A combination of Thanksgiving and Easter. That's the way photographer Natalie Fobes describes celebrations honoring the first salmon caught of the season. Read below about Fobes' 10 year photographic odyssey following Pacific salmon. Here, Raymond Moses tunes his drum before the Tulalip First Salmon ceremony in Washington state. (C) Natalie Fobes.

Natalie Fobes says photography has given her a "passport to experience" that few ever receive.

And for more than 30 years, she's made the most of it, creating an itinerary of adventures that is both admirable and eclectic. A few highlights:

- Her photos of the Exxon Valdez oil disaster became a cover story for National Geographic Magazine in 1990.

- She lived with Chukchi reindeer herders in Siberia, documenting their lives in harsh conditions.

- With her husband Scott Sunde, an editor at the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, she adopted two orphan girls from China, starting a very personal documentary project as a mother/photographer.

Sacrifice and Re-birth with the Salmon

More on those other stories shortly. First, I want to delve into what Fobes once called her "obsession" -- photographing salmon in the Pacific region and telling the story of their cultural importance to Pacific people.

In an interview before her Iris Lecture in February at the Annenberg Space for Photography, she said the salmon project brought her life meaning during a time when she faced great personal loss.

"It was a 10 year project. It bridged the gap between my newspaper career and my magazine career. But more than that it taught me a lot about life. During that time, both my brothers died of alcoholism, my father died of cancer and my mom was pretty sick. My dog died. There was a lot of loss during that time. But the salmon project was always a constant in my life. And so that was something that helped me get through the difficulties."

National Geographic rejected proposals from Fobes three times before finally giving her a chance. She wanted to do a holistic look at salmon -- not just their importance to fishing and the environment, but their cultural significance.

Fobes: One of the things that really struck me was that the Native Americans and Canadians have this wonderful relationship with the salmon. They feel it is a gift from the Creator. And the salmon return each year to sacrifice themselves so that mankind can survive, and with that great gift is a demand that the native peoples have respect for the salmon and treat the salmon with great dignity. And so the first fish caught is celebrated [First Salmon Ceremony] and it's kind of a cross between Thanksgiving and Easter. It's thanking the Creator for this gift and also a rebirth, a feeling of great rejoicing in living.

Me: Sounds like it was part of a culture of very early sustainability as well as being of cultural and mythical significance.

Fobes: Exactly. If they took too many fish then the salmon would not return. And they knew that. Some tribes would close off fishing for three days a week or only every other day. But they definitely had a good way of managing the resource.

On the Klickitat, a tributary of the Columbia River in Washington. A Yakima man fishes for Chinook salmon with a net attached to a long pole, the way his ancestors did when Lewis and Clark came calling in 1805. In her Annenberg talk, Fobes recounted a Yakima story about the visit of the explorers. According to the story, the expedition was greeted with a celebration and offered a feast of freshly cooked salmon. But Lewis and Clark's party declined the offer, instead pointing to the tribe's dogs, indicating they would like to eat them. The villagers did not understand. But it turns out the salmon had some parasites that disrupted the digestion of the explorers. Every time they ate salmon, "they had the trots," said Fobes. No wonder they preferred dog meat. @ Natalie Fobes

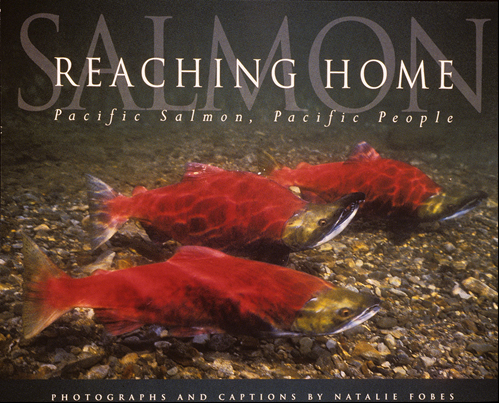

Over the decade of work on the project, Fobes was nominated for a Pulitzer for her writing about salmon, she took photographs for a National Geographic article about the Pacific Salmon and co-authored a book -- with Tom Jay and Bradford Matsen -- Reaching Home: Pacific Salmon, Pacific People.

The book was the culmination of a project that began when she visited a salmon stream with her father.

"At first I couldn't see any thing. I looked into the water and there was nothing. And then I saw a fin move out of the water so I started paying more attention. Then all of a sudden this sockeye salmon came leaping out of the water and hung there in the afternoon light. It was amazing. I was overwhelmed with emotion. I was excited. I was sad. I was melancholy and I was in awe. All at the same time. And all of the time that I was experiencing these emotions, there was a little voice in me saying - it's just a fish . It's just a fish.

"It finally went back in the water. I turned to my dad -- my face was open and full --to see if he had seen the salmon leap. And in my dad's eyes there was a look that I had not seen before. And I realized he was crying. Now my dad was not what you'd call a treehugger. My dad was a farmer's son , a fisherman, a hunter. And yet there was something about seeing that salmon leap that caused him to cry. And at that point I decided I wanted to find out what it was about the salmon."

