the song, and the artist designated 25 percent of these fees to my dad. He wasn't aware of this stroke of luck when it happened. He was a lone American leading CIDG local forces in the canal region of South Vietnam. Soon after his return home from Vietnam, thanks in part to an appearance on "The Ed Sullivan Show," "The Ballad" was the number one song in the nation, a position it held for five weeks. Sadler's standing that year was equaled only by the Beatles.

All that was before I was born. My father and mother lived together less than five years. The small house we inhabited was less than a quarter mile from the beach. On weekends, our whole extended family, including my grandparents who owned our house, decamped to the beach. Everyone, that is, except my father. I could come home from the beach on a brilliant beach day and find him huddled on the couch with a pillow quietly sipping scotch and watching war or cowboy movies -- Barry Sadler's face on an album propped on a record player looming over the scene. The juxtaposition was raw. "The Ballad" remained a source of pride for him until the end of his life, but its flash of success compounded my father's pain.

My father's frequent bouts of unemployment, chronic drinking and personal quirks elicited a straightforward reaction from my mother. She threw him out -- still an uncommon thing among her middle class Jewish social set in the mid-1970s. With no real awareness of PTSD, she approached his behavior with a mix of puzzlement and hostility; after all, how could a Boston University-educated man, brilliant in conversation, with the success of a number one song behind him, have such a hard time coping? Ultimately, she decided life would be more secure if she just depended on herself, picking up with her old job as a medical secretary.

Even more than the financial ramifications, this decision disrupted my childhood. I remember laying in bed waiting for my father to come home from what I thought was a business trip, listening for the door to open. Finally I got out of bed and asked "when is daddy coming home?" Overwhelmed with frustration, my mother shouted "he isn't" and sent me back to bed.

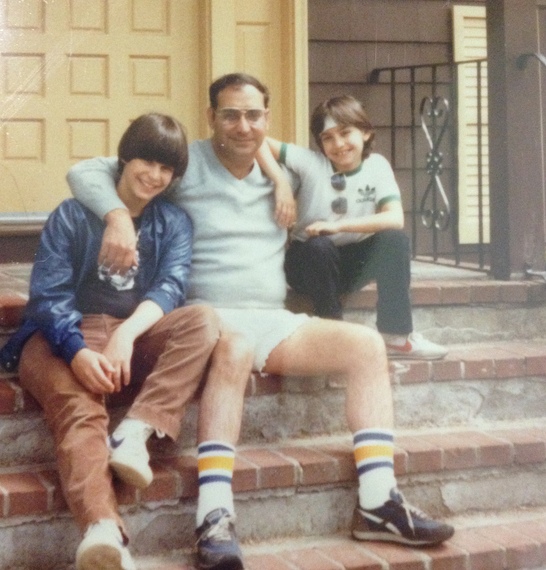

Throughout almost the entire remainder of my childhood, my father was a continuous presence. Whether he was living with his parents, based in a luxury apartment, or in a grimy rent-controlled flat, I visited him on weekends and for a month during the summer. He was a great storyteller, and the themes and settings of his stories sometimes reflected his war experiences. Often the protagonists were lone warriors charged with protecting a village from marauders in the spirit of "The Magnificent Seven," closely based on his view of his Special Forces mission in Vietnam.

During the weeks, I spent with him, I learned to never approach him at night. I remember waking up one night after a bad dream to the loud buzz of the air conditioner. I walked over to his bed for a hug -- as my own kids do so often today. I made it to within around five feet of him. He uttered a loud war cry and was on his feet within seconds with his hands poised to strike. His only explanation for this was that I woke him up. I went back to bed with my heart still pounding within my chest.

Instead of an after-camp program, such as we have today, a camp counselor deposited me at his travel agency on Boston's North Shore. A red brick multi-level commercial complex, it housed the travel agency, a massage parlor, and a tavern named after Las Vegas's Caesar's Palace. I could often find him in this cavernous, frigid, pitch-black bar with leather-backed booths and stools, sipping J & B on the rocks. McCartney's "Let 'Em in" or Lou Rawls' "You'll Never Find" would be playing on the jukebox. I'd take refuge playing Pong or Breakout.

He drank and drove. Well, to be fair, he drank, smoked Marlboro 100s and drove. Once driving outside of my grandparents' high rise apartment, he found it difficult to navigate a complicated traffic circle. Instead of patiently waiting, he thrust his 1976 Chevy Monte Carlo towards an approaching vehicle and muttered "I'll fight you."

