On a recent "Homeland" episode, Carrie Mathison strode purposefully past a wall scrawled with a rather incongruous message: "Homeland is racist." Despite the fact that the message was written in Arabic, the fifth most widely-spoken language in the world, apparently no one on the "Homeland" set noticed. Throughout the episode, the camera pans blithely past messages as varied as "Homeland is NOT a series," "The situation is not to be trusted," and "This show does not represent the views of the artists." Down one dark alleyway one can even glimpse a literal Arabic transliteration of the hashtag #BlackLivesMatter.

This powerful act of textual subversion, a literal mise en abîme, was broadcast worldwide and publicly announced in an English-language statement posted online by three German-based graffiti artists: Heba Amin, Caram Kapp, and Stone. In their brilliantly crafted and pointedly written statement, they describe how they were approached by the show's producers in the summer of 2015, who were looking for "Arabian street artists" to decorate the set of the refugee camp, which was being painstakingly reproduced by the set designers in a former animal feed plant outside of Berlin.

The call for "Arabian" artists was probably the first sign of the superficiality of the producers' understanding of the Middle East. "Arabian" is an adjective that modifies people or things specifically originating in the Arabian Peninsula - not speakers and writers of Arabic, the proper term for the language. The artists appear to have appropriated the misnomer in a further ironic snub.

In perhaps the worst affront, the producers provided the artists with images of "authentic" Arabic graffiti as an example of what they were looking for. The only problem was that their examples turned out to be pro-Assad graffiti. It's difficult to imagine a greater insult in a refugee camp housing Syrians fleeing Assad's barrel bombs. Confronted with the act of artistic sabotage, Alex Gansa, the show's creator and executive producer, told a reporter, "as Homeland always strives to be subversive in its own right and a stimulus for conversation, we can't help but admire this act of artistic sabotage."

While Homeland wants to think of itself as being subversive, it's actually following a script that has dominated American television and film for decades. Take, for example, the portrayal of Native Americans during the heyday of Westerns between the 1930s-1970s.

Just as in Homeland, Westerns often developed their narrative tension around disputed lands or around contested ideas of governance and sovereignty, but they made invisible the fundamental context of the disputes: land claims. The stories then became stories of good people simply trying to make their way in a hostile place while making the world better in the process.

Like Homeland's portrayal of Mathison, in the case of Westerns, storylines often feature families trying to make a better life for themselves on a hostile frontier, or they portray the army as simply trying to make that possible. Devoid of a deeper discussion of the underlying tensions, directors could then portray any who tried to hinder settlement as fundamentally irrational, aggressive, and hostile.

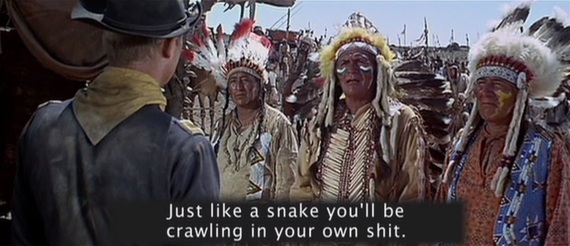

But as with Homeland, Native American actors often found powerful ways to subvert the dominant narrative, often, in the process, using humor to make the director look like an ignorant fool. For instance, in the 1964 movie "A Distant Trumpet" the Navajo actors were told to translate their lines into their own language. One Navajo actor took the opportunity to address a white actor dressed as a cavalry officer with the following statement in Navajo: "You're like a snake crawling in your own shit."

In another 1964 classic, "Cheyenne Autumn," Navajos playing Cheyenne Indians inserted humorous off-color remarks and insulted the commanding officer, much to the amusement of other Navajo speakers, audience members, and Neil Diamond (Cree), director of the documentary "Reel Injun" who documents the "Distant Trumpet" translation in his 2009 film.

Obviously, these subversive acts make plain Hollywood's limited representational sphere for Arabs, Native Americans, and people of color, placing them in stark - and violent - contrast to the richly detailed sphere accorded to white American and European characters.

The subversive graffiti campaign worked because not a single Homeland producer checked back in to read the Arabic messages painted on the walls.

As we are entering our thirteenth year of war in the Middle East, we'd like to ask the producers of Homeland, isn't it about time you learned a little Arabic?

And, maybe a little more Navajo too?

Erika Bsumek is an Associate Professor of American History at the University of Texas at Austin. She is a specialist in Native American history and has written about on how Navajos are represented in American culture.

Stephennie Mulder is an Associate Professor of Art History and Middle Eastern Studies at the University of Texas at Austin. She is a specialist in Islamic art and architecture who worked for over a decade in Syria.

Bsumek and Mulder are public voices fellows with The OpEd Project.