In the Beginning

Natalie Fobes owes her 33-year career of photography and adventure to a college professor who insisted she do something she really did not want to do -- take photos of people.

"I was very shy and I liked to photograph buildings but could not stand the thought of photographing people. Just scared the heck out of me."

The first woman she photographed ended up inviting her into the house for a chat. Fobes learned the woman had come to Iowa in a covered wagon. The woman had led a difficult life -- with uncertain income from the family farm and personal tragedy -- she bore five children and buried three. As Fobes listened, she realized she had been granted a great privilege and her whole perspective on photographing people changed.

"I realized the passport to experience that all photographers carry and with it we are able to experience things that few people experience."

A Person With a Camera, Not a Camera With a Person

Now interactions with people are her favorite part of the job.

"Now that I've gotten over not liking people [she laughs] ... I love meeting people. I love walking in different cultures. Experiencing different lives... When I started shooting people it gave me an opportunity to go up and introduce myself. I would take a photograph of them and come up and ask them a bit more about their life. I've got to admit that once, when I was young and single, I used it to meet a couple guys. [more laughter] I don't do that any more...

"The flip side of that is that in some cultures where people aren't used to having that [the camera] around, I'm thinking of the Kechi [in Guatemala], or when I first went to Russia right after it opened up or when I went to Vietnam right after it opened up, that it kind of got in the way. There was a camera and people in front of the camera. Took a lot of time to get people to relax and get used to me as a person with a camera, instead of a camera with a person behind it. "

"How the Hell Are They Going to Clean This Up"

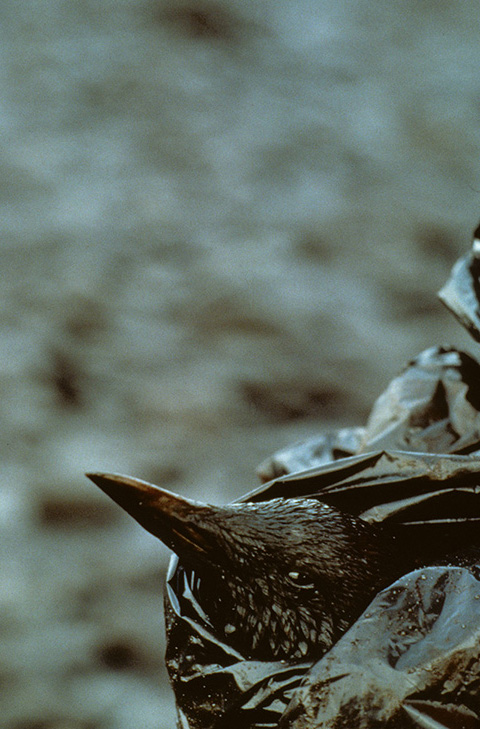

Prince William Sound, Alaska. One of hundreds of thousands of animals affected by the 1989 Exxon Valdez oil spill, this blackened bird became an icon of environmental disaster when National Geographic ran the photograph on its cover. Fobes says 350,000 birds and 1,000 sea otters died after the supertanker ran aground, releasing enough oil to cover 2,100 kilometers of coastline. (c) Natalie Fobes

"Got my first look at the spill. I can't believe it. The fumes are nauseating as we flew at 1500 feet. Even at this altitude I can't see the edge of the spill. How in the hell are they going to clean this up." --Excerpt from Natalie's journal (March 25, 1989) as posted on her website.

For three months, Fobes shot the deadliest oil spill in North American history -- and the biggest until last year's BP Deep Horizon disaster in the Gulf. She travelled from Prince William Sound to Kodiak Island to the Aleutian Islands.

"I was one of the very first photographers to arrive on the scene. I arrived the day after the spill... I didn't have daily deadlines. So I was able to get out with the fishing boats and out with the cleanup boats and out with the Coast Guard and the Navy and out with Exxon. And I could spend days out there - just traveling from boat to boat. From plane to plane. From beach to beach. Getting my coverage. It was a logistical nightmare because there were no ways out to the spill from Valdez. All of the planes and helicopters were chartered by either Exxon, the Coast Guard or the government. Or the networks. So that's where my experience with knowing how to be on a fishing boat and how to hitchhike from boat to boat came in handy. "

Exhausted and covered with the oil they had been trying to clean up, a crew returns from Eleanor Island. (c) Natalie Fobes

Siberian Adventure

This Chukchi reindeer herder's face was the first thing Fobes saw after a 28-hour traveling ordeal. She was working in Siberia on a National Geographic story about the Bering Sea region. She set off to visit the Chukchi village on Russia's Chukotka Pennisula on a tractor vehicle -- the main means of transportation in that part of the world. She had to ride in the back in a dark cargo section much of the journey. Up in the front, the driver had room for only one passenger in addition to his home brew. Part of the way through the long trip, the tractor vehicle fell into a hole -- because the driver had got lost -- while drinking the home brew. Finally, after a bitterly cold night, and more than a full day after the journey began, the tractor stopped and the hatch opened. "And I see this man, dressed from head to toe in skins, his face covered with snow and I thought I was hallucinating," said Fobes. (c) Natalie Fobes.

