In the early 1970s a generation of young people fed up with corporate culture and looking for a deeper purpose -- their minds filled with fantasies of growing their own food and being self-sufficient -- moved out of their urban dwellings and into a rural landscape. There, on their own and as members of farming communes, they discovered the harsh realities of subsistence agriculture and in some cases with time and hard work carved out extraordinary lives.

Forty years later a new generation of idealistic do-it-yourself 20-something homesteaders and followers of the "locavore" movement are moving to the countryside. These newcomers face impossibly-priced agricultural land and extreme weather, but with these challenges also comes something the first generation of back-to-the-landers did not have -- the support of the media and an increasing section of the general public that wants to know where their food comes from and are willing to drive farther and pay more in order to support small family farmers.

Joe Conway, a 30-something freelance writer based in Portland, Maine was in the process of trying to figure out how he and his family could buy some land and grow their own food when he met Ben and Taryn, a young couple who had just graduated from agricultural school, and after putting in time on farms, moved in with Ben's dad, a back-to-the-lander who moved to Maine from Boston in the late 1970s. Conway found them to be more pragmatic than Ben's parents in that they recognized the flaws in our food system and economy, but he said rather than opting out, they are opting in, looking beyond their own well-being and trying to create positive sustainable changes as part of a growing community of people who support the local food movement.

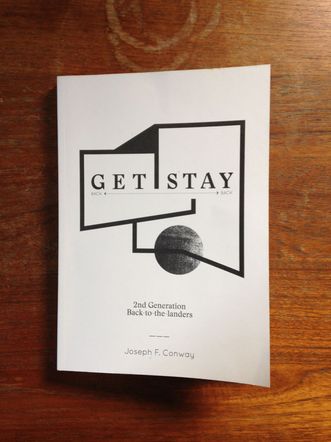

According to Conway, the idea of this young couple's commitment to moving home and going back-to-the-land inspired him to write his first book Get Back Stay Back: 2nd Generation Back-to-the-Landers in Maine. The book, which took him nearly three years to write, is about the evolution of the back-to-the-land movement from the late 1960s to today as told via a collection of 13 narratives by "second generation back-to-the-landers."

Agrarian traditions in this country have roots back to our founding fathers Conway reminds the reader. He recognizes the benefit young "modern" farmers and "do-it-yourselfers" seeking an off the grid existence could have if they acknowledge the hard-earned lessons of their predecessors and create relationships with them, something second-generation farmers returning to the land already understand and benefit from.

I had the chance to talk with Conway recently about his new book and what he learned from spending time with today's young farmers.

What is your ultimate take away from the book?

That it takes an unbelievable amount of work to grow food on any kind of scale, and that the more people learn that, the better off we'll be. I think that's ultimately the thing that the back-to-the-landers in the 70s learned too -- or maybe more generally that simplicity is really a very complicated. Humans, we have a habit of idealizing life in the country -- 'away from it all' -- as we like to refer to it, people have been doing it as long as there have been cities.

How did you find the people you interviewed?

From Ben and Taryn, it spread out - for lack of a better term - organically. They introduced me to friends who introduced me to friends. The community of young farmers in Maine is actually pretty small, homesteaders, even smaller. I also got some help from a wonderful old back-to-the-lander who had just gotten out of farming after 30 years and now pilots a great organization called Slow Money Maine. She advocates for alternative economies now -- her name is Bonnie Rukin.

How do you identify with them?

I think it's impossible not to identify with them. Granted, I'm a super idealistic person, but I tend to worship the ground that farmers and teachers walk on. If you don't, go ahead and try farming or teaching for a week and your perspective will change. I've done both, and understand intimately the financial realities associated with both. You've really got to love it, or, as I came to see it, simply not be able to not do it. I will always find people with that kind of compulsion for anything fascinating.

I would think your connection to Maine's farming community and food has greatly changed as a result of writing the book. How has writing this book changed the way you eat?

As someone who loves to cook, I'm been pretty invested in supporting farmers and eating food that doesn't travel a long distance to my plate for a while. I mean, I'm a writer, and my wife is an artist, and we're not people of means -- so I feel the pain of the $5/pound tomato fully. I definitely have a greater appreciation for why things cost what they do now though -- food is just very expensive to produce, hardly anyone gets rich by doing it and it's incredibly hard work. I subsidized the research phase of writing the book by working on a mussel farm and in a restaurant kitchen, and the margins are the same across the board -- paper thin. I also grew up driving past dairy farms all the time and never understood that where ever there are milk cows grazing, there's someone in a nearby house who gets up to milk them at 3:30AM every... single... day. 'The cows don't know it's Christmas,' as they say. That some people choose to also go the long way around, and produce food for us in a way that's not only good for us, but good for the land that they're working and their community, I think is especially laudable -- and certainly deserving of a lot of my hard-earned dollars every week.