"Fixed rope" is a flimsy euphemism for thirty meters of braided nylon, half the diameter of my little finger. It's the same lime green colour as my heavy Koflach boots and dangles from the top of the gulley like a fragile spider's thread. Phurbu has gone ahead and anchored this rope amongst the rocks at the top of a snow chute. Nobody in our team has put on crampons or fastened a jumar. We haven't even reached advance base camp, after which the real climbing begins. Yet this funnel of hard packed snow and ice looks treacherous to my untrained eye, a long white tongue protruding from the jaws of the ridge above. Kicking at the snow to find purchase on the slick surface, I try not to think of the drop below. Clutching the rope with one hand, I struggle to ascend the 70 degree slope, like a beetle crawling up a blank sheet of paper.

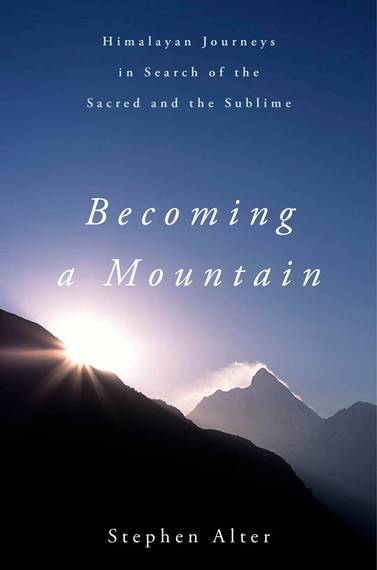

Why am I doing this? What purpose does it serve? Where on earth am I going? These are questions I ask myself more than once in the course of my journeys to Bandarpunch, Nanda Devi and Kailash. I've never aspired to be a mountaineer, though I've been trekking in the Himalayas all my life. Of these three mountains, the only one I attempt to summit is Bandarpunch, at 6,316 meters, a relatively modest peak. This is a mountain I have seen since childhood, rising directly to the north of my hometown, Mussoorie. For me, it represents a constant, reassuring presence that holds my gaze whenever I look out upon its twin summits and the broad snow-covered ridge between. Bandarpunch means the monkey's tail and gets its name from an episode in the Ramayana, when Hanuman, lord of the apes, flew here to find the herb of eternal life, which cures fatal wounds.

My pilgrimage through these mountains is a search for healing and recovery. Climbing Bandarpunch, I seek to shrug off the residual trauma of an attack that my wife, Ameeta, and I suffered on July 3, 2008. The peaceful seclusion of our home in Mussoorie was destroyed by four intruders who beat and stabbed us, then left us for dead. Now, in the sheltering embrace of these mountains, I try to reconcile myself to those violent memories.

Nanda Devi is the "bliss-giving" goddess and patron deity of Uttarakhand. The happiness I find along her wooded trails releases me from fear and anger, blessing me with quiet contentment rather than the ecstatic joy that animates her devotees. I follow several paths approaching Nanda Devi, the second highest mountain in India. Curzon Trail takes me over the Kuari Pass, which offers one of the most dramatic views in the central Himalayas. Another trek leads to Roop Kund, a mysterious lake full of human bones, the remains of pilgrims who died five hundred years ago while offering penance to the goddess.

The third mountain that draws me into its orbit is Kailash, which many believe stands upon the threshold of transcendence. It lies across the main bulwark of the Himalayas in western Tibet. As I circle its summit on foot, along with hundreds of other supplicants, my quest is far less certain. Being an atheist, I do not believe in salvation or comforting myths of celestial gateways to promised lands like Shambala, yet my persistent doubts lead me forward as resolutely as any Hindu mantras or Buddhist prayers.

Becoming a Mountain is a travel memoir. Like my earlier book, Sacred Waters: A Pilgrimage to the Many Sources of the Ganga, it explores the mysteries that lie beyond each destination as well as the confluence of natural history, myth and Himalayan lore. More than the temples, wayside shrines and chortens that I encounter, it is the living world that restores my confidence in the future: the pale white petals of a brahmkamal flower blooming just below the snowline; the watchful eyes of a flying squirrel in a tall fir above my tent; the iridescent wings of a moth; or the shrill alarm call of a bharal ram that knows I am hidden in the rocks.

Extreme sportsmen and women challenge themselves against the magnitude of the Himalayas, scaling vertical walls of stone, skiing down glaciers, or hurling themselves off precipitous cliffs and plunging unfettered through the air until a tug of the ripcord releases them from the fatal pull of gravity. My encounters with these mountains are far less daring, producing equanimity rather than adrenalin. At the same time, however, I also test the limits of death and immortality.

Tom Longstaff, a Scottish doctor and Himalayan pioneer, has written: "To know a mountain, you must sleep upon it." My book tries to capture the dreams and nightmares that confront us as we lie upon rocks and snow, protected by synthetic membranes thinner and lighter than our skin. Monsoon storms illuminate my tent with electric brilliance while the earth beneath me trembles as thunder roars. Nineteenth century writers and alpinists described mountains as being a realm of "the sublime." While this word has been debased and diluted over time, it's original meaning defines a primal fascination for mountains, their umbilical connection to man. The sublime suggests a paradoxical blurring of emotions. Our appreciation for the beauty and scale of a mountain landscape is accompanied by equally powerful feelings of horror and dread. This provokes a human longing to confront and comprehend the forces of creation and destruction.

One chapter of Becoming a Mountain is titled "Writing With My Feet." This book was composed as I walked along pilgrim trails, waded through streams and scrambled over glacial moraine. For some, writing may be a sedentary process, but for me it comes out of a need to wander, escaping lassitude and sorrow while pursuing questions whose answers lie several corners on ahead. Bruce Chatwin has written: "My god is the god of walkers. If you walk hard enough, you probably don't need any other god."

As I cling to the nylon rope and kick steps into the snow, while attempting to climb Bandarpunch, I wonder if I will make it off this mountain alive. The contrast between the danger I face and the ethereal landscape that surrounds me, evokes a sense of the sublime. When I finally reach the top of the gulley, where the rope is anchored, I can see more snowfields farther on, disappearing into the clouds. A rainbow encircles the sun and the snout of a glacier glimmers like a crystal fortress with frozen battlements of ice. But here on this mountain we have passed beyond the reach of metaphors and symbols. Language seems meaningless even as each muddy footprint in the snow recounts a story. Tonight we will sleep upon this mountain and dream about the route ahead, as well as the desires and fears that brought us here. Each of us seeks solace in high places, whether we reach the summit or not.

Becoming a Mountain is published by Arcade (2015)

For more information go to www.becomingamountain.com

A version of this article appeared in The Outdoor Journal.