I was excited to read that on March 18, 2014, President Obama will award 24 war veterans the Medal of Honor, the country's highest commendation for gallantry. Nineteen of the recipients are African-American, Latino, and Jewish men -- only three of whom are still alive -- who fought in World War II, the Korean War, and in the Vietnam War. All had received the second highest award for combat valor -- the Army's Distinguished Service Award -- and their cases were considered anew as a result of a congressionally-mandated review to ensure that deserving recipients had not been passed over due to prejudice.

The news caught my eye because ever since I was a small boy, growing up in Philadelphia, I was told stories about my uncle Herman "Chuck" Drizin's bravery in battle at Iwo Jima, an epic battle during World War II that claimed the life of my uncle and thousands of other brave American and Japanese soldiers. My uncle Eddie -- a Jewish war hero who fought in the European campaign liberating France from the Nazis -- told me that the only reason that Herman was denied a medal was due to anti-Semitism. So with the benefit of a scrapbook of old newspaper clippings chronicling my uncle Herman's life and the vast resources of the internet, I set out to see if I could verify Herman's bravery and determine whether he had been slighted.

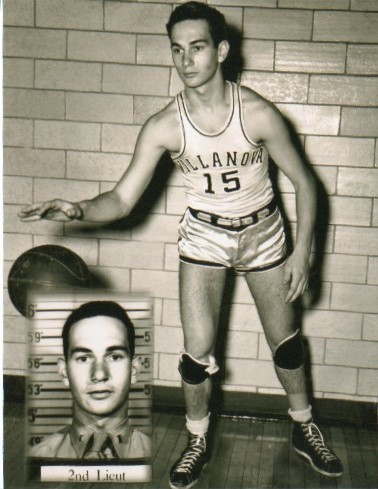

The scrapbook is a family heirloom, filled with pictures, letters, and newspaper articles that chronicled my uncle's life and death. As a boy, I discovered it in a drawer in the garage and throughout my childhood, I often read and re-read the fading newspaper clippings. I was naturally drawn to the articles about Herman's athletic exploits. A star basketball player for Villanova University, Herman was the only Jew in Villanova's starting five when he helped lead the Wildcats to a 19-2 record in 1942-3, the highest winning percentage of any team in their illustrious basketball history. A true team player, who valued an assist as much as a basket, Herman also was a fine shooter. I remember beaming with pride when I read that a former teammate who became a professional baseball scout described my uncle as a "6'2" sharpshooter" who "could do it all" and who was a sure bet to make the fledgling NBA.

As I got older, I became more interested in the details of my uncle's death. My uncle was a Second Lieutenant in the Second Battalion, Company "E," 23rd Marines of the Fourth Division, Iwo Jima. My uncle was in the first wave of Marines to land on Iwo Jima in February 1945. What he saw and met when he got there must have seemed like hell on earth. The rocky and hilly terrain situated above the beaches of volcanic ash made it especially tough going for the attacking Marines, particularly when it rained. The terrain effectively neutralized the American Sherman tanks and required the Marines to take the island inch by inch, foot by foot, in a full frontal assault on the Japanese positions with rifles, machine guns, hand grenades, flame throwers, and bazookas. As they advanced, the Japanese soldiers rained gunfire down on them from every direction.

My uncle was the leader of an attacking platoon that penetrated deep into the Japanese defense zone east of Iwo's sulphur pits in the early stages of the battle. The articles from the Philadelphia papers described how he and his squad of 13 men, while cut off from their unit, advanced a quarter of a mile into enemy lines, destroying three Japanese tanks and killing a dozen soldiers while suffering only one casualty. A Marine correspondent's description of the unit's heroics, recounted how he and his men "dodged from hill to hole, hiding behind blasted tree stumps and rock piles, and had to face not only Japanese fire but also bombing straffing and rockets from American planes, which could not know that the small group 300 yards ahead of the front lines was a Marine patrol."

News of my uncle's heroism took several weeks to reach my grandfather Jacob's tailor shop and home in the Frankford neighborhood of Philly. By the time my grandparents, my aunt and my father read of his exploits, Herman had already been killed. He died on Iwo Jima on March 6, 1945 at the age of 24. The family did not learn of his death until a telegram was delivered to their home on March 28. By then, the battle for Iwo Jima had been won. My uncle was one of 6,800 Marines who died at Iwo Jima, a battle which also claimed the lives of all but a few hundred of the 22,000 Japanese soldiers on the island.

