I read a great piece in the Washington Post about philanthropy's quick response ($348 million) to the Ebola crisis.

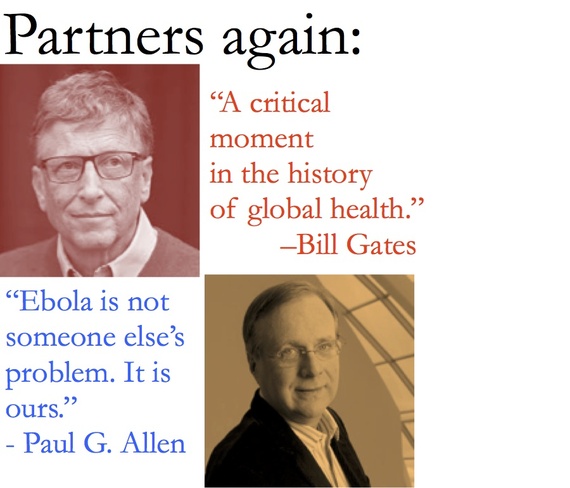

Kudos to the Paul G. Allen Family Foundation, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Mark Zuckerberg and his wife Priscilla Chan, who, among other donors, have responded not just to the immediate demands of a growing crisis, but with investments in research and system capacity. The ability of philanthropists to collaborate with government, NGOs and each other - as well as release money quickly - has been admirable.

Yet, the need for philanthropic support to confront Ebola in Africa remains acute. So, what can philanthropists do?

Here are ten ideas to consider:

1. BE QUICK, BUT DON'T HURRY

Legendary UCLA basketball coach John Wooden used this phrase often to characterize an approach that combined readiness and responsiveness with good judgment. Solid research, cogent analysis and the ability to say no to a poorly thought-out proposal are all hallmarks of good crisis giving. It's natural to feel an emotional pull to take action. But the impact of any action will be enhanced by taking time to learn the specifics of a disaster.

2. WASTE NOT

The stories of misdirected emergency aid are as common as they are painful. Because desperately needed medicine is labeled in a foreign language, it lies unused on the docks. Tons of donated food cannot be distributed because there is no security to ensure delivery. Truckloads of unneeded clothing arrive at the site of a flood due to early and erroneous media reports. Low priority aid can clog transport, storage and distribution and slow urgently needed supplies. Donors should keep in mind that cash grants are often much more useful than goods unless those goods come in response to a specific and credible request. And grants designated for general operating support can provide much needed flexibility and stability during times of crisis.

3. REACH OUT TO COMMUNICATE

Information is king during a disaster. But initial news reports can be misleading. Disasters can destroy communications infrastructure.

National or international media reports about needs in affected areas can be untrustworthy and governments can skew the official story to serve political ends. Since needs often change dramatically from day to day, week to week, even established and authoritative sources may simply not know the real needs of the people and communities affected. Updates should come from trusted local sources and informants. This is where two-way communication is important. Donors need not wait passively for information to come to them. They can be active in seeking out local partners and NGOs already working in the crisis zone, not only to find out what is going on and what people need, but to ask if their ideas for philanthropic support might be useful.

4. COLLABORATE

This can be difficult and costly, but there are glaring penalties for lack of collaboration during crisis. Duplication, waste and poor prioritizing are among the pitfalls for funders who don't work well with others. It's worth remembering that philanthropy can play a unifying role in these situations, bringing together key actors across sectors. Philanthropists also can work with peers to pool funds and share information - as Gates and Allen have to respond to Ebola. A key strategy for funders is sharing information with other donors. In times of disaster, complex grantmaking processes and strict guidelines become less important than reaching out quickly to affected communities.

5. CONSIDER THE LONGER TERM

Communities recover over many years and yet crisis philanthropy often focuses only on the short term.

"More than one-third of private giving is typically done within the first four weeks of a rapid-onset disaster, and close to two-thirds within the first two months," according to a 2011 report by the Conrad N. Hilton Foundation. "Within five or six months, almost all of this giving stops."

Yet, the best role for philanthropists may not be as first responders. Sending the vast majority of resources into the disaster area in the very early stages can have significant drawbacks. Often, an effective approach is to split funding -- initially supporting the capacity of groups that are already mobilized and deferring part of a grant for weeks or months to see what important needs remain after the first wave of relief aid.

One of the best ways to support long-term recovery of affected communities is by giving residents tools and opportunities to help themselves. When communities come together and neighbors help neighbors, it can prove more effective in generating resiliency than when people from outside the community come in to provide services and then leave.

6. TURN YOUR EXPERIENCE INTO USABLE INFORMATION

Lessons from one crisis can inform the response to the next. Funders who record their strategy and their outcomes -- their challenges as well as their successes -- add to a knowledge bank for other organizations. When such stories are made accessible to other funders, NGOs and governmental agencies, the ability to respond to the next crisis is enhanced.

7. INCREASE IMPACT BY BEING FLEXIBLE

Consider doing things differently in light of a particular crisis. Is there a local nonprofit organization that has not received a large amount of philanthropic support in the past, but is doing a great job now? Can grantmaking processes be streamlined? Is there an area you don't normally fund, but which you can see represents a pressing need? The ability to improvise can prove valuable as the crisis changes over time.

8. DO YOUR DUE DILIGENCE

Many philanthropists wonder if they should give money to a big organization like the Red Cross in response to a crisis or if they should try to keep within the framework they've built for funding smaller organizations. There is no simple answer. Support to major aid organizations is vital. At the same time, philanthropists should keep in mind that big international relief organizations sometimes receive more contributions for a specific disaster than they can spend. There may be organizations you already know working to help affected populations whose response efforts you could support. These trusted partners may also be a valuable source of useful information.

9. KEEP YOUR FOCUS

Disaster-related grants can fit into a funder's existing programmatic or geographic priorities. For example, a foundation with a program focused on youth can target its disaster response grants to help school programs expand to include affected children.

10. PREPARE FOR THE NEXT CRISIS

Emergencies don't eliminate the need for planning and strategy, they heighten it. The trick is not to wait until the emergency is upon you. Some donors create their own crisis plan with specific roles for staff or consultants and specialized resources. In developing guidelines, consider:

TIMING- Where in the recovery stage do you fit in?

DECISION MAKING - Who in your family or on your staff is designated as the lead person to manage an efficient response?

FOCUS - To what types of crisis will you respond? What target areas or populations will you support?

PARTNERS - Is there a short list of donors you might collaborate with?

PROCESS - Is there an established vehicle for giving? Are there streamlined grantmaking processes in place for such situations?

Update your disaster plans periodically to ensure they stay up-to-date with your philanthropic interests.

FOR MORE: An online guide on the subject from Rockefeller Philanthropy Advisors - Giving Strategically After a Disaster

Cross-posted on Thinking Philanthropy.