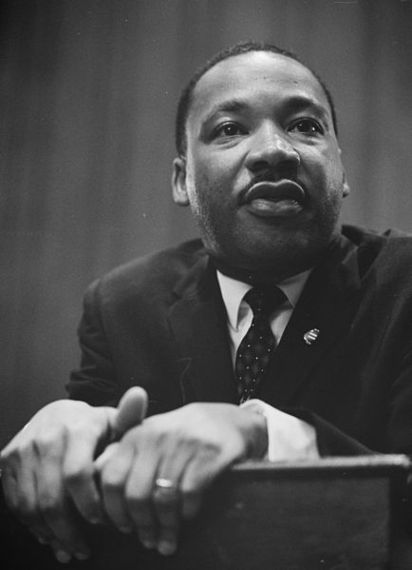

This year, on Martin Luther King Sunday, my church did what thousands of other churches did, which was to retell the story of King's work and ministry and sacrifice in the Civil Rights movement. It's always moving and emotional. It's hard to believe that only one generation ago people were being shot, bombed, killed, hanged, arrested, tortured, threatened and beaten all because they believed in the dream that all God's children get a berth on the boat. It's a dream that all of us should have known and shared already, not one that some young black Southern preacher had to fight and die to tell us about.

But every year when we put on that service, I wonder to myself where King would be today on some of the divisive and polarizing issues of our time. For example, in just the last few weeks the news has been full of stories about Federal Court decisions declaring that bans on same gender marriages are unconstitutional, and I've wondered where he would stand on that. What would King say about marriage equality?

The short answer, of course, is that nobody knows. Homosexuality was in the closet in King's day so no one can say for certain. There are, however, a few clues as to what his personal views might have been and--though my conservative friends would probably disagree--to me they make a fairly good case that he would be on the side of marriage equality.

Perhaps the most convincing "clue" that King would have supported gay rights is that his widow, Coretta Scott King, publicly said that he did. After his death she spoke out for same gender equality on a number of occasions, and believed that she was carrying on Martin's ministry when doing it. In a somewhat twisted affirmation of her work, her funeral was picketed by the famously bigoted Westboro Baptist Church who marched outside with signs saying "No Fags in King's Dream."

In a speech in 1998, at the 30th anniversary of his death, Coretta linked King's ministry to the work of liberation for gays and lesbians. "I still hear people say that I should not be talking about the rights of lesbian and gay people and I should stick to the issue of racial justice," she told the audience. "But I hasten to remind them that Martin Luther King Jr. said, 'Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.' I appeal to everyone who believes in Martin Luther King Jr.'s dream to make room at the table of brother- and sisterhood for lesbian and gay people."

Another interesting clue is that several of King's supporters were gay and he gave them places in the movement and worked with them without any sense of distance or concern. The most visible gay supporter of King was Bayard Rustin, who had been an advisor to the bus boycott in Montgomery and was the driving force behind the 1963 march on Washington. He was openly gay, which was very rare at the time, and had once been jailed on a "morals" charge, which meant in the day that he had been accused of having a male lover.

Over the years a number of King's influential supporters, including the board of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and even President Kennedy, urged him to distance himself from Rustin because of the potential harm it might bring to the movement. But for the most part he refused. On one occasion, however, he did capitulate. It was before the 1960 Democratic Convention in Los Angeles. King and the leaders of the movement were planning a protest out in front of the convention hall, and Rep. Adam Clayton Powell, one of the most influential black political leaders of the time vehemently opposed it. He went so far as to threaten that he would publicly accuse King of having a homosexual relationship with Rustin if they did not call off the protest. The threat was real, and--rightly or wrongly--King relented. The march was cancelled and Rustin resigned from the SCLC.

However, two years later, when the leaders of the Civil Rights movement was planning the massive march on Washington, King invited Rustin back in to be its central organizer, and this time he stood his ground. Interestingly, Strom Thurmond, the famously racist Democratic Senator from North Carolina, went to the Senate floor again claiming a relationship between the two and decrying the fact that the march was being organized by a "pervert." But this time, perhaps shamed by his earlier capitulation, King stood his ground and the march went on. King even had Rustin be the one to read the list of demands that the gathering was going to be presenting to Congress. Over a quarter of a million people gathered on the Washington Mall that day and the event was a watershed in the history of the movement.

Another clue, and one that was deeply embedded in King's heart and faith, is the theological theme that he called the "beloved community," his way of describing the vision that God had for all of creation. God did not intend that the Earth be embroiled in wars, bigotry, economic disparity, or ethnic cleansing, but a "holy mountain" where "they will not hurt or destroy."

He once said that for us to survive as a people, "our loyalties must transcend our race, our tribe, our class, and our nation." And that is because "we are tied together in the single garment of destiny, caught in an inescapable network of mutuality." In his first published article, back in 1956 at the height of the Montgomery bus boycott, he stated that the goals of the newly formed SCLC were "reconciliation ... redemption, the creation of the beloved community."

It's hard to believe that he could believe in such a sweeping vision of God's inclusiveness and at the same time believe that some people in God's creation were more "equal" than others. And interestingly, soon after he wrote those words he invited Rustin to come down to Montgomery and assist him in organizing the boycott.

In one of his first published articles he stated that the purpose of the Montgomery bus boycott "is reconciliation,...redemption, the creation of the beloved community." In 1957, writing of the newly established SCLC, he said their goals were for "genuine intergroup and interpersonal living." And in 1967, in the last book that he ever wrote, he said that "Our loyalties must transcend our race, our tribe, our class, and our nation . . ."

Again, it is difficult to be certain of the non-public beliefs of a man who died so many years ago, but it's also hard to believe that someone who had such a huge heart would want to close it off to those who had a sexual orientation different from his own. In 1968 he preached a powerful "sermon" at Riverside Church in New York City, announcing his opposition to the ongoing war in Vietnam, from his emerging global, inclusive, perspective. He closed with these words, quoting from Isaiah 40: "Our only hope lies in our ability to recapture the revolutionary spirit and go out into a sometimes hostile world ...With this powerful commitment we shall boldly challenge the status quo ... and thereby speed the day when 'every valley shall be exalted, and every mountain and hill shall be made low; and the crooked shall be straight and the rough places plain."'