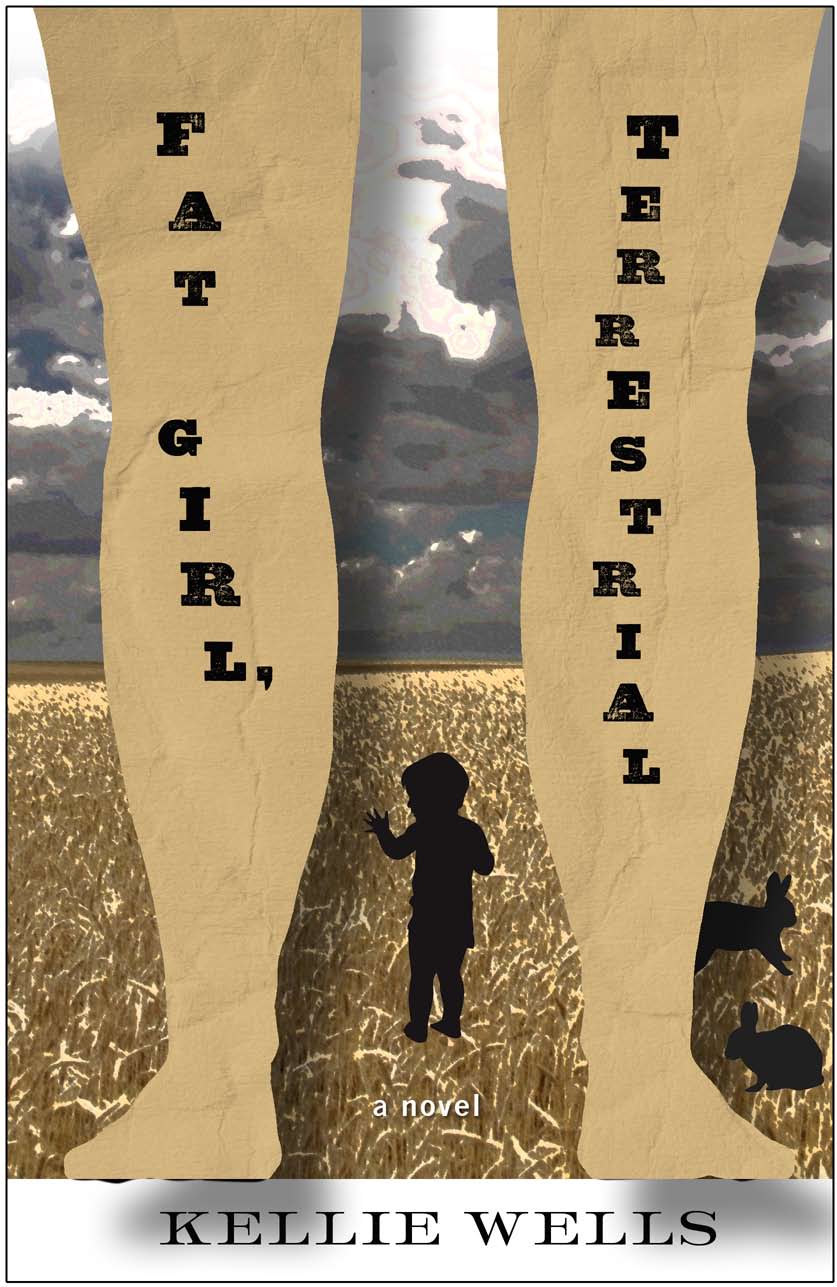

Kellie Wells is the author of three acclaimed works of fiction, including Compression Scars, the winner of the Flannery O'Connor Award. Her latest, Fat Girl, Terrestrial (Fiction Collective Two), tells the story of Wallis Armstrong, a giantess in the town of Kingdom Come, Kansas, where children mysteriously vanish. The novel has picked up endorsements from Kathryn Davis, Kate Bernheimer and Jaimy Gordon, who raves that "When the present generation of writers shakes down to its unique and irreplaceable voices, Kellie Wells will be one of them." I spoke with the University of Alabama professor about her inspiration for the wild storyline, her attention to language and why the suffering of the body makes for good fiction.

Your narrator, Wallis Armstrong, is a giantess and a miniaturizer of crime scenes -- where did this material come from?

I stumbled upon the idea of the crime scene miniatures when I saw photographs of the Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death, which are crime scene dioramas built by a woman named Frances Glessner Lee. She founded the Department of Legal Medicine at Harvard in 1931, and she produced these extraordinary doll houses, and did so with the most fastidious care, in order to train detectives in the art of sniffing out the devil in the details. These doll houses of death seem to me inherently paradoxical, and to be the very shape of that which they depict, because in these dioramas villainy meets innocence: A doll in a tutu lies twisted and bleeding on a living room floor, another dangles from a noose tied to the rafter of a barn, Barbie and Ken are all grown up and plunged into the skulking nefariousness alurk in the world. There's a nicely arresting contradiction in a child's toy being used as a tool of murder investigation, a plaything used to recreate homicidal violence, and this seemed to me somehow a fitting contradiction and avocation for a giant woman made ill at ease by her amplitude.

Jaimy Gordon says of you that you're "a prose stylist...whose intellect and language bid one another beautifully to a dance." How is the novel's style suited to its subject matter, its themes and compulsions?

Wallis's voice is, like her body, capacious and, well, inclusive. It's a sort of protean mash-up of various idioms, in various registers, from the rural demotic to the decidedly mandarin to the noir patois of a hard-boiled crime novel. Wallis's younger brother, Obie, believes the only explanation for his sister's size is that she is the incarnation of God on Earth, and she longs to live up to his adoring estimation of her, to be worthy of his devotion. The narrative voice is her expression of this longing.

You're interested in the figure of the female grotesque. Why is the failing, ailing, extreme, or fantastically distorted body a recurring fascination for you?

Stanley Elkin says, "the Book of Job is the only book," the only story worth telling. I too think (serial) suffering, in one form or another, is at the heart of every compelling story. The body, however stoic, often wears its dilemma on its sleeve, so the fantastically distorted body and the resulting alienation are a kind of concrete, objectified, encapsulated theater of the dramatic abstractions of everyday life: treachery, disloyalty, deception, infidelity, failure, disappointment, i.e. suffering. The mortal body is necessarily eventually estranged from itself, from its occupant. Outsiderhood begins at home.

Do you think of yourself as a comic writer?

I'd like to. In the work of the writers I admire and return to, the drama and pathos are made all the more harrowing by the comic. I do like it when the yuks are consequential; I like it when the darkness is leavened only to be returned to a deepened darkness. I think my sensibility naturally veers in that direction.

You're a writer who also teaches. Do these feed one another? Interfere with one another?

For me, writing and teaching are symbiotic activities, and they have to be or else one would eventually seek to blacken the eye of the other. One thing teaching forces me to do is articulate precisely what my own aesthetic and intellectual interests and positions are and to confront and reevaluate them over and over again. So, with the help and wisdom of my students, I get to plumb a lot of ideas, work through a lot of issues of craft, before I sit down at my desk, and I hope being constantly and actively and daily engaged in this sort of literary conversation keeps me imaginatively nimble and evolving, ossification being one of my fears (back to the body in decline, whomp)!