She wasn't. Hallucinating, that is. The herder took them immediately to see his herd. Fobes went from sleep-deprived and miserable to a state of wonderment.

"During the wintertime they take the herd from place to place ... so the herd can scavenge for the lichen that's just under the snow. [There were] over a thousand of these animals and about six men that would herd them. While I was there they harvested one of the reindeer and this was the first time that I saw them use everything on that animal. They used the intestines for sausages. They used the stomach for water vessels and liquid carriers . They used the tendons for sewing together the skins. And the skins they used for their clothing and also for their portable tents that they would transport as they moved from pasture to pasture. It was an amazing time for me to live with these people as they had been living for over 500 years. I loved being there and watching."

Chukotka Pennisula, Russia. "The things that I photograph today will be there long after I'm gone," Fobes told me. "And a lot of the work I've done - the edgy stuff - the experiences that few people have had -- I went into them with that feeling of history, that I am recording an event that will not be the same in a year or in ten years. The Chukchi herd their reindeer differently now. They've become a little more modern after 500- 600 years of doing it the same way... So the photographs that I have of those people probably couldn't be replicated now. That feeling of history is really important to me." (c) Natalie Fobes

The Hardest Part

I asked Fobes what she liked least about photography. For the former shy undergrad, who once preferred focusing on architecture rather than people, she had an interesting answer.

"Saying goodbye to the people I've met... When you've experienced things with them, when they've allowed you to step into their lives and opened up to you and then to leave... it's very difficult... There are very few people I don't like in this world. Once I've spent the time with them, then it's hard. It's like leaving a friend and knowing you'll never see them again."

One of those people can be seen in the Polaroid image below. A small town doctor from Siberia, she befriended Fobes after her time with the reindeer herders.

"That is me after 17 days with no bath or shower," says Fobes. "Poor woman. "

Fobes elaborates further in this video excerpt from her lecture in Los Angeles.

(The entire lecture can viewed on the Annenberg Space for Photography website. )

Stories That Need to be Told

Fobes says her photography is built on two principles:

- "Be true to your subject. Don't go into a story with pre-conceived ideas or a slant. Let them tell the story. Try to get all sides of the story."

With this "professional mission," as Fobes calls it, it' not surprising that she decided to start a nonprofit 15 years ago with two colleagues, Phil Borges and Malcolm Edwards. Called Blue Earth Alliance, the nonprofit aims "to help photographers do documentary projects about stories that need to be told." Fobes says that the 501 c3 has sponsored more than 100 projects over the years and helped photographers raise nearly a million dollars to fund their work.

Personal Documentary Project -- Motherhood

Phoebe and Ginny (c) Natalie Fobes.

Nine years ago Fobes and her husband traveled to China to pick up their daughter Ginny. Two years later, they were back. "We had so much fun with Ginny, we went back to get Phoebe," says Fobes.

The photographer sees her parenthood as directly related to Chinese history.

"[The adoptions] were an unexpected consequence of China's one child policy. They started the policy in the 1970s to counter-effect the exploding population. They knew they would not have enough food to feed all their people. So they implemented this one child policy. Traditionally in Chinese society the boys are the ones who take care of their parents and so often the girls are abandoned.

No one outside the Chinese government knows exactly how many girls are abandoned each year or how many children are adopted each year, but in some of the provinces the ratio of boys to girls is dramatically higher than it should be. [It' gotten] to the point that now the government is embarking on an education campaign to talk about how important girls are to their future and how wonderful girls are. The government is concerned that by 2040 there will be a shortage of girls. Some estimates say there will be 200 million men who won't find women to marry. Already there are instances of women being kidnapped and brought in from other countries."

Back home in Washington, motherhood triggered a time of creativity for Fobes -- as she wrote a novel, music and found photographic adventures close to home.

"I became amazed at how the brain developed and the physical aspects of growing... I had an incredible spurt of creativity that came just after Ginny came home ... I think it was more marveling at the wonder of life that watching her develop created inside of me."

Since then, Fobes has traveled less and sought projects in the Seattle area -- shooting weddings and other local subjects. This year, she's teaching a video course on the foundations of photography called "Color, Composition and Light" for the photography website lynda.com. This job comes after being the subject of one of lynda.com's Creative Inspiration documentaries.

But no matter where Fobes is shooting, she's always looking to "show people what they may not see for themselves."

"Sometimes life moves too quickly. You're looking and things are moving along, it's too fast for you to hold on to. But when a still image comes across and captures you , that gives you time to look at it, really examine it, to figure out really what is going on in that situation and then maybe act on it or apply it to your own life."

(c) Natalie Fobes

Disclosure: The Huffington Post is a sponsor of the current exhibition running at the Annenberg Space for Photography -- "Extreme Exposure."