By Pei-Hua Yu

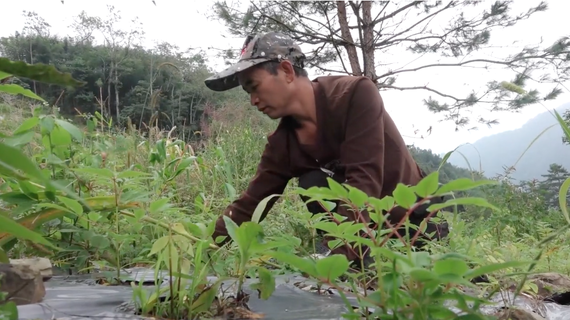

HSINCHU, Taiwan -- On his scraggly field in the village of Cinsbu, 1,700 meters above sea level, Ino Yumin loosens the soil with a hoe and pulls up the weeds around his crops with a sickle. Unlike the nearby commercial field producing thousands of a single strain of organic cabbage, Ino's small field grows 30 varieties of indigenous millet, four types of corn and one traditional herb used locally.

Ino started to collect varieties of crops around 20 years ago as he foresaw the problems of planting only select, imported crops, with the climate getting warmer and more unpredictable.

"We had snow every winter around 30 to 40 years ago," he said. But the snowy days have been decreasing year by year. "Over the past decade, we started to find some plants from lower elevations here," he continued.

The farmer's diverse field highlights one of the ongoing efforts of the Atayal people to adapt their ancestral heritage to the changing climate. Having lived in the Taiwanese mountains for thousands of years, the ethnic Atayal kept the indigenous varieties of crops and flexible strategies to interact with nature. Long before international scientists and Taiwanese officials began paying attention to the pressing problem of climate change, the Atayal have seen and lived the changes firsthand.

Ino, 52, is a member of Taiwan's Atayal ethnic group, one of the 16 indigenous groups of Taiwan that has been dispersed the most in the mountainous areas. Collectively, they account for two percent of Taiwan's current population.

Over the last 120 years, the average temperature of Taiwan has increased 1.2 degrees Celsius, higher than the world's average of 0.7 degrees, according to Taiwan's Central Weather Bureau. This increase has accelerated over the last 30 years. And in that time, yearly rainfall patterns have fluctuated -- the number of rainy days has dropped, but the number of days with heavy rain has increased.

The rising temperature is a direct result of global warming. However, whether it has contributed to the rise of extreme rainfall, especially typhoons, is for now undetermined, said, Hsu Huang-Hsiung, deputy director and a research fellow of the Research Center for Environmental Changes, Academia Sinica in Taipei.

Without a written calendar system, the Atayal determine their agricultural routine by observing the floral life cycles. As the Sakura cherry blossom blooms, for instance, they sow the millet. "However, over the past ten to 20 years, the Sakura blossoms earlier and earlier. We felt confused by the climate patterns," said Yuraw Icyang an Atayal elder.

Since the 1970s, many of Cinsbu's farmers have given up most of their traditional crops. Instead, they have planted the imported, improved strains of temperate fruit trees like apple, pear and peach trees. Initially these brought in good income, the farmers say. However, as the climate has warmed, the fruits have become less sweet and more watery. They also attract more bugs, forcing the farmers to rely more heavily on chemicals to keep the appearance of the products intact.

In his barn, Ino keeps tassels of seeds from over 30 millet varieties collected from indigenous villages in Taiwan.

He recalls how he acquired his botanic knowledge as a child from his father and uncle in the mountains. Ino now distributes seeds to other farmers free of charge as long as they sow every year. All the neighboring villages grow millet varieties he shared from his breeding field.

"I thought it was time for us, the indigenous people, to take up the knowledge passed down by the elderly," he said. "I am breeding to prepare for the foreseeable 'food crises' in the coming 20 to 30 years."

On a flat field belonging to Cinsbu farmer Ataw Yupas, four indigenous varieties of sweet potatoes grow in neat rows. Three years ago, he grew an improved variety and stored its sweet potatoes with the indigenous ones in a wood-walled pit over the winter. The Atayal traditionally stockpiled sweet potatoes to sustain their food provisions for the coming year.

When Ataw opened the pit three months later, all the sweet potatoes of the improved variety had decayed, while the indigenous ones remained intact. "We realized that we had to preserve the local varieties passed down from our ancestors, who had been here for hundreds of years," he said. This month, he will teach the local elementary school students to build a pit for sweet potatoes, another way of passing ancestral knowledge on to young people.

Taiwan, as one of the areas most vulnerable to climate change on the globe, has recently passed the Greenhouse Gas Reduction and Management Act in June, and the Intended Nationally Determined Contributions to reduce its 2030 carbon emissions by 50 percent. It has been unable to join many United Nations conferences, as it isn't a UN member for political reasons.

"It's a pity," said Peng Chi-Ming, executive director of WeatherRisk Explore Inc., Taiwan's only licensed weather forecasting company. "Taiwanese people have lots of experience to educate and help other people."

This story is part of a reporting partnership between The GroundTruth Project and The University of Hong Kong's Journalism and Media Studies Centre.