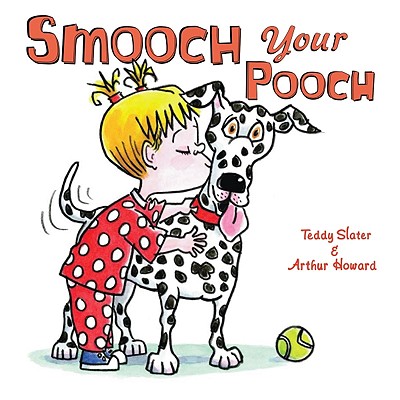

Every Christmas it seems like some child-safety watch group finds at least one or two toys that are dangerous for kids. This Christmas there is one gift that's actually dangerous for both kids and pets. It's an adorable book called Smooch Your Pooch, and its message is so dangerous that even the American Veterinary Society of Animal Behavior (AVSAB) is taking a stand against it. In a press release, they state:

"[AVSAB] strongly advises that parents avoid purchasing the recently released children's book Smooch Your Pooch for their kids. The book recommends that children 'Smooch your pooch to show that you care. Give him a hug anytime, anywhere.' This information can cause children to be bitten."

See the full press release here.

What's the Problem?

While this adorably illustrated book, with its sweet, catchy rhymes, is meant to foster affection for pets, the contents as well as the cover illustration teach kids to hug and kiss dogs; this can cause dogs to react aggressively. No one knows that better than Dr. Ilana Reisner, a veterinary behaviorist at the University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine. Dr. Reisner and her colleagues published a study examining why children get bitten by dogs. Says Reisner, "The recommendations in this children's book -- and even the title of the book -- are potentially dangerous."

That's because many dogs do not like being petted or hugged. They just tolerate it -- at least temporarily.

Reisner elaborates:

"Although some dogs are not reactive about being kissed and hugged, these types of interactions are potentially provocative, leading to bites. In a study we published in a journal called Injury Prevention, we looked at dogs that had bitten children and found that most children had been bitten by dogs that had no history of biting. Most important here, familiar children were bitten most often in the contexts of 'nice' interactions -- such as kissing and hugging -- with their own dogs or dogs that they knew."

Because children are shorter than adults, the bites can be severe. "Sadly, small children are most often bitten in the face and head," says Reisner. "We assume this is because they are bringing their faces close to the dogs."

Given this information, teaching kids to kiss and hug pooches is clearly not safe. But Smooch Your Pooch goes a step beyond and recommends, "Give him a hug, anytime, anywhere."

While some dogs may tolerate or even enjoy an occasional kiss or hug, they may not tolerate incessant kissing or hugging indefinitely. To the dog who needs a break from kids or needs to know he has a safe location where he can choose to be free of constant attention and pestering, these unsolicited hugs can take him to the breaking point -- the same way incessant pestering does for human adults and sibling. The difference is that a human sibling might get angry and hit or scream. Dogs growl, snarl and bite.

So, even dogs who are perfect most of the time can bite seemingly out of the blue.

Of course, to the skilled eye these bites are not random or even unexpected. Reisner's study found, that in addition to biting when they are hugged, kissed, bent over or sometimes simply petted, dogs are reactive when they are approached/touched while resting, when they have anything they consider "high value" (food, toys, a favorite blanket or even the parent), and when they are hurt or frightened.

Based on these research findings, Reisner states emphatically:

"I would not recommend that children take this book's advice to kiss and hug their dogs. After all, dogs do not hug or kiss each other, and it is understandable that they might feel uncomfortable with such displays by children. In fact, bending over a dog and looking directly into its eyes can be seen as a 'threat' in dog language."

Instead, she recommends more appropriate games and displays of affection, such as fetch, going for a walk together (with adult supervision), and even training new tricks. "Training simple tricks can be very rewarding for both the dog and for its young companion," says Reisner. "Dogs like to be warm and comfortable and well fed, and most of all to be near us rather than isolated."

Does this mean you should never hug your dog?

Reisner suggests, "If a family dog is clearly unconcerned about being hugged and kissed, showing affection that way is probably fine."

You can tell when a dog enjoys being hugged because he leans or rubs against you the way a human enjoying a hug would. Dogs who don't enjoy hugs act aloof and may lean or look away, similar to the way a child reacts when you pinch their cheeks affectionately. Dogs who are not enjoying this kind of attention may also show other signs of anxiety, such as yawning, licking their lips, tensing up, or dropping their tail low or between their legs. When we ignore these signals of discomfort, they may try to warn us with a raised lip or a low growl.

Reisner does stress that children should never approach or interact with dogs who are lying down, resting or asleep. Instead, she recommends that children only pet the dog if the dog chooses to come to them. "Pick up a leash and a box of treats, and call the dog to you," she says.

So the rule for kids is: Interact with the dog when the dog approaches willingly. Otherwise, kids should give the dog his own space.

For more information on appropriate interactions between kids and dogs, read: Living with Kids and Dogs by Colleen Pelar (www.livingwithkidsanddogs.com). Read my full review of the book Smooch Your Pooch here. To learn the signs of anxiety and fear in dogs, see Chapter 2 in Low Stress Handling and Behavior Modification of Dog & Cats. To download the research report: "Behavioral assessment of child-directed canine aggression" Ilana R. Reisner, Frances S. Shofer, and Michael L. Nance. Injury Prevention, 2007 October; 13(5): 348-351, click here.