By Sara Lipton, Cullman Fellow, The New York Public Library

There's a scene toward the end of Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade that I have long been stuck on.

After a long and dangerous quest Indiana -- together with his father, a professor of medieval literature, and a German scholar of unspecified field -- have finally located a hidden chamber dating back to the First Crusade. In the chamber are dozens of chalices, one of which is the Holy Grail, all guarded by a 900-year-old knight. And what do these learned scholars do when confronted by this living relic of the distant past? Brushing quickly past the knight, they head straight for the cups!

At this point I find myself yelling at the screen: "Talk to him! Ask him questions!" After all, how many times do medieval scholars get to do oral history? Why must this long religious and historical quest end not with knowledge, but with a thing?

But of course the filmmakers know their audience far better than I. An object that was once (allegedly) touched by Jesus has inherently greater interest than any man, even a 900-year-old crusading knight.

But of course the filmmakers know their audience far better than I. An object that was once (allegedly) touched by Jesus has inherently greater interest than any man, even a 900-year-old crusading knight.

Moreover, that object must needs be beautiful. Even though the moral of the story is anti-materialist -- the evil treasure-hunting tycoon dies because he fails to remember that Jesus came as a humble carpenter's son -- the camera lingers lovingly on the gleaming gold of the false Grails. And even though the True Grail is shown as a simple, unadorned glass, the director cannot resist having its interior glow with a golden light. All that is godly, it seems, must glitter.

Far from being a conceit of Hollywood, this need to beautify the sacred is one of most universal of religious impulses. As the New York Public Library exhibition Three Faiths: Judaism, Christianity, Islam (opening October 22, 2010) amply demonstrates, it is shared by the three great monotheistic faiths of western civilization.

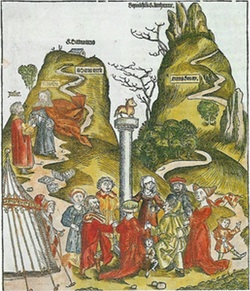

Of course, all three faiths are first and foremost religions of words and ideas. They share the same conception of a single, immaterial, unseeable deity, and they all agree that God's message was revealed not in images or objects but in sacred texts. But for most human beings it is difficult indeed to feel devotion for a disembodied abstraction. The need for visible signs, even of ineffable truth, is recognized throughout the history of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Even as Moses was receiving Revelation from God himself, the Book of Exodus (Chapter 32) and the Qur'an (Surah 20) both tell us, his people begged for a statue to worship. And although Moses destroyed the Tablets of the Law in rage at this infidelity and ground the Golden Calf to dust, he also at God's command housed the Tablets in a Golden Ark adorned with images of cherubim (Exodus 25 and Qur'an 2:248). Words and ideas are paramount, but we grasp them through things.

And although Moses destroyed the Tablets of the Law in rage at this infidelity and ground the Golden Calf to dust, he also at God's command housed the Tablets in a Golden Ark adorned with images of cherubim (Exodus 25 and Qur'an 2:248). Words and ideas are paramount, but we grasp them through things.

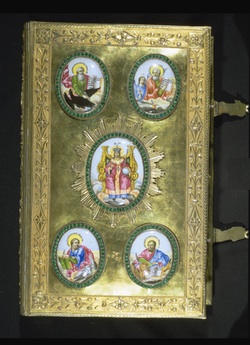

Above all, Jews, Christians, and Muslims have expressed their love for God by enshrining his words in beautiful books. Many of them obviously agreed with Spielberg's evil tycoon -- the precious metals and gems lavished by Catherine the Great on the binding of the Russian Altar Gospels displayed in the Three Faiths exhibition out-dazzles any prop designed by Hollywood.

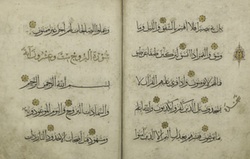

But beauty in a book is by no means limited to dazzle and shine. The creativity, variety, and - sometimes - controversy (though this theme is very much downplayed in favor of commonalities) of scriptural adornment are evident everywhere in the exhibition. Sometime the very letters become decorative designs (see the elaborately ornate and well-nigh illegible initials in the Harkness Gospels from tenth-century Brittany, or the large word panels in the thirteenth-century German Hebrew Xanten Bible, or the stunning calligraphy of the fourteenth-century Turkish Qur'an).

Sometimes the texts are almost swallowed up by the luscious illustration surrounding them, as in the early sixteenth-century Christian Book of Hours (Roman Use), or the sixteenth-century Persian Legends of the Prophets, or the stunningly ornate eighteenth-century Italian ketubah (marriage contract), obviously meant to be framed and displayed rather than read and referred to.

Sometimes the meaning of holy words seems outright irrelevant - the gold, paper, and clay amulets and incantation bowls made by Jews, Christians, and Muslims alike seek power in the characters' shape or sound rather than their sense. Many makers of luxurious books apparently wanted to have their cake and eat it too: the face of the prophet Muhammad is left blank in an illustrated Life of the Prophet to avoid any possibility of idolatry. And while early modern Jews, Muslims, and Protestant reformers might well have shuddered at the depiction of the Trinity in the Brigittine Prayer Book, Catholic teachers (in commentary texts such as those displayed here) insisted that such pictures helped stimulate faith, so long as they were not mistaken for God himself.

For such men, as for all the people who made the beautiful books, scrolls, and objects displayed here, a religious or historical quest must of course end with knowledge... but it can begin with a thing.

Sara Lipton teaches medieval history at the State University of New York, Stony Brook. She is the author of Images of Intolerance: The Representation of Jews and Judaism in the Bible Moralisée. Lipton is currently the 2010-2011 Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Fellow at The New York Public Library's Dorothy and Lewis B. Cullman Center for Scholars & Writers, where she is working on a book called Dark Mirror: Jews, Vision and Witness, 1000 - 1500, which seeks to bring coherence to the dizzying proliferation of medieval Christian images of Jews.Images:

Late twelfth-century chalice in Reims Cathedral TreasuryIsraelites Worship the Golden Calf, from the Weltchronik, 1493

Altar Gospels, Gilt Binding from the Reign of Catherine the Great, Evangelie naprestol'noe (Altar or Elevation Gospels, in Church Slavic), Moscow, 1791, Rare Book Division, The New York Public Library.

The Qur'an, Qur'an, Probably Turkey, AH 734 (1333 CE), Spencer Collection, The New York Public Library.