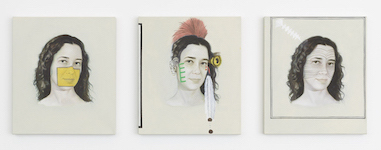

Paulo Nazareth: Sem titulo, da série Objetos para tampar o Sol de seus olhos (Untitled, from the series Objects to Keep the Sun out of Your Eyes), 2010; photo printing on cotton paper

A New York perspective on Brazil's enduringly vibrant art scene

I'VE SPENT THE past week viewing as many of New York's fourteen art fairs as possible. For me, the Armory Art Fair has always happily marked the start of the spring season and the yearly cycle of international art fairs. Attending is a little like going to a gigantic wedding reception -- speaking with hundreds of "family" members over an intensive six-day period. It takes days to walk the Fair's aisles, during which you encounter superb displays of art, catch up with friends and colleagues, collectors and dealers. And this year there were not only the Armory's two piers but the added energy of the Volta Art Fair on an adjacent pier -- let alone the really big thrill of the Independent Art Fair, which was stationed in Tribeca on three upper floors of a new building that featured soaring ceilings that afforded light and space to more than forty well-selected gallery presentations. And that's to say nothing of the deliciously sophisticated ADAA art fair on Park Avenue and the anarchic energy of SPRING/BREAK's 800 artists inside the McKim, Mead & White-designed James A. Farley Post Office Building.

As someone who maintains a home base in São Paulo, everywhere I was asked for my perspective on South America's current outlook and the Latin American art scene. Literally hundreds of people asked me "Who's hot on the Brazilian art scene today?" "Who's buying the new and now?" "When's good for an art tour of Brazil- before or after the Olympics?" "How's the country dealing with the Zika virus?" "What's up with President Dilma and the 'detention for questioning' of former president Lula?" "How about that pessimistic 'sky is falling' vision of the Brazilian art scene in full-fledged crisis that was recently sketched in Artsy?"

My instant response was that I'm so looking forward to one of my favorite art fairs in the world, São Paulo's SP-Arte art fair, which runs April 7-10.

But there's really no simple response to these questions that gives an accurate impression of the Brazilian art scene that I have come to know and admire over the past decade. It's a scene that's taken decades to grow, a complex cultural ecology, resulting in a vibrant Brazilian artistic landscape that's actively engaging international audiences. In my view, the growth of this scene and its underlying cultural currents are far from slacking. It's a scene in which both seasoned cultural institutions and brand new ones are taking wing and finding new ways to support new programming and visionary projects.

Without a doubt, Brazil's macroeconomic conditions are in the midst of a perfect storm: rising unemployment; rising inflation; rising interest rates; governmental corruption; and trade imbalances due to a radical drop in revenues as prices plummet on raw materials (from cattle to oil and iron ore) as these materials are being sold in diminishing quantities to the nation's No. 1 customer China (which is facing its own downturn). But as I've been having conversations about Brazil with dozens of art-world players, I've come to realize that it's far too easy and too glib to collapse the nation's macro conditions into a general fret about the Brazilian art scene; a close look at the granular, microcosmic conditions prevailing at galleries and museums, and with individual artists, gives a different feeling.

It Takes a Village

It takes generations to organically grow a robust art market with a full range of cultural support systems. For a big picture vision of the Brazilian art market, I spoke with SP-Arte art fair founding director Fernanda Feitosa. She told me that at last month's Cisneros Fontanals Art Foundation (CIFO) conference Dutch-based art market expert Dr Olav Velthuis said, "The boom that the contemporary art market in Brazil witnessed over the last decade is only the latest stage in a much longer process of art world emergence. This emergence has been a slow and tedious process, as it almost invariably is (Europe and the United States are no exception in that respect). It is the result of the persistence, passion, and painstaking efforts of many people, some professional, other amateur, some rich, others poor, some local, others foreign, some acting on their own, others concertedly."

Feitosa also said that during her 2004 research period before launching the SP-Arte art fair in 2005, she discovered that "no international galleries would come to Brazil. Global galleries said Brazilian audiences didn't have a global vision. And then in 2005 when SP-Arte launched, it had one international gallery -- Sur, from Uruguay. And this year there will be 39 international galleries." As to the assertion that Brazilian galleries are only now being forced to actively reach international audiences, Feitosa went on to point out that "it's part of a natural growth process to go global, it is not a sign of weakness. Luisa Strina has been developing an international market for her artists for more than thirty years."

Many have expressed fears about statistics they have seen about falling gallery sales in Brazil. But when you analyze and contextualize the facts, you see that most statistics do not break out national versus international sales, nor do they depict the national sales in a telling, granular way. For example, the Artsy article cites a sales drop for Galeria Millan, but when I spoke with Galeria Millan partner Socorro Lima, I discovered that the article neglected to mention the bravura, new São Paulo gallery space that Galeria Millan opened three months ago in Vila Madalena, which is even bigger than their primary space. The new space opened with a solo show by master painter Paulo Pasta that sold 110 percent -- meaning that the show sold out, along with Pasta works already in the galley's inventory. Lima said that while national sales are down, international sales are up. Nor does the article touch on the confidence I heard from other gallerists who are expanding their galleries: Nara Roesler Gallery opened a Rio de Janeiro space last year and Fortes Vilaça is scheduled to open an exhibition space in Rio de Janeiro in September 2016.

Fernanda Feitosa reminded me that "growing an art audience takes time. When SP-Arte began in 2005 it had 6,000 visitors. In each subsequent year the audience has grown. The 2015 edition brought 23,000 attendees, a quadrupling of the viewing audience. And all the while we've been building our VIP programming, so that we cultivate leading art collectors from both Brazilian and the international scene. Of course, audience cultivation requires many other elements, including arts reporting. Since our fair began, four art magazines have launched: ARTE!Brasileiros, Select, ZUM, and Dasartes."

And competition helps to build audience. Five years ago, the ArtRio art fair launched with great fanfare and began developing its own unique draw of international galleries and Brazilian galleries wishing to reach Rio de Janeiro's unique audience. And with ArtRio's opening a governmental concession dropped federal and state taxes for purchases made during the run of the art fair, which permitted Brazilian collectors access to standard, international art prices. That move by ArtRio provoked SP-Arte competitively to introduce the same feature at their art fair -- so that during the past decade these two art fairs have done more than increase the visibility of Brazil's growing art market: they have created unprecedented breaks in onerous trade barriers.

Below, installation view of Galeria Millan's new gallery space, with a painting by Paulo Pasta

Cultural Institutions

For a big picture view of Brazil's cultural institutions and their present standing, one of the leading museums in Brazil is the Pinacoteca do São Paulo. The museum's Director of Institutional Relations, Paulo Romani Vicelli, wrote to me saying that "the crisis is real, but it´s not melting our solid institutions. Last year Pinacoteca celebrated its 110th anniversary, showing its vitality and openness to new ideas. Our newly created patrons group purchased the first performance art work for the collection -- Mauricio Ianês' O Nome/The Name). Moreover, 2015 delivered record attendance for us, with over 570,000 visitors."

The growth of art audiences is something that Fortes Vilaça Gallery partner Alessandra d'Aloia focused on, during our conversation. "A diverse Brazilian art scene has spent decades building international audiences. Brazilian collectors today are much more aware about their role in building the art market. And in the past couple of years museums are making such a big effort to make active committees and grow their patron groups. Patronage takes time to build. And it's a new generation that is beginning to engage being patrons. This is about being conscious about being a citizen in your country. And this big effort being made is bringing change to institutions."

D'Aloia went on to point out that there is a growing group consciousness on the part of Brazilian gallerists. Eight years ago eight galleries formed ABACT, a collective action group that today has grown to fifty member galleries who invite collectors, critics and curators to come to Brazil to learn about the art scene first-hand.

One of Brazil's most remarkable contributions to global culture is Inhotim, the art park created by private collector Bernardo Paz that has dozens of dedicated art-filled buildings and installations on a glorious jungle site that is three times larger than New York's Central Park. I've frequently described it as one of the Eight Great Wonders of the contemporary art world, it was begun more than twenty years ago. It started attracting a trickle of private visitors that has become a powerful stream. First opened to public visitors back in 2006, in August 2015 Inhotim reached the two-million-visitor mark.

And what's it like to lead a cultural institution in Brazil today? I spoke with Heitor Martins, president of the board of trustees of MASP/Museum of Art of São Paulo and the former president of the São Paulo Bienal Foundation.

"First, let's acknowledge the economic crisis: the country is under real strain," said Martins. "And the crisis effects everything, including the art scene. But Brazilian arts institutions have never been stronger. Let's look at the culture leaders. In 2009 we revitalized the support of the Bienal, and it continues ro be very stable and healthy, promising a great edition for September. Pinactoca is working strongly and is in good shape. MAC-São Paulo has a new building and just opened, so that the whole collection can finally be seen; a triumph of government support. MASP has in the last twelve months -- in the midst of the crisis! -- revised its board, begun renovating its building, and eliminated debt. And in Rio de Janeiro, MAR, a magnificent new museum has opened. Major institutions are so much better than ten years ago. Previously, our cultural institutions worked on a European model where the state pays for everything. This is changing. There is a market shift. Private people are reaching into their pockets and declaring their love for art and public institutions. Things are working despite the economic environment, and this is great."

