"How will I ever learn to be a good writer?"

It's a scary question -- and the hell of it is, the more you appreciate good writing, the scarier it gets.

But it turns out there's a non-scary answer to how to be good: just avoid being bad.

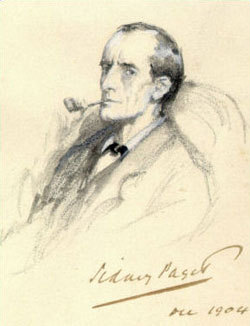

Think of it as the Sherlock Holmes technique: "When you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth." (The Sign of Four)

One of the best ways to do that is also one of the simplest: cut out the adjectives and adverbs. Instead, choose the right nouns and verbs.

Consider the difference between these descriptions:

1. It was an amazingly big house.

2. The house covered most of a half-acre.

The first one is weaker. That's because it merely asserts: "Trust me, it was big!" But unless readers know you personally, they have no reason to trust your assertions.

The second one doesn't assert the size of the house, it causes us to experience it in our minds. Thus the meaning of the old, true aphorism, "Don't tell, show."

Using an adjective or an adverb is like boasting about how strong you are. Far more persuasive just to pick up something heavy.

One more example, which I stumbled across a moment ago on the web (and changed slightly to protect the innocent -- we all write like this sometimes):

Through quantitative data and robust visualizations, we can show...

Why do we need the adjectives? Why not just "data and visualizations"?

This modifier-laden style of writing is so common that it has become standard of "serious" prose. But the adjectives aren't serving any useful purpose, they're just pumping up a vague sense of importance.

Especially that "robust." What would make a visualization robust? Is it being displayed on granite?

If you practice casting this kind of skeptical eye on your own writing, I predict it will get better, fast.

But don't just trust me. I'll leave you with two of my favorite quotations, from two of our best writers:

"The adjective hasn't been born that can pull a noun out of a tight spot."

-- E.B. White.

"When you can catch an adverb, kill it."

-- Mark Twain