Like politicians, language sometimes fails to keep pace with the times. Consider the phrase "Taking coals to Newcastle," dating back five centuries to the days when Newcastle, England was coal capital of the world. The adage came to represent the absurdity of bringing something -- in this instance, coal -- to a place where it was already in abundance. The phrase endures, though there are no more such mines in England, and Newcastle, humbled by history, is now a port where foreign coal is off-loaded by the ton.

But in this political season, and particularly in the aftermath of the recent West Virginia Primary, the phrase and its backstory have a special resonance for the presumptive candidates, Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton. For Trump, who imagines he can easily unwind time, bring back the shrinking coal industry, and restore America's preeminence as a manufacturing center, Newcastle may stand as a stubborn reminder that history has no reverse gear. For Clinton, it is a warning that her trademark bluntness - as when she said that the days of the coal industry were numbered - could and probably did cost her dearly. In sum, Trump has a fine ear for telling people what they want to hear, no matter how nonsensical, while Clinton can be politically tone-deaf.

A word of background: A century ago, the UK had 2,600 deep mines producing 207 million tons a year. In December of last year, the last mine closed. Miners wept. A parade featured a black-robed figure of death carrying a scythe. They must have seen it coming. By the mid-1980's, the industry was moribund. Margaret Thatcher, facing striking miners, broke the unions' back. But that confrontation reflected a changing global economy as well, and a realization that the industry was facing perils well beyond politics. In today's global economy, it cannot compete with coal from Russia, Columbia, Australia - and the US.

For Trump, with his constant berating of existing trade deals and his castigation of foreign subsidies and tariffs, the culprit is always identifiable, the solution, obvious: stand firm against other nation's anti-competitive behavior and we will reassume our rightful place as the world's manufacturing center. Whether it is coal, clothing, toys or beef, his simplistic formulas suggest that, freed from foreign impediments or pesky regulations, America will once again realize its manufacturing supremacy and its destiny. Lost jobs will return. American workers will be respected. The middle class will rise again. "We're going to get those miners back to work," he said. " ... the miners of West Virginia and Pennsylvania, ...Ohio and all over are going to start to work again, believe me. They are going to be proud again to be miners."

Such simple prescriptions, pure snake oil, are the basis for Trump's appeal to "Make America Great Again." But that boat has already set sail - literally. Cheaper and cleaner natural gas, concerns over climate change, the lower cost of overseas extraction and labor, the absence of safety and environmental regulations abroad - and history itself - are all arrayed against the miners. So it is with any number of industries. Denying globalism or climate change may be an effective campaign tool to rouse a disaffected base, but is it is also a cruel form of exploitation, patronizing as it is simplistic. It is also grossly irresponsible, raising false hopes and removing incentives to plan for a changed future. No one knows this better than Donald Trump, the businessman, who routinely exploits cheap foreign labor for personal gain.

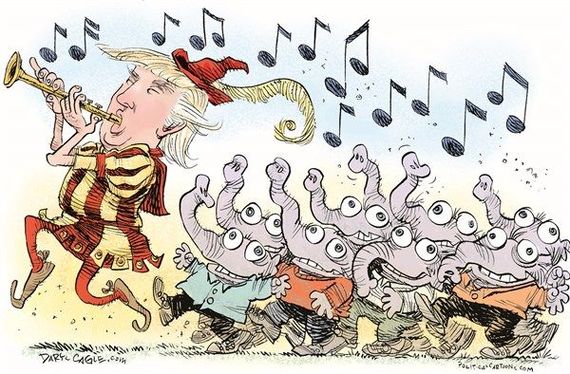

Trump is either schizophrenic or cynical in the extreme. His appeals to defy globalism and his suggestion that its casualties are solely the result of dim-witted and out-maneuvered bureaucrats, plays well in a country reeling from economic upheaval and eager to find a scapegoat. But it does not address the underlying realities. No one in Newcastle today suggests that the coal industry could be resuscitated with tougher trade talks. Last year, not coincidentally, renewable energy, for the first time, provided more electricity to the UK than coal. But a prideful Trump is a modern day King Canute, who imagines that he can command the tides to retreat. Besides, if he is wrong, he can always just walk away from the wreckage, as he has made a habit of doing with serial bankruptcies, divorces, and lost business wagers.

