In 1999, Vermont had 1,782 dairy farms and 160,000 cows. Now the state has fewer than 1,100 farms and only about 135,000 cows. For the past year, Northeast dairy farmers selling to the commodity market have lost money every day. It's not just that there's a worldwide glut of milk, keeping prices down, but feed, fuel, and other costs are up. The fear is that another large wave of dairy farmers is about to quit. In Vermont and wherever dairy farms are important, the landscape is under threat.

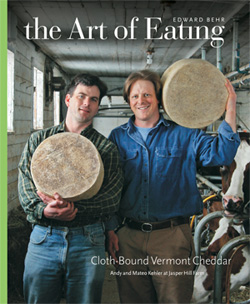

In 2005 at Jasper Hill Farm in Greensboro, Vermont, in the rural Northeast Kingdom, brothers Andy and Mateo Kehler were turning milk from their 40 cows into several flavorful, lucrative cheeses, including their well-known Bayley Hazen Blue. They understood that farms are integral to the region's character. Their own small farm was already putting $300,000 a year into the local economy. The dairy farmers around them were selling fluid milk on the commodity market, and then as now many were going out of business. Although some other kinds of farms, mostly very small, were starting up, the Kehlers were concerned about the future of New England agriculture.

Their solution, the Cellars at Jasper Hill, a $3 million project that opened in 2008, was an outgrowth of their cheesemaking. The Kehlers knew just how hard it is to be a farm cheesemaker. You farm, you milk, you make cheese, you age it, you find a market, you handle all the details of sale and distribution. Not many people have the talent or skill to succeed at all those diverse tasks. Not many have the capital to hang onto cheeses while they age. The Kehlers knew that the big leap in value occurs when milk becomes cheese. They figured they could help farm cheesemakers by buying their new cheeses (paying half up front) and handling the aging, marketing, and distribution. They wanted to lower the barriers to entry for farm cheesemakers.

The seven Jasper Hill cellars are underground, radiating in a half circle. After three years of operation, the 22,000 square feet are 30 percent full, which is ahead of schedule. The Kehlers had a piece of unusually good luck from the start. Nearby Cabot Creamery, part of the 1,200-farm Northeast dairy co-op Agri-Mark, had been thinking of a cloth-bound cheddar but didn't want to undertake the aging. That gave the Cellars a reliable large volume of cheese, now just under half its total. In the first year of operation, the Cellars shipped 70,000 pounds of cheese; last year, even with the poor economy, the figure was 250,000 pounds; and this year the Kehlers expect around 400,000 pounds. Mateo says, "We're picking consumers off the commodity bandwagon." Besides Cabot Cloth-Bound, the Cellars hold Grafton cloth-bound cheddar and cheeses from Jasper Hill and other regional farms: Cobb Hill, Crawford (Vermont Ayr), Landaff, Ploughgate, Scholten, Twig, and von Trapp.

At Jasper Hill, the natural rinds breathe. The cloth-bound surface of the cheddar becomes mottled with essential white, gray, and beige molds. The cellar air is cool, but warm and humid enough for a lively growth of yeasts and other micro-organisms. Flavor diffuses from the surface through the cheese, and a loss of moisture concentrates the flavor. An enormous amount of hand labor is required, especially turning and brushing for optimal ripening. Each wheel of cheddar is handled at least 70 times before it heads to market. The wheels sit on thousands of spruce planks, which between batches must be washed, a process that is only partly mechanized.

Older isn't automatically better. Age makes a poor cheese worse. And the cult of very old cheddar is somewhat silly. A properly aged, natural-rind cheddar reaches its peak of flavor at ten to 14 months. The only way a cheese can survive years of aging is to be sealed in plastic and refrigerated.

Every cheese varies from batch to batch, but consistent high quality requires specific knowledge and precise skills. The Kehlers had expected to find 20 small farms producing high-quality cheese for the Cellars, but they have only seven. "What's missing," Mateo says, "is the technical support to create that body of cheesemakers."

When it became clear that lots of farm cheeses wouldn't quickly appear, the brothers began to think of ways to bring them into being. A proposed new facility of the Vermont Food Venture Center, funded by federal grants and situated in the nearby town of Hardwick, will be an incubator for food products. There Jasper Hill will turn milk purchased from small dairy farms into cheese, with the hope that some of the farmers will in time start their own cheesemaking, drawing on skills learned at the center. If that works, it could serve as a model for other groups of farms, other local cheese plants, and other regional aging cellars, like the system used in the Jura Mountains of France to produce the great cheese Comté.

Some kinds of farming don't take much land, and if Vermont and many states are keep a significant amount of farmland, a large portion of it will have to be in dairy. Still, it takes a lot of cheese to affect the landscape. The superior milk for all the Cabot Cloth-Bound, for control and consistency, comes from just one farm. Kempton Farms in Peacham milks 300 cows, and each month the Cloth-Bound takes just four days' worth. The Cabot plant, using milk from many farms, receiving commodity prices, makes a total of 18 million pounds of non-cloth-bound cheddar a year. But the number of small farms making cheese could add up.

That would require a lot more projects like the Cellars at Jasper Hill. Some day Vermont might support five such projects with 20 farms each, which would be an important step out of the commodity market. The process, however, would take years. "I believe we have the power to make an impact and demonstrate that there is an alternative to the commodification of our food, our landscape, and our communities," Mateo Kehler says. "We're taking the long view."

-- Ed Behr, Art of Eating

Follow HuffPost Food on Twitter and Facebook!

Follow HuffPost Food on Twitter and Facebook!