There is some furor over an exhibit now at Philadelphia's Penn Museum: "The Golden Age of King Midas," showcasing the art of Turkey's ancient Phrygia, a kingdom ruled by Midas in the first millennium BC and known for its superb artistry. Particularly at issue is the curator of the show, C. Brian Rose, suggesting that one of the pieces on display, an ivory statuette known as the "lion tamer" could have been part of the "Midas throne" Herodotos mentions (but never describes) as Midas's gift to Delphi (the Greeks). To date, not even the remains of Midas have been found, although lots of exquisite Phrygian art has been recovered from the so-called "Midas Mound" at Gordion (present day Ankara) and from five tombs to the southwest near the village of Bayindir, with some of the most spectacular objects now on view in Philly through November.

Lion Tamer

Actually, two pieces in the show that I know of -- there may be more revelations to come -- are now being disputed by archaeologists. And getting it right matters because such objects help us to understand human history. The other object, whose image opens and closes the Penn Museum show catalogue, is a silver statuette thought to be of a "eunuch priest." Phrygian priests traditionally emasculated themselves to honor the Phrygian goddess, Matar Kybele.

Silver Priest

The eunuch priest had its public debut in America 27 years ago in a story I wrote with Turkish journalist Özgen Acar for the December 1989 issue of Connoisseur. The magazine (now defunct) at the time was run by Tom Hoving following his other famous run as director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

A little background. . . The art we presented in our above Connoisseur story, experts dated between late 8th century BC and early 7th century BC -- and we interviewed a variety of experts. The pieces were found near present day Bayindir village (ancient Lycia), outside what once were the known borders of Phrygia. But there was a Phrygian presence in the region, including places for travelers and pilgrims to worship Matar Kebele, and Phrygian pottery and metal artifacts had been found in the area prior to the Bayindir discoveries. The Bayindir tombs were also adjacent to a stretch of meadow, considered a resting place for assorted ancient caravans en route to the Mediterranean Sea or making passage over the Taurus Mountains.

As we reported, the Bayindir art was largely considered by experts to be Phrygian in design -- and still is. And because the find was so far to the southwest, the story suggested that the map of ancient Asia Minor might have to be redrawn.

Özgen Acar and I both stand by what we reported then. Özgen has recently emailed me reaffirming:

"I think the Bayindir finds are Phrygian."

I did not have an opportunity to physically examine the Bayindir objects for Connoisseur in the hands-on way I had the Euphronios vases for an Economist magazine story the following year, prior to my coverage of Sotheby's sale of the Bunker and Herbert Hunt collection. Instead, I worked from slides of the artifacts found at Bayindir and from my taped conversations with scholars both here and in Turkey. Frankly, I was astonished by the brilliant artistry upon first seeing the silver pieces showcased in Philly.

Particularly dazzling in design is a belt made of one continuous sheet of metal incised with a four-square repeating pattern that was found in Tumulus D wrapped around the waist of the remains of a 20-25 year old woman (per pelvic bone analysis). The Phrygians loved geometrical design in art, some patterns meant to honor the Phrygian goddess and others intended as puzzles, mazes.

The current row over the two objects mentioned at the top of this story is largely a stylistic one, but, again, one that impacts history. And again, the pieces in question -- both in the Philly show -- are the two statuettes pictured above: (1) an ivory figure known as the "lion tamer" on loan to Penn Museum from the Archaeological Museum, Delphi, Greece, and (2) a silver eunuch priest on loan from the Antalya Museum.

The Penn Museum actually does indicate in its press that the silver priest is from Lycia (Bayindir) even though the object is the star image opening and closing the King Midas Phrygian show catalogue.

Lycia was a culture that was subject to both Near East and Greek influences, and was located in what is now southwest Turkey. It was the home of Sarpedon, the legendary prince depicted both in Homer's Iliad and on the Euphronios krater and wine cup auctioned at Sotheby's for the Hunt brothers (now returned to Italy).

