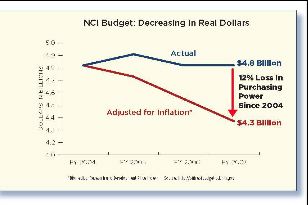

Few issues enjoy as much bipartisan support as America's long-running "war on cancer," as President Nixon put it in 1971. But political rhetoric hasn't been reflected in congressional action. Funding for cancer research has remained flat since 2004 -- and has fallen significantly after adjusting for inflation, according to the Biomedical Research and Development Price Index, Office of the Budget, National Institutes of Health.

In recent years, the NCI's ability to fund cancer research has been severely restricted.

President Obama has vowed to make significant changes. The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (Recovery Act) signed into law by President Obama on February 17, 2009 includes an unprecedented boost of $10.4 billion to the National Institutes of Health (NIH). $1.26 billion from the stimulus is designated for the National Cancer Institute (NCI). The stimulus package plus the permanent budget of NCI increases the number from $4.95 billion in 2008 to nearly $6 billion for FY2009.

But the one-time boost aims to improve the outcomes for cancer patients while jump-starting our economy and creating or saving jobs. Stimulus dollars have to be spent before the end of FY2010 and must not be commingled with appropriated funds. Cancer researchers, although grateful, say what's needed is a sharply increased, long-term financial commitment without the shackles of job creation, spending deadlines and separate accounting for federal funding. Meanwhile, an estimated 565,000 Americans are dying each year from various forms of cancer, according to the American Cancer Society.

Cautious Enthusiasm

"The [stimulus] package conveys two years of funding, which in laboratory science is a relatively short amount of time," said NCI Director Dr. John Niederhuber speaking to a group of physician-scientists at the 100th annual meeting of the American Association of Cancer Researchers (AACR) in Denver, Colo. in April. "We must hasten our progress against cancer by conducting exciting new science...Economic stimulus funds give us the chance to be visionary."

"The Recovery Act has energized people towards science," said Olufunmilayo (Oh-Luh-fuhn-ME-Leye-Oh) I. Olopade, (Oh-Lah-Pa-dee), professor of medicine and human genetics and director of the Cancer Risk Clinic at the University of Chicago.

"In the last four or five years, it's been so depressing thinking about ideas knowing that there's no way you are going to get this [grant request] through," said Olopade. "The fact that you have everyone engaged, the fact that people are coming together, writing proposals, no matter how many people are funded, [the increased budget] has recharged the scientific community."

The NIH will support many types of funding, but, in general, it will focus scientific activities on: "shovel ready," recently peer-reviewed and new, highly meritorious requests for funding capable of making significant advances with a two-year grant; Projects that accelerate the tempo of ongoing science through targeted supplements to current grants. Supporting new types of activities that fit into the structure of the Recovery Act, including a reasonable number of awards to jump start a new NIH Challenge Grant program where progress can be expected in two years.

Challenge Grants

NIH anticipates funding 200 or more challenge grants, each one up to $1 million in total costs, depending upon the number and quality of applications and availability of funds. Despite claims among scientists at the annual meeting in Denver that submissions were in excess of 40,000 a week before the April 27 deadline, "NIH received 14,000 challenge grant applications of which 1,200 were for NCI," said Michael J. Miller, senior science writer and NCI press officer by e-mail.

As to the likelihood of being funded for the first round, "You have to keep trying and not worry, said Greg Karczmar , PhD, a professor of Radiology and collaborator of Dr. Olopade's at The University of Chicago Medical Center. "You figure after 20 or 30 applications go out the door, some money will come back," he said. "It becomes a very inefficient cycle."

Forfeiting an opportunity or sending your grants out the door without real pressure may be one thing for a senior investigator whose lab and reputation are already established. For younger investigators, worrying about limited research dollars is part of the daily grind.

"There was a frenzy of activity trying to get grants out in time for the April 27 deadline," said Daniel Catenacci, MD, 33, a hematology/oncology fellow at the University of Chicago Medical Center. He attached his name to two grant applications.

To receive his own grant, Dr. Catenacci said, "would help launch my career." Working with a mentor, he would execute clinical and pre-clinical trials in pancreatic cancer (working with animals in advance of humans) in the hope of discovering a suitable drug to combat the deadly disease.

Of his challenge grant chances for success, Dr. Catenacci said, "I am not holding my breath or putting all my eggs in one basket. I will still be applying to many other grants this year...in order to get my research funded." These include a Mentored Clinical Scientist Development Award from the National Cancer Institute and an American Society of Clinical Oncologists Career Development Award.