Below, Adriana Varejão: Kindred Spirits (2015); oil on canvas in three parts

Tariff Barriers

Unfortunately, many recent dire assessments of Brazil's art scene have remained only on the surface. They declined to take the reader on a more informed journey. The really interesting story here is that Brazilian galleries have been living behind onerous tariff barriers set by the federal and state governments. Art is classified as luxury good, just as a Gucci handbag is, and as such is taxed a very high import surcharge. The result is that it is far cheaper for Brazilian collectors to buy Brazilian artists exclusively, as those artists are much cheaper than international artists of the same stature. So the Brazilian government has created an insulated internal market. What this means is that when the economy weakens, as is now happening, nationwide collectors cut back on their art purchasing and the galleries have to reach abroad for collectors -- which is what we are seeing now. Smartly, rather than sitting still, the most well-heeled galleries are opening international offices and galleries and/or increasing their participation in international art fairs.

Thus the much bigger story that lies untouched -- much more serious than a superficial claim that "the sky is falling falling" (because markets always pulse up and down and back) -- is the need for an examination of Brazil's protectionist economic trade policies. As many have noted, it is these policies that create false economic markets and spread corruption into every aspect of Brazilian life. That is the really alarming story, and one that The Economist addressed a couple of years ago when it placed Brazil among the lowest of 185 countries ranked for transparency in business transactions.

Moving Forward

Three years ago on behalf of Huffington Post, I had the great pleasure of interviewing André Aranha Corrêa do Lago, the curator of a visionary photographic exhibition of Modernist Brazilian architecture that was at São Paulo's Instituto Tomie Ohtake. A renowned economist and Brazil's United Nations-based environmentalist (who was appointed Brazil's ambassador to Japan, during the closing days of the exhibition), Corrêa do Lago shared with me his optimism about Brazil and its future."Demographically, we are a young country. Unlike Europe and Japan, Brazil has a demographically young population. And it is increasingly educated. Amazingly in just a generation, Brazil has wiped out poverty: Brazil's statistical status with the UN used to be that it was graded with one-third of its population living in poverty. Thanks to Lula and due to governmental development, that is no longer the case. Families are encouraged to keep children in school. We now have an educated working class and a growing and striving middle class. We have the trained people to address our nation's problems. We have the tools and the people to create a bright future. The question is: Will we use this to our advantage?"

Corrêa do Lago is one of many accomplished individuals who have shared with me their profound passion for passing culture, education and inspiration to the next generation. I have never forgotten my conversation with him in the halls of the Instituto Tomie Ohtake. His words crystallized something profound. It was a "coming together" of aspiration and vision and possibility. That is Brazil's secret sauce -- its power and strength: the striving and inventive nature of an increasingly vivacious and educated people, to grow, improve, and advance.

Ars Longa, Vita Brevis

The demand for Brazilian artists on the international stage is not falling. There is more and more interest in top-ranked artists who have international presence. Yes, Brazil faces a profound economic crisis. But irrespective of macroeconomic fluctuations, contemporary Brazilian artists are giving powerful voice to the unique experience of living in today's multi-cultural, global community. As such, the international art world is making its vote of confidence by purchasing Brazilian art and showcasing Brazilian artists. Says Galeria Millan partner Socorro Lima, "Brazilian art has entered a powerful new place, because it's now recognized as having a powerful international voice. No longer the "exotic." Only recently has Brazil achieved an equal footing on the global scene. The world is more open and Brazilian art is in a strong place. There are now so many bridges between Brazilian art centers and the world.

Perhaps Mendes Wood DM partner Matthew Wood said it most eloquently, "It's too easy to be focused on troubles.... I am interested in artists. And I look for believers.... I kind of love the artists who are lunatics, that are mad believers.... There is criticism of our culture here in our artists, but not cynicism. That is important to me. Faith. Believers."

I can't help but admire the extraordinary artistic talent, growing diversity, and international cultural vision to be found in Brazil today. This is a vibrant time in which artists and other culture-makers are inventively finding new ways to grow, even under complex economic conditions. CIFO conference attendee Dr. Olav Velthuis may have said it most clearly: "Well before Brazil's economic boom, entrepreneurial gallerists such as Luisa Strina, Thomas Cohn, and Marcantonio Vilaça managed to make a market for contemporary Brazilian art. They did so in times of dictatorship, political corruption, and economic hardship. The present economic downturn will not be able to destroy what has been built up over the course of a century."

Sometimes we all get so caught up in the prices of art and the regular gyrations of the art market that we loose sight of the value of art. Every day and under varied economic conditions, artists are working away creating their personal visions that give us unique insight about our lives and our culture. Long after we are all gone, art is what will remain as the vessel of our civilization. Life is brief, art is long.

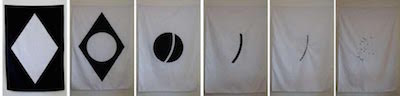

Below: Maurício Ianês: Deletrear lição #1: ideologia (Spelling lesson #1: ideology), 2013; variable dimensions installation with sixflags made of polyester and viscose fabric, metal eyelets