The Penn exhibition also includes pieces found in other ancient cultures that had relationships with Phrygia: Lydia, Urartu, Assyria, Persia, Greece -- perhaps because art historians increasingly take the perspective that art of this period reflects diverse cultural influences as a result of trade, war, marriage and other associations.

But Dietrich von Bothmer, for one, chairman of the Met's department of Greek and Roman art, told me for the Connoisseur article that he clearly thought the silver eunuch priest and other objects found at Bayindir were "purely" Phrygian:

"This is a fabulous discovery. I have never seen anything like it. Each and every piece is of purely Phrygian type."

Oscar White Muscarella, who was early on part of the Gordion excavation team and for decades an Ancient Near East (ANE) expert at the Met, dated the Bayindir tombs at the time of our story late 8th to early 7th century BC -- in concurrence with a 2,000-page computer analysis of fibulae (ancient pins), some of which were found with the remains of the young woman in Tumulus D wearing the silver belt.

Muscarella has more recently told me: "Von Bothmer knew nothing about Phrygian art," saying further that he plans to review the objects presented in the Connoisseur story, claiming pieces may be East Greek. He has already expressed doubts in print about the silver eunuch priest being Phrygian.

We await Oscar Muscarella's further analysis. . .

However, it is the ivory "lion tamer" about which scholars are most divided and the reason is this. The claim has been made by Brian Rose, who also heads the Gordion excavation in Tukey for the University of Pennsylvania, that the piece is Phrygian, late 8th century BC. And in a 2012 article: "The Throne of Midas? Delphi and the Power Politics of Phrygia, Lydia, and Greece," which is based on an unfinished paper by University of Pennsylvania professor and museum curator Keith DeVries, Rose establishes his claim that the lion tamer may be a piece of the Midas throne Herodotos mentioned.

Brian Rose recently emailed me from Gordion, where he is digging for the summer, saying that he stands by the 2012 story:

"Thanks Suzan. I've written about this with Keith DeVries in 2012, and we still stand by that."

Other ANE experts say the link between the Midas throne and the ivory lion tamer seriously lacks evidence and is a distortion of history as well as commercial hype, partly to sell tickets to the Penn Museum show, which has been ongoing since early February.

There was, for example, a black tie "Golden Age of King Midas Gala" six months ago at Penn Museum where (tax deductible) tickets sold for $50,000 (premier sponsor), $25,000 (prime sponsor), $10,000 (sponsor), VIP ($1,500), $500 (individual).

However, the Rose/DeVries perspective is supported by Athanasia Psalti, director of the 10th Ephorate of Prehistoric and Classical Antiquities, Delphi, Greece -- even though a web site that seems to belong to the Archaeological Museum of Delphi indicates that the lion tamer it calls "Master of the Beasts," is from a "workshop in Asia Minor, but is the work of a Greek artisan as indicated by the meander on the base (7th century B.C.)."

A. Psalti recently emailed me saying that she stands by what she wrote when the lion tamer was part of the Met show "Assyria to Iberia," that is, she thinks DeVries/Rose "convincingly" make the case that the piece is from a workshop in Phrygia (also, in said Met show was an ivory statuette probably depicting Kybele, that made its American debut on page 2 of our above Connoisseur article, although neither the Met nor Penn Museum cites our story in its literature):

"Dear Suzan, you may consult the catalog entry of the exhibition Assyria to Iberia, at the Dawn of the Classical Age, edited by Joan Aruz, Sarah B. Graff and Yelena Rakic, New York, 2014, p. 308, nr. 180 with previous references as well as the attached article on the same subject. Should you need any further help, do not hesitate to contact me.

Athanasia"

The Metropolitan Museum of Art catalogue says the following:

"Initially attributed to a Greek artist under strong Near Eastern influence, more recently the figurine has been convincingly suggested to have originated from a Phrygian workshop. It has also been proposed that this unique object was made as a decorative attachment for the magnificent throne of Midas. . . ."

