Recently I was lucky enough to introduce a screening of the new documentary Marley on the life of reggae icon Bob Marley, at the wonderful Henry Miller Memorial Library in Big Sur, Calif. The "HML" has become the community center for that far-flung community, hosting films, musical performances by big-name bands who would never play a spot that holds only 300 people but who want to perform in the redwoods near the sea, and much more. There was an enthusiastic, almost-sellout all-ages crowd for this film showing under the stars and among the redwoods. This is what I could say...

At the end of "Billionaires' Row" in San Francisco, which is what the last two blocks of Broadway Street have been called, there are some stairs next to the last mansion where obsessive runners go up and down, ignoring the soaring views of the bay and mountains. It's pristine property -- some of the most expensive residential housing on the planet -- and there is only one little piece of graffiti there -- a stencil of Bob Marley. Whomever "tagged" that in such an incongruous spot must have had a sense of irony. But I also once saw the same image on the wall of an oasis at the edge of the Sahara desert.

Thirty-one years after his death, Bob Marley's image is everywhere, but in his lifetime he had some serious strikes against him. Born to a white father and black mother, he was of mixed race in a place where such people were accepted by neither "color." And he was poor, without a father present in a nation with the highest rate of "illegitimate' births in the world. And, once he was old enough to choose his own paths, he became a Rastafarian when that people of that faith were severely disdained by the mainstream.

What he accomplished in his short life of only 36 years is thus truly astonishing. From his earliest hearing of both American soul music, wafting across the Caribbean from Florida radio stations, and traditional Jamaican songs and drums at home in the small mountainous village where he was born, to his exposure to early Jamaican jazz-influenced music called ska in downtrodden Kingston where he emigrated, Marley soaked it all up and made it his own. His first songs were full of gospel and other early influences, sung by his Wailers trio with partners Peter Tosh and Bunny Wailer, wearing natty suits like their idols in Motown. In the late 1960s, the beat slowed down, the Rastafarian credo took hold, and by the early 1970s he was on his own, molding a crack band to play his uniquely complex and melodic songs. Selected as the great commercial hope for reggae by white recording industry insiders, he took on that role but made it his own, with few compromises. By the time he died of cancer in 1981, he was certainly one of the most famous and revered figures on the planet, not only for his signature sound but for his mostly uncompromised messages of struggle and hope. Among the less thoughtful his advocacy of cannabis seemed the most important message, but that was a sideshow (and as for white kids who took on dreadlocks, in a sort of stoned version of blackface, the less said the better -- but the man himself should not be judged by his followers).

As a California college student in the late 1970s, reggae was the primary part of my musical diet. The then-dominant disco and soft-rock of Fleetwood Mac, The Eagles, and such mostly bored me. Beyond the reggae musicians who had signed international recording contests -- the aforementioned Tosh, Wailer, and others like Toots and the Maytals, the Heptones, Lee Perry, The Mighty Diamonds, and some others -- reggae fans would have to seek out imported LPs to get our fix of that addictive rhythm. And when reggae bands came on tour, we were sure to be there. No matter that his message was often somewhat unclear to us -- it just felt right. There were eventual feelgood anthems among his songs with choruses like "Every little thing is gonna be all right" but then he'd sing "I feel like bombing a church/Now that I know the preacher is lying." This was not your usual boogie message.

Marley and the Wailers toured the U.S. a few times. They hit Santa Barbara a couple of times, giving legendarily fiery shows at the beautiful outdoor Santa Barbara County Bowl. The first time, my friends and I were able to walk up to the ticket counter at showtime and buy a $7.50 seat -- he had not even sold out the show, still being something of a cult favorite. A fledgling deejay for the campus radio station, I hustled an interview with Marley for the college radio station. To our shock, the band's management said yes, and even more shocking, the group drove over to campus, crammed into a station wagon, with no entourage or security, just a road manager who doubled as a driver.

Six or seven Rastas crammed into the little radio station studio. Marley sat down across from me. He was a short guy but exuded undeniable charisma, and was clearly the leader, even before he spoke a word. They were all wearing sunglasses and, true to form, most of them lit up reefers to smoke by themselves, like cigarettes (Rastas tended to share pipes, but less often a joint). It got cloudy in the studio fairly fast. I had the new LP playing on the turntable, to fade up and down in between questions and answers. It was a quick interview and was not easy as not only did they not seem to want to say much, but Marley would take many seconds to respond to my earnest queries -- and radio rule #1 was "No dead air." Having done some homework and read that Marley had said the SB Bowl was his favorite place to play in the nation (apparently due to that previous visit), I asked him why that was so. He just nodded, paused for a long time thoughtfully, leaned forward to the mic, and said "Welllll.... plenty good herb here!" A bit of hilarity ensued while I tried in vain to come up with a response. (I returned to the station years later to find a recording of this interview, and a later one I did with Peter Tosh, but of course those tapes had vanished; years later, working at the famous Reggae on the River festival in Northern California, I learned that reggae groups would often try to start their U.S. tours in California to stock up on local crops they could not bring into the country on their international flights).

On the way to the show later that afternoon, we stopped at one downtown's funky bars, a joint called The Sportsman's Lounge that opened at 6 a.m. for "Morning Bracer Hour." This early afternoon, there was a hard-looking guy among the regulars at the bar, and chatting with him over our beers, it turned out he was AWOL from Lompoc prison, an hour up the coast. "I don't care what it's gonna cost me, I've gotta see Marley," he said. He was a bit scary so we ditched him and headed uphill to the Bowl. From the first notes of "Positive Vibration," Marley and his band had the crowd enthralled. That show remains one of the few best I've ever seen, and is somewhat legendary among Marley aficionados. Lucky me.

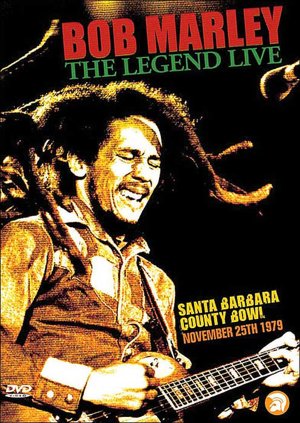

In 1979, they were touring in support of their new LP Survival, a militant return to form after some criticisms that their sound had gotten a bit "soft," with too many romantic songs -- a bit strange, that, given that their 1977 LP Exodus had plenty to say regarding poverty and Rasta themes, and has since been called "The Album of the Twentieth Century" by Time magazine). Now Marley was truly a worldwide superstar, and I had to get tickets ahead of time. I did not hesitate to blow off an old friend's wedding and a Rolling Stones concert down in Los Angeles (the Stones were already past their prime then anyway).

The show that evening was almost as intense as the previous one. Marley's band was bigger than ever and put out a huge chunky sound. In blue denim, he sang and whirled and bounced around the stage. The encore went on and on for many more songs. A few years ago this show was released on an official DVD for those who might want to see it; subsequent perspectives on Marley's career have tended to hold that he had already peaked and was tired on this tour, due to growing but still undiagnosed cancer; you can't tell from his energy at this show.

The next year he came through California on yet another tour -- one thing for sure, Marley was a hard-working taskmaster -- but there was something else going on that night and I figured, Well, not this year, he'll be back soon enough. Within a year he was dead. There's some sort of lesson there.

He died intestate, as they say, without a will as doing such planning for death offended his beliefs; and thus ensued decades of legal battles by his many heirs over the existing $100+ million and the revenue stream to come. Rolling Stone magazine just noted that his 'hits' CD Legend spikes in sales every fall when college students go off to campus; There are now Marley coffee brands, a tea called "Marley's Mellow Mood" which is full of soporific herbs; clothing lines, and on and one. Who knows what he might have made of all this, as he was legendarily casual, even indifferent, to his financial fortunes once he had enough to house and feed those he cared for.

Some of his kids have forged musical careers of their own, with varying success. I encountered some of them on tours when I was working backstage at musical festivals. One unit was called the "Ghetto Youth Crew"; I can't forget another reggae star, a contemporary and friend of Bob Marley, shaking his head at that moniker and saying "The only ghetto them youth ever seen is from a jet airplane!" Another star watched one of Marley's boys acting like a big star, with a bodyguard even, and lamented "If brother Bob were alive here right now, he'd have that boy over his knee." I titled one of my columns for a reggae magazine "The Bob Marley Workout: Just Spin in Your Grave" after reading of a daughter's wish to patent some sort of workout routine. But who knows. Maybe he'd just be a proud papa.

As for the new documentary, it's very good, and features some rare footage of Marley singing through tear gas at the show he did in the new nation of Zimbabwe to celebrate that nation's independence, plus interviews with previously unheard-from childhood friends and relatives, including those related to his long-lost father in Britain. It's something of a "warts and all" portrait, as some of his kids express lasting bitterness about their absent dad, and some of the many women in his life seem to wish he had been a bit less promiscuous -- even though that might have meant he would not have known them, and some of those kids might not exist. The film could have used more footage of his burning performances, to drive home what the legend is all about -- the music. But his was a singular, inspiring, disturbing, tragic, but in the end triumphant life.

Long may he sing.