The scrapbook was also filled with the many tributes to Herman in the days, weeks, and months following his death. Villanova, a Catholic university, held a special Mass in his honor. The Jewish War Veterans honored him by naming a Post after him and another fallen Jewish soldier from the Philadelphia area. Drizin-Weiss Post No. 215, located in Northeast Philadelphia, grew to be one of the largest and most active in the country. Each year, Villanova awards the "Chuck Drizin" award to a graduating athlete for dedication, loyalty, and unsung heroism.

Armed with the knowledge from the scrapbook, I searched the internet to locate any other information that could help me make the case for a medal of valor (Bronze Star, Silver Star, Navy Cross or Medal of Honor) for Herman. I found a reference to my uncle in an oral history given by Second Lieutenant Irvin Baker to representatives from Rutgers University, his alma mater, in 2000. In that interview, Baker told a story I had never heard before:

"I had a lot of friends who were lost. I had a particularly good friend by the name of Chuck Drizin, who went to Villanova College. His battalion was having a problem, and the commanding officer said, "We can't find out where their positions are. They can't find them from the air, and so, I need a volunteer to crawl back there at night, and determine where they are," and Chuck volunteered to do this, and he came back and he gave them these positions, and, I think, the very next day, he was killed."

Again, through an internet search, I located an Irvin Baker in Florida who was the approximate age of my uncle. I picked up the phone and called him. To my surprise, he answered. Now 93 years of age, Mr. Baker spoke glowingly of my uncle. The story he told spoke as much about his character as my uncle's.

Lt. Baker told me that he and "Chuck" met during training in the states and became fast friends. They went their separate ways until he had a chance meeting with my uncle on the streets of Honolulu just before they shipped out to Iwo Jima. My uncle invited him to a service on the beach led by the company's rabbi. At the beach, the two men made a pact -- if one survived and the other did not, the survivor would go to visit the family of the deceased. In 1946, after the war was over, Lt. Baker kept his promise. He went to that tailor shop in Frankford, met my grandparents, my aunt and uncle and told them about his admiration for Chuck. I had never heard this story before because my father, who had enlisted in the Army and was on his way to South Korea, was not present.

I called my Uncle Eddie, now 89, and he had no recollection of the meeting. However, he directed me to a second man who had served with my uncle, Private First Class Eugene Frederick. I called Mr. Frederick, now 88, at his home outside of Baltimore. PFC Frederick also spoke glowingly about my uncle -- "his Lieutenant" -- and said he was one of the finest men he had ever served under. I figured that PFC Frederick would have insight into my uncle's valor. He won a Navy Cross his heroism in taking out three Japanese tanks during the same battle in which the Philly papers noted my uncle's heroism.

Mr. Frederick, however, did not want to talk about the fierce fighting that took the lives of so many of his friends on Iwo Jima and could not tell me anything, in particular, about my uncle's bravery. He did, however, correct me when I referred to him as a "soldier." We are not soldiers, he told me, "we call ourselves Marines."

My uncle Eddie, convinced that Herman was the victim of anti-Semitism, would like me to file a next-of-kin application to seek a medal of valor for Herman. I've given it considerable thought. In my work representing men and women who have been wrongfully convicted, I understand the importance of righting past wrongs -- of re-writing history. And in the Jewish tradition, there is an obligation to do Tikkun Olam -- to repair the world. But I've decided not to seek posthumous honors for Uncle Herman. Here's why.

In looking at my uncle's life and speaking to men who knew him, I see someone who triumphed over anti-semitism, who played with and fought with and commanded Jews and non-Jews alike on the basketball court and the battlefield. He not only gained their respect, but their love and admiration. A Catholic university offered him a college education and a basketball scholarship and Villanova continues to honor his memory to this day. His Villanova basketball coach, the legendary Al Severance, also a non-Jew, travelled to a small synagogue in Frankford, donned a yarmulke, and eulogized Herman.

There are at least three men who named their sons after "Chuck", including my father who named my brother Robert after him, my uncle, and Chuck's best friend and fellow basketball star, Louis "Red" Klotz, who went on to a professional basketball career.

Herman lives in the blessed memory of all who knew him and served with him. My father, who died in 2007, spent his life honoring Herman and as long as I am alive, I will follow in my father's footsteps to keep Herman's memory alive. But perhaps the most persuasive reason not to seek these military honors is that I believe that my uncle, a true Marine, would not have wanted me to do so. If he were alive today, I think he would echo the words of Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, the Commander of the Pacific Forces, and remind me that in the battle of Iwo Jima, "uncommon valor was a common virtue."