Those experts contesting the Rose/DeVries claim were all once part of the Gordion team: Oscar Muscarella; Ken Sams -- one of three archaeologists who Rose acknowledges as being "responsible in some way for the content" of the current King Midas exhibition and pictured in the Penn Museum show catalog; and Elizabeth Simpson -- a professor at Bard Graduate Center who is director of the Gordion Furniture Project as well as a consultant to Penn Museum.

Muscarella points out in a recent article, "An Ivory Statuette from Delphi---Not from King Midas's Throne," that DeVries's claim that the object was part of the Midas throne was made in January 2002 in articles in the New York Times, Philadelphia Inquirer and Christian Science Monitor (in that chronological order) and in Voice of America, February 2002. DeVries has since died.

Muscarella told me he questions why those news organization would publish the DeVries claim, didn't they do their own assessment of the piece? He's also told me that he contacted the Times about its coverage but got no response.

In his above-mentioned article, Muscarella notes further that the facial features, in particular, of the lion tamer are clearly not Phrygian:

"Although it could be argued that stylistic analysis is in the end largely subjective, even a cursory look at the items compared shows no components of the Delphi figure's face (mouth, eyes, etc.) or hair reflect Phrygian features."

I did spend some time examining the hair on the ivory lion tamer while in Philly because the room was dimly lit. Muscarella is right about the lion tamer's hair not have the interesting texture depicted on other Phrygian art from Gordion and Bayindir.

Ken Sams, who is now a professor of classical archaeology at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, recently emailed me commenting:

"The ivory piece from Delphi, currently on display at the University Museum in Philadelphia, is assuredly not Phrygian [emphasis added], in my opinion, but the product of a west Anatolian or East Greek workshop. The meander is found in Phrygian furniture, but it came to be such a widely used motif that one cannot use it to determine origin. It is a strange piece that I have wondered about for years. The lion, for whatever reason has an erection, for which I know of no parallels."

Muscarella further advised by phone regarding the lion:

"That is not an erection!"

Elizabeth Simpson emailed these salient points to me regarding the lion tamer:

"Have you read Brian Rose's 2012 article in The Archaeology of Phrygian Gordion? His comparanda is not convincing[emphasis added], and it is generally acknowledged by colleagues that there is no evidence [emphasis added] that the ivory Lion Tamer statuette is Phrygian in style per se.The Delphi Museum's posted description [you emailed me] is much more accurate than Rose's contention. Do you know if the Delphi Museum post is official? Is this what the museum label for the Lion Tamer says? Can you please let me know? I am curious.

In terms of the meander design on the base (which is published upside down in Rose's article), this exact pattern is not found on any Phrygian furniture that I know of, and the cross-within-a-square is particularly unusual in that regard.

In terms of form and joinery, the piece was recovered in fragments and has been restored; not all of it is preserved, and I have not seen the bottom of the base. There is a mortise (square cutting) in the back of the figure, but it is shallow, suggesting that the Lion Tamer was not a structural element but decorative. I am not sure how or where the Lion Tamer would have been attached to whatever it once belonged to.

Apart from the style of the ivory figure, the pattern on the base, and its form and joinery, however, one must consider whether the Lion Tamer is from a piece of Phrygian furniture at all -- and whether there is any evidence that it "is" or "may be" from Midas's famous throne.

1. First, a large collection of Phrygian royal furniture survives from the tombs at Gordion, and none of it has carved figures as elements, let alone ivory figures of this sort. You can see what the Gordion furniture looks like from my publications, particularly my 2010 Brill book on the furniture from Tumulus MM (in the MMA library, the Bard Graduate Center library, and elsewhere). A brief summary and bibliography can be found in the Wikipedia article:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gordion_Furniture_and_Wooden_ArtifactsAlthough there are no "thrones" from the Gordion tombs, there was a small chair in Tumulus MM, but it has no carved human figures -- only a crest with small animals in panels carved in relief.