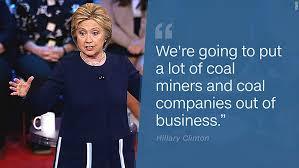

For Hillary, the lesson of "Coals to Newcastle" is different. In March, she told an audience in Ohio that "we are going to put a lot of coal miners and coal companies out of business." She attempted to walk back that apocalyptic warning, and to contextualize it, but her words demonstrated an utter lack of sensitivity, remarkable for America's former diplomat-in-chief. It also cast light on a personality flaw that, at times, borders on the political equivalent of Asperger's - a failure to read the most basic social cues.

It was not merely a gaffe but a revelation of how little she understands the impact of her words and deeds. Consider the optics of her private email server while at the State Department or her obscene speaking fees from Goldman Sachs. Or her statement in 2014 that she and Bill were "dead broke" when leaving the White House, struggling to pay the mortgages on their homes - plural (a $1.7 million New York house, a $2.85 million seven-bedroom manse in Washington, D.C.) In each case, she appeared mystified by the resultant uproar, blinded by privilege and a sense of her own virtue.

A few months in northeastern England, as in West Virginia, would show her that coal is more than the black bituminous and anthracite scraped from deep inside the earth. I have spent months in both England's County Durham and in Logan County, West Virginia, epicenters of coal country. In Logan County, I went a mile inside a mountain, lying on my back as I hurdled on a tiny sled through the dark of a low-seam coal mine. Hours after exiting I discovered the coal had penetrated my clothing, and filled my nostrils. But over generations, coal also seeps deep into the pores of a culture.

In advertently declaring war on the miners themselves, Clinton threatened to take away not only their livelihoods, but also the character and identity of entire communities. There, King Coal is inextricably linked to notions of self-worth, manliness, and independence, not to mention the music, dance, stories and faith of the region. To understand how deeply Clinton's threat struck, one might visit Beamish, an open air museum depicting English life in the 19th and early 20th Century, in the Vale of Durham ten miles south of Newcastle. One of the most popular sites is the Mahogany Drift Mine that closed in 1958 but which is a featured attraction. There, former miners guide countless visitors - hundreds of thousands annually -- through its twisting tunnels. It is where the children and grandchildren meet their heritage. For many, it is more pilgrimage than museum.

And each July, twenty miles south of Newcastle in Durham city, some 150,000 people gather to observe the Miners' Gala, an outpouring celebrating the culture of coal that is no more.

But for many former miners, the future remains bleak. Some are in "council housing" - public housing -- some have been forced to take menial jobs, others have been unable to find work at all. Decades later, stripped of work and identity, some are like walking ghosts, their guildhalls vacant, their statues of pitmen adorning parks and town squares. (One such statue shows a miner, his chest ruptured where his heart has been torn out.)

Clinton's words conjured up just such a vision for America's miners. The inevitability of their fate has already begun to unfold. Twenty-five years ago, one in 14 jobs in West Virginia were in coal mining. Today it's one in twenty-eight. But to be told, almost gleefully, that the remaining workers also face extinction -- casualties of clean energy policies - reflects as much on the callousness of the candidate as on the dire future that awaits.

The cruelty of Trump's glib promises that he can single-handedly "Make America Great Again," ignore economic realities. The certitude of Clinton's manner gives short shrift to human casualties. "Coals to Newcastle" once represented an assumption that history was predictable, prosperity secure. It implicitly derided those irrational enough to challenge such economic hegemony. Now the phrase is but a verbal artifact, a token of discredited wisdom, and a measure of just how swift and complete the reversal of fortune can be.

Still, it might profit the candidates to consider the phrase and draw what lessons they see fit. Trump, a cartoonish figure, has drawn a cartoonish world of hapless and perfidious politicians at home, and villainous leaders abroad. It is not imagination, but fantasy that he peddles as he panders to those most vulnerable and resentful. A Pied Piper of impossible promises, he offers to lead them to a place that does not exist - the past. For her part, Clinton, scarcely less prideful than her opponent, offers a sometimes-brutish form of determinism that threatens to crush as it elevates. Words matter. Perceptions matter. It is not the "vast right-wing conspiracy" that now threatens to ensnare her, but her own sense of rectitude, and her peculiar brand of noblesse oblige, gilded with entitlement. But offering advice to politicians is, well, like taking coals to Newcastle.