Once again a mass shooting that left 14 dead and 21 wounded on Wednesday in San Bernardino, Calif. is sparking public outcry against gun violence in this country. Within hours of the shooting, the perennial debate over guns in American society began to circulate on news outlets and social media. This discourse varied widely, ranging from comparisons of gun control between the United States and other industrialized nations to an accounting of the number of mass shootings that have occurred in the U.S. in 2015.

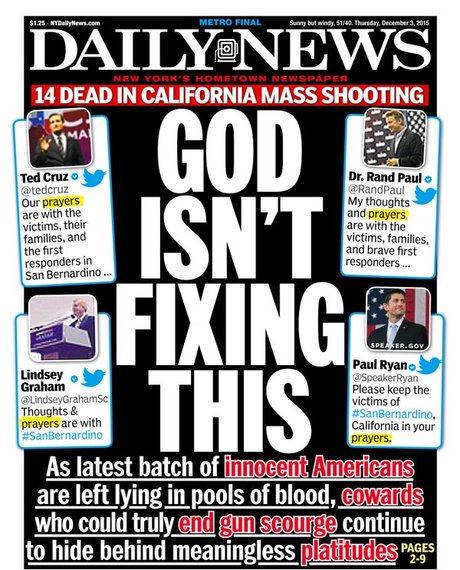

Common to this discourse is the persistent public frustration over increasing gun violence and the lack of political action on gun control. This frustration was encapsulated and embodied on the front page of the New York Daily News rebuking politicians who offered "meaningless platitudes" in the form of prayer after the shooting. For the tabloid, "thoughts and prayers" aren't enough and political inaction is equated with "God isn't fixing it." By day's end on Wednesday, the Daily News cover became viral and was shared over 22,000 times on Twitter. For many Americans, the front page precisely expressed how they felt about gun control as well as the need for a national dialog on gun violence. Sharing the Daily News cover via social media became the public's way of venting outrage and exasperation at this intractable issue.

The Daily News front page did not sit well with some. The following day, calling the newspaper's cover "prayer shaming," several religious leaders critiqued the tabloid's gross misunderstanding of prayer. Writing in the National Catholic Review, Father James Martin calls the cover "ridiculous and insensitive" and contends prayer is a form of action since "The disgust and anger and sadness that we feel over these kinds of violent acts are precisely God's disgust and anger and sadness. This is God inspiring us, urging us, begging us to act." Religion News Service reporter and columnist Jonathan Merritt argues "A life of faith is a life of prayer and action, but never one without the other. Action without prayer is merely activism, and prayer without action is useless piety." Russell Moore, president of the Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission of the Southern Baptist Convention, writes "For religious people, of all sorts, prayer is doing something. We do believe that God can intervene, to comfort the hurting and even to energize ourselves and others for right action."

Is "prayer shaming" merely about the effectiveness of prayer and the kinds of actions it can engender for those who practice it? This contention over prayer and politicians who practice it (or at least those who tweeted that they "prayed" after hearing about the San Bernardino shooting) is really about the role of prayer in American public life and whether religion has a place in informing debates such as gun control in American society.

It's instructive to read Moore's words on this issue. In the same Washington Post column, he suggests that prayer is an activity that both the religious and secular practice, that

"Hashtag activism has become, in many ways, our new secularized form of praying. The expressing of one's opinion is a way to say, 'I'm the sort of person who wants to restrict guns' or 'I'm the sort of person who wants to racially profile Muslims' or 'I'm the sort of person who wants more resources for police.'

"But let's be clear: that's not 'doing something.' It is one more indication that politics has become more than just politics. It's become a kind of secularized religion -- with its own sets of orthodoxies, denominational distinctives, and rigorous forms of excommunication (the 'block' button on Twitter).

"It shouldn't be this way. The first response to a word of our fellow citizens in peril should be a human response of empathy. For religious people, that means a call to pray for them, and to encourage others of like mind to do so."

Moore equates "hashtag activism" as a ritual practice associated with secularized religion because. For Moore, what is religious and secular are really two sides of the same coin. At some level, Moore argues, all of us are religious. But while secular practices merely offer wishful thinking, Moore suggests prayers offered from a religious orientation comfort and allow us to identity with those who are suffering. Prayer makes us human, and it should be practiced in public because it has implications for public life in America. If "prayer shaming" is allowed, it amounts to an attack on religion and practitioners will keep prayers private. Prayers that are public can shape public discourse, resulting in a common good and produces civility that is sorely needed in the current political climate. What Moore and other religious leaders are saying by critiquing "prayer shaming" is that religion still has a place in American public life, and that religion can inform how we act and treat each other as fellow citizens.

But if this is so, then what about those politicians who offered prayers for the victims of the shooting? If they invoke religion and profess to be religious, shouldn't they be judged by their words and also their (in)actions? If Jonathan Merritt is correct in saying that a life of faith is both a life of prayer and action, then the American public should and must expect and demand their political leaders who profess faith to talk, live, and act in such a way that does not demonstrate a "useless piety."