There were ancient Near Eastern thrones that had carved human figures (or deities) as elements, but there is no evidence of this from Phrygia. Such figural elements occur initially in the third millennium B.C., and they are found later in Assyria, Urartu, and elsewhere in the first millennium B.C.

Ivory attachments of various types are well known from the second and first millennia in the ANE [Ancient Near East], but ivory attachments are not found on the royal furniture from the Gordion tombs. Several small, square ivory plaques were excavated in association with wood fragments from Megaron 3 on the City Mound at Gordion, but the figures carved in relief on these plaques are Phrygian in style, like those on the crest rail of the chair from Tumulus MM -- and bear no stylistic resemblance to the Lion Tamer from Delphi. You can read about ANE furniture in my article, "Furniture in Ancient Western Asia," here attached.

Rather, the design and decoration of Phrygian royal furniture involved the abstraction of three-dimensional forms, and elaborate inlaid geometric patterns with complex symmetry, including mazes, apotropaic and religious symbols, and "genealogical patterns." Phrygian furniture seems to be completely different from its eastern counterparts. The examples we have are made of wood, typically boxwood inlaid with juniper and walnut, which survived in relatively good condition in several tombs at Gordion.

So, the ivory Lion Tamer is in no way characteristic of Phrygian furniture, in terms of extant evidence. In fact, it looks completely unrelated in this regard.

2.Second, might the Lion Tamer have come from the throne that Midas dedicated in the sanctuary of Apollo at Delphi? Although I suppose it is remotely possible, there is absolutely no evidence for this contention. As already discussed, there is no evidence that the statuette is actually Phrygian, although it may have been made somewhere in Anatolia. And carved figures of this type are not found on Phrygian royal furniture as we know it.

But let's just imagine that Midas did have a throne with carved figures on it. Maybe he imported it from Urartu or Assyria. Even if that were the case, there is no evidence that this particular carved figure came from it [emphasis in original]. Indeed, the Lion Tamer does not look either Assyrian or Urartian, and it is hard to tell exactly where it was made or what it was once attached to.

I do not doubt that Herodotus saw a throne at Delphi that he believed was dedicated by King Midas [Herodotus 1.14). Unfortunately, he does not describe it.

I gave a lecture on April 2, 2016, at the Penn Museum at the conference, "The World of Phrygian Gordion," in which I said all these things. Brian Rose was in attendance, as the convener of the conference. He heard what I said and appeared to acknowledge the cogency of my argument. Nonetheless he continues to stand by his 2012 article.

Oscar[Muscarella]'s source article on the Lion Tamer is very good on the various issues. I also plan to write an article on "Midas's Throne," as it is important that Rose's article not stand unchallenged."

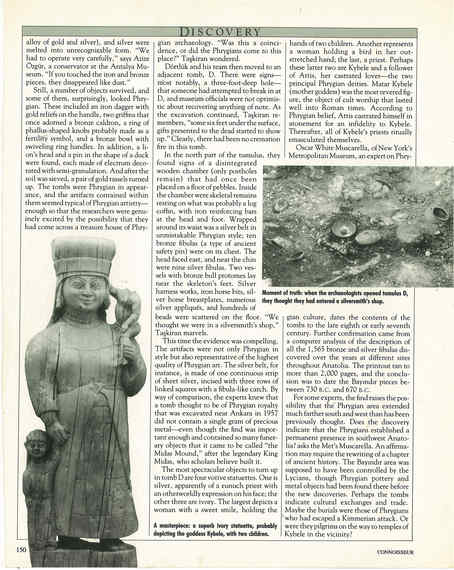

Following is one bronze object found at Bayindir in Tumulus C and now at Antalya Museum that has been suppressed, except for mention on page 2 of our above Connoisseur story, where we describe it as "a ring of phallus-shaped knobs probably made as a fertility symbol":

Phrygian or East Greek?