Six week after his application deadline, Dr. Catenacci's application for an ARRA (American Research and Recovery Act) grant was approved. "We are very, very happy!" he wrote by email.

Like many investigators who work collaboratively, in addition to federal funding, the University of Chicago, drug companies, philanthropies and other government agencies support Dr. Catenacci's research program.

"This [the one time infusion of cash] will allow a larger than usual percentage of young investigators to get grants," said Robert A. Weinberg, PhD, a Founding Member of the Whitehead Institute at Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He is most widely known for his discoveries of the first human oncogene -- a gene that causes normal cells to form tumors.

"It's too early to say whether this funding provides a firm launching pad for their research careers," said Dr. Weinberg, "or a cruel hoax deluding them into believing that they will be able to support their labs when the money dries up in 2010."

A Funny Way to Think About Cancer

Assuming researchers can make sense of the litany of rules, regulations, maintain transparency and accountability as required, it is estimated that the two-year stimulus money will add or retain six to seven jobs for every grant funded, according to a 2008 NIH study. The goal is to maintain those jobs after the stimulus funding expires, but that, of course, will depend on how Congress and the president allocate future federal budgets. More jobs or not, Americans "want better ways to prevent cancer, they want the earliest diagnosis; and they want new therapies with fewer side effects that turn cancer into a condition you can live with and not die from," said Dr. Niederhuber when he spoke in Denver.

Sustained Funding

"The stimulus funding will not help ensure the long-term viability of our research system," said Dr. Richard L. Schilsky, president of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), in testimony before the Subcommittee on Labor, Health and Human Services, Education & Related Agencies, House of Representatives Committee on Appropriations.

"The people necessary to do the work and the underlying infrastructure are at critical break points, and have been endangered by a failure to keep pace with the growing costs of conducting research and a lack of predictable funding for National Institutes of Health (NIH) and National Cancer Institute (NCI)," said Dr. Schilsky." Losses have delayed the quest for new cures, demoralized the research workforce, and left us with few options to buttress a starving infrastructure that can no longer rely on clinical margins to counterbalance inadequacies in research dollars."

"We must demonstrate that NCI is worthy of sustained, increased support for years to come," said Dr. Niederhuber. "For just that reason, it falls to NCI to carefully calculate and thoughtfully assume the risks of initially funding some four-year grants with economic stimulus money, knowing that we will need to find additional resources for the out years."

Investment in Cancer Research at a Turning Point

President Obama, speaking to a joint session in Congress on February 24 said the economic stimulus package he signed "will launch a new effort to conquer a disease that has touched the life of nearly every American, including me, by seeking a cure for cancer in our time."

"We are not likely to have one cure for cancer," said Nobel Laureate Harold Varmus, President of Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York City and one of three co-chairs of President Obama's Council of Advisors on Science and Technology who appeared on The Daily Show. "We are going to have cures for many different kinds of cancers; a collection of diseases."

"Paying attention to cancer is important," said Dr. Varmus but "doing basic science and learning how things work," have led to some of the most important scientific advances in our time. He cited the Human Genome Project which came to be through basic research in chemistry.

"Science does depend upon the political process," he said. "We get our money from the government, the government is representing people. People care about diseases."

"What's awkward," said Dr. Varmus, "is when the demands are in excess of the opportunities to do useful science."

Senator Arlen Specter, the Pennsylvania Republican-turned-Democrat and a survivor of two rounds of Hodgkin's disease, is supporting a bill in Congress that would authorize $40 billion a year in baseline funding for the National Institutes of Health -- incorporating the stimulus funds into the permanent budget of the NIH.

"We must do this in order to avoid creating a cliff off of which promising research, funded by the stimulus," according to Senator Specter's website, "would otherwise fall, if no additional funds were provided."

The good news is that number of cancer deaths has decreased for the first time in 70 years, according to Dr. Schilsky's testimony, despite a growing and aging population. Survival rates for many of the most common cancers -- including breast, colon, and prostate -- are rising. In fact, there are now 12 million American cancer survivors, up from 3.7 million 30 years ago.

In 1989, my mother was diagnosed with ovarian cancer. She died in 1998 at the age of 63. Since then, researchers have made remarkable discoveries that have shed new light on inherited risk factors. While there still is no cure for this dread disease, which kills an estimated 14,600 women and counts 21,550 new cases every year, I and many other high-risk individuals now have a better chance of living a longer, healthier life.

To die of cancer is one thing. For people living with the disease or caring for family members, it is entirely different.

Susan Sawyers is married to a physician/scientist who receives partial support for his research activities from the NIH.