There is no subject discussed more often in the Bible than that of the "stranger." For Jews, remembering our outsider and previously-subjugated status is so central that we not only recite the story of the liberation from Egypt during Passover, we also chant it every Friday night as part of the prayer over the wine: "You shall not oppress a stranger, for you know the feelings of the stranger, having yourselves been strangers in the land of Egypt." (Exodus 23:9)

Importantly, the Torah goes much further than merely saying we must accept and not oppress outsiders; it commands "And you shall love the stranger..." (Deut. 10:19) Love them? Really?! That's a command much easier said than done. (Eg.: See "Ground Zero Mosque" reactions.) But, it's an edict that's paramount to creating genuine empathy, the sentiment that's most essential in shaping ethical behavior.

So, when I recently participated in a leadership development program that required me to craft some sort of "Experience as Other," I concluded that as a Jew in Texas, perhaps the most "other" I could experience would be to exist as a Muslim Arab in post 9/11 America. Below is what transpired.

On the fateful morning, I awoke -- and despite my wife's profound confusion and consternation -- I donned traditional garb of an abaya and kaffiyah, a robe and headdress. I began by driving to the El Farouq Islamic Center for morning prayers. However, because I had misread the schedule, by the time I arrived, nobody remained except for an older gentleman mopping the floors. But the miscue proved valuable.

The cleaning man greeted me: "As-salaam alaykum."

"Wa alaykum as-salaam," I responded.

He smiled and continued cleaning. So I took off my sandals and entered the empty worship space. As I walked around the book-lined room, feeling the soft carpet beneath my bare feet, I began to breathe more slowly and more deeply. I stopped, sat in the midst of this mosque in far west Houston, and tried to truly actualize this odd, out-of-body encounter as my own. . . .

My next stop was Hobby Airport, where I planned to board a flight to Dallas. As I made my way to the ticket counter, I noticed those noticing me. And for the first time in my life, I was nervous about going through security. What would the T.S.A. folks think and do? I figured I had to be completely compliant and not dare show any impatience, no matter what transpired. In fact, they were quite cordial - though a foil gum wrapper trapped deep in my robe pocket did lead to a special hand-check. Still, I felt a strange sense of relief as I was allowed to proceed towards my gate.

In order to maximize the experience, (and since I was flying Southwest), I waited until shortly before take-off to board the plane. As I slowly walked down the aisle looking for an available seat, I scanned a sea of faces that looked up, took note, and quickly turned away -- as if hoping that by avoiding prolonged eye contact, I would continue on my way. I settled in the very back. Once airborne, I pulled out an English-version Koran I had brought with me. As I sipped black coffee and read suras (verses) that seemed oddly obsessed with Jews, I felt this powerful disconnect between what I was feeling internally -- Why must Islam care so much about us? -- and how I assumed I was being perceived externally. I also wondered about the couple next to me. They wore football jerseys and seemed, well, unusually Texan -- so I decided to make conversation. Feigning my best Middle East accent, I asked them where they were from and what they did for a living. Initially caught off guard, the husband and wife quickly warmed and asked about me. "My name is" -- What was my name?! - "Salhad Din," I answered. "I am from Saudi Arabia and here on business."

Once on the ground in Dallas, the disconnect I felt on the plane reading the Muslim holy text became even more pronounced. The President of Iran was speaking live on CNN. I crowded close to the television in order to read the translation of his hateful words. At that very moment, Ahmadinijad was "explaining" his denial of the Holocaust. I was disgusted -- at the man and at Columbia University for providing him such a public platform. But as I turned away, I once again wondered: What did those watching me watch him think? In fairness, I was projecting -- I had no idea what, if anything, those around me were thinking. Still, I couldn't help but notice the constricted sense of self that had descended on me just playing the role. In fact, when waiting for the return flight to Houston, I sat next to a good-looking, well-dressed woman who chatted flirtatiously with a few guys around her; I wanted to join, but felt an unusual hesitancy about even trying to participate. Whether self-imposed or not, I felt a very real barrier between us. So I simply continued looking down, as the kaffiyah fell forward and covered my eyes.

Back in Houston, I was leaving the airport and no longer "in character" -- I had stopped speaking in an accent and taken off the headdress-- when the cashier asked me if I was a Muslim. Apparently, he had noticed my robe. "I see you're dressed for Ramadan," he commented. He then introduced himself as Muhammed, a recent immigrant from Ethiopia, and told me of the occasional prejudice he faced in our country. "I'm sorry," I offered, "I'm really sorry. Have an easy fast."

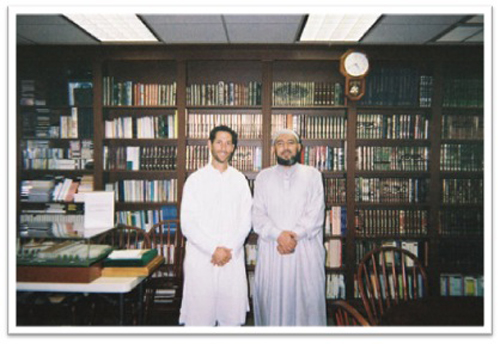

My afternoon ended where my morning had begun--at El Farouq. But this time, there were several people there. I explained to some what I had been doing; others assumed I was a new member of the mosque. They invited me to pray with them, which I did. It was a fitting conclusion to a day of unusual spirituality. As Jonathan Sacks, Chief Rabbi of Great Britain, wrote in The Dignity of Difference: "We encounter God in the face of the stranger. That is, I believe, the Hebrew Bible's single greatest and most counter-intuitive contribution to ethics...The human other is a trace of the Divine Other. As an ancient Jewish teaching puts it, 'When a human being makes many coins in the same mint, they all come out the same. God makes every person in the same image -- God's image, and yet each one is different.' The supreme religious challenge is to see God's image in one who is not in our image."