By Jerry Mitchell  After the terrorist attack on 9-11 and the nation's response, anger and grief overwhelmed artist Robert Shetterly.

After the terrorist attack on 9-11 and the nation's response, anger and grief overwhelmed artist Robert Shetterly.

"It finally occurred to me that if I stopped obsessing about (then-Vice President) Dick Cheney and began surrounding myself with Americans I admired, I'd feel better," he said. "I painted Walt Whitman, our essential democrat, then Frederick Douglass and Sojourner Truth."

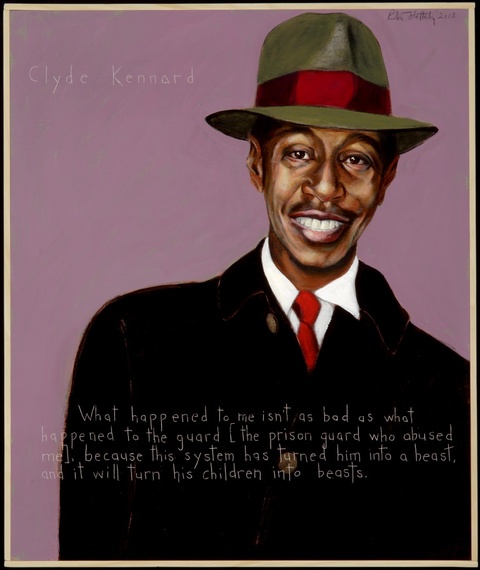

His latest portrait is of an American he never knew before--Clyde Kennard, whose portrait was unveiled Thursday night in the nation's capital at an event sponsored by Teaching for Change and Americans Who Tell the Truth.

"It is one of my goals to find stories like Clyde's and resurrect them -- not simply to honor them, but to inspire others, to fill in lost history," Shetterly said. "Many people know about some of the people who integrated schools in the South in the 1950s and '60s. What they don't know is who tried first and failed, was blocked, was martyred."

He said he hopes Kennard's story will inspire children, "a story that gives us permission to act, to be courageous."

After serving in the Army in the Korean War, Kennard attended the University of Chