- "The stupidity of school bureaucrats never ceases to amaze me."

- "Pretty soon, just making eye contact with the opposite sex will get you suspended."

- "This kind of thing has gotten to the point where it's sexual discrimination against little boys."

The boy kissed his classmate on the hand. He'd previously been disciplined for kissing her on the cheek and "rough housing" too... roughly. After this last incident, the school suspended him. He is endearing and he's 6 and as so many are fond of pointing out "boys will be boys." But, the girl he kissed without permission is also probably endearing, also 6 and not interested in his touching her. The hard and unpleasant part, for many, is the idea that her right not to be involved in his working through learning self-control is legitimate.

What really seems to be bothering so very many people is the use of the term "sexual harassment," which is what the boy was suspended for. What if the headlines had said, instead, "Six-year-old boy suspended for bullying?" Sexual harassment is bullying. County education officials have decided that the infraction will not be classified as sexual harassment and the boy is returning to school. What news commentators, the mother of the boy and many others debating the 6-year-olds' classroom interaction seem fixated on was this: "Now someone has to explain the term sex to the boy, it's just too early." Just... really?

We're talking to kids about sex all day, every day, without ever saying the word. We do it when grandmothers insist on a kiss and parents make children comply. We do it when we tell girls to "be nice" and "good" when they don't want to. We do it when we tell boys to take what they want from life. We do it when we tell them that God wants them to be "strong." We do it when we watch football games with kids on TV and spend half the game talking about players' girl friends in the stands like they're trophies. We do it when school administrators police clothing and use girl's bodies as props to demonstrate violations of dress codes and reinforce heterosexual norms. We do it when we don't allow children to pick their own clothes and chose their own hairstyles. We do it when we think it's funny to let kids "tease" each other, even though the person being teased isn't interested. We do it when an uncle grabs a nephew and tickles him, even though he hates it and tries to get away. Never. Ever. Saying. "SEX!"

Situations like the one in Colorado arise constantly and are timeless.

When I was 6 or 7 there was a popular playground game, "Kissin' Catchers." The objective of the game was for boys to chase girls until they caught one and kissed them. Usually, the kisses happened under duress, as the girls struggled to get away. Really, that was the game. I HATED this game, but I was really fast and so I could run and hide until the game was over. I still remember hiding in bushes all over my neighborhood, perspiring and anxious, until everyone was done. People made fun of me for staying out of sight and, indeed, didn't want me to play because, by hiding, I was a spoilsport. I could have not played, of course. But, at the time, it didn't occur to me -- these were my friends and this was supposed to be fun. So, I thought, it's my problem that I don't like it. This game probably isn't played too often any more, but I've watched my daughters having experiences in school that mirror the one in Colorado.

Like this one in which a boy in kindergarten was regularly poking a classmate and caressing her arm. She didn't like it, but when she asked him to stop, he would not. He kept on. The girls attempts to make him stop were perceived by at least one adult in the room as her being "over-sensitive." One day, the child explained to her mother that she did not want to go to school and had a stomachache because he was bothering her all the time and she wanted to avoid him. So, her mom went in to talk to the teacher, whose response was to suggest that they take the little girl out of the class and put her in another. Her mother and father had to escalate to the head of school and the little boy was moved to another room.

Whiny little girls?

Difficult, demanding mothers?

Discrimination against boys?

That's absurd. Children have to learn to respect other people's boundaries and listen to their words when they are little. The younger the better because the consequences get more serious the older we get.

According to another study released earlier this year, one in 10 people between the ages of 14-21 have already committed an act of sexual violence. The most insightful finding, however, was that children who engage in these behaviors feel no sense of responsibility for their actions. That makes sense, since one of the defining characteristics of people who abuse other people is a sense of entitlement. It just happens that our entitlements are gendered and we cultivate a deficit of empathy in boys.

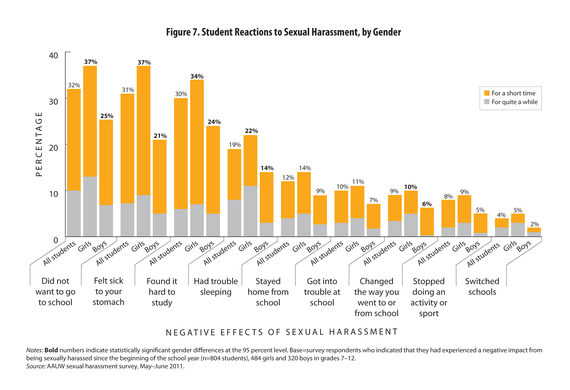

Last year's American Association of University Women's study of sexual harassment in schools, "Crossing the Line" study, revealed that 'Sexual harassment is part of every day life in middle and high school. Nearly half (48%)of the students surveyed experienced some form of sexual harassment... and the majority of them (86%) said it had a negative effect on them." Girls were more likely to be targets of harassment, (56 percent versus 40 percent of boys) and their harassment is "more physical and intrusive." As a result, 22% of girls/14% of boys have trouble sleeping; 37% of girls, 25% of boys not want to go to school; and 10% of girls/6% of boys want to change the way they went to or home from school.

Not only is it problematic in the long-run to enable behavior that routinely involves disrespect for other people's bodies and words, but there are real and tangible negative effects that are ignored and minimized. It's common for kids who experience sexual harassment -- call it whatever you want -- to hear, "it's not a big deal," and to be told that they shouldn't be "so sensitive." This minimizes what they are experiencing, denies their reality and teaches them that their thoughts and words don't matter. For whatever reasons, as shown in this graph from the AAUW study, for girls, the effects of harassment last longer and are more physical.

Schools are in a hard spot. Talking to children about bodily integrity, autonomy, consent, other people's rights -- all precursors to talking about sex -- cannot happen in schools in a vacuum. And conversations like these aren't happening enough in homes, where, frankly, abuses are happening all the time.

Childhood is practice for adulthood. What happens when children don't learn to respect other people's boundaries and words?

Anyone could, given a little time and thought, generate this list.

So, when would people like to start talking to children about these problems? All children need to understand learn what unwanted touching is, how not to do it and to trust their instincts when they are the targets of it. That starts with habits at home and is reinforced by practices in schools. The truth is, no one actually knows what the antecedents to the boy's being suspended were.

There are many ways to talk about sex in age-appropriate ways. Personally, I don't think "sexual harassment" is a very useful term for 6-year-olds, but it is for their parents. The most comprehensive list of ways in which to teach children ages 5-18 about consent that I've read is one written by Julie Gillis, Jamie Utt, Alyssa Royse and Joanna Schroeder. It is a thoughtful and comprehensive catalog of age appropriate lessons. The only think I would add to it, given the reality of sexual abuse and violence, is to give children the language and permission to say "no" to people with authority.

In response to this Colorado incident, there was an awful lot of, "What's the harm? Kids steal kisses all the time." An interesting expression since, generally speaking, people steal things that they have no right to. They actually are, to use a really old-fashioned explanation, "taking liberties." I know how cute it is when little kids seem to love one another and emulate the adults around them who do the same. They hug, they kiss, they giggle. But, when it ceases to be fun for one of them, they have to stop.

Our ideas about bodies start in childhood, and that's when we have to consciously shape them. Even though 60% percent of Americans know a survivor of domestic violence and every one of us knows survivors of sexual assault, 73% of parents with children under the age of 18 have not talked with them about either. But, you can be sure of one thing: By NOT talking to children about their bodies, their boundaries, their rights and the entitlements others might feel about them, we ARE talking to them. That's the problem schools are having.