Ultimately his travel agency, powered by unique and ahead-of-their-time money-making schemes and sometimes questionable gambling junkets to Las Vegas, failed. Here he was undaunted. He had one last scheme in him. He devised a plan for a trade show based on everything the people we came to know as Yuppies did in their spare time. He called it "The Leisure Time Show" and put it on in Boston's Hynes Auditorium. He secured coverage on local television and appearances from former members of the New England Patriots and other local celebrities. When my sister and I arrived, he had his feet up on a desk and was drinking a scotch. The show broke even, but did not make enough money to support him. His former colleagues at another travel agency, Sheldon Adelson, (yes, that Sheldon Adelson), and Irwin Chafetz, got into a similar business and thrived. This only compounded his suffering.

He was constitutionally incapable of working for someone other than himself. A man who had been a member of America's most elite military organization could not follow orders. We couldn't figure it out. It was with the failure of the Leisure Time Show that things really got bad. For the one and only time in my life, he dropped out of sight. We didn't hear from him. We didn't know how he was surviving. Where once he had told me about the Jewish ritual practice of the bar mitzvah, he was largely MIA as I studied for mine. My mother toiled with all the financial and logistical preparations. Ultimately, he snuck into the synagogue and heard me daven. But he quietly absented himself from the party.

After a few months, he seemed to rally somewhat. He stopped drinking cold turkey. We were seeing him again. We heard rumors that he might be driving a cab. I didn't dare ask, but my younger sister was spunkier. She started to talk to him about television. She asked him if he watched the sitcom "Taxi" and what he thought of Alex, the Jewish character around my dad's age. He confessed that he was driving a cab, but insisted he wasn't going to do it for the rest of his life.

We still visited him frequently. Movies were the top activity. At age 10, I accompanied him to "Apocalypse Now." He had been excited to see this Vietnam movie featuring Green Berets directed by the director of "The Godfather." I remember him shaking his head and muttering at some of the scenes. By the time Marlon Brando and his bizarre compound came onscreen, I was terrified. Finally he got up. "I can't take this any more," he said as he led me out. Three years later, he took my sister, then age 11, and I to another movie whose lead character was a Green Beret, called "First Blood." In retrospect, I'd say he was more drawn to the film by his taste for Stallone than the Vietnam backdrop. But it's interesting to think that fierce, bloodthirsty Rambo served as the public's model of PTSD during the 1980s. By 1982, people were starting to understand that the war had damaged some of its soldiers. Yet that model didn't fit tortured, bespectacled, cerebral Jerry Gitell.

As his problem drinking subsided, other problems such as insomnia, anxiety and self-loathing intensified. He had two bedrooms in his grimy Cambridge apartment but he slept on an old couch with his back to the wall. He kept his loaded service revolver in the closet and an eye on both doors.

Walking home from class at Harvard with classmates, I'd often bump into him at Elsie's Lunch, grabbing a brisket sandwich between fares. "That's my dad," I'd say to my friends, who looked on with shock. I was staying with him prior to moving into my house at Harvard after news had broken that Sadler had been shot in Central America. For the first and last time in a very long time, he had been drinking. I found him in the dark. He told me I didn't understand. He named the names of men I had never heard before, friends killed in Vietnam. "I should have died," he said. I walked out to roam the streets of Harvard Square. My heart pounded just as it had years earlier.

A decade of suffering followed for him. Shortly before 9/11, he announced to us his plan to "change his life" and move to Las Vegas. For a moment, the move looked like it would be a success. He procured a job as a substitute teacher, stopped smoking, and even appeared as a military analyst on local television on the U.S. effort in Afghanistan. But it didn't last. His job as a teacher ended.

Finally, his sister's husband, a union man named Chuck Hawk, convinced him to visit a Vet Center. There he started to talk and listen. The therapists there focused on a "veterans group talk." As my dad went each week to talk to his group, the Veterans Administration certified him as having "PTSD." This came with a small stipend that enabled him to survive and mitigate some of his tremendous suffering.

In the meantime, an old sergeant major spotted my dad wearing a hat with the Special Forces insignia in a bagel shop. He invited him to attend a meeting of the local chapter of the Special Forces Association. My dad attended and was astounded to learn that they sang "The Ballad of the Green Berets" at each meeting. He had finally found a home.

Less than a week after he died unexpectedly, we gathered at the Veterans Memorial Cemetery in Boulder City Nevada. A green beret was placed in front of his pine coffin along with a pair of paratroop boots. At the end of the ceremony, his Green Beret colleagues, his friends from his veterans group and family, sang familiar words: "Put silver wings on my son's chest; Make him one of America's best; He'll be a man they'll test one day; Have him win the Green Beret."

Seth Gitell can be reached at sethgitell@gmail.com

Earlier on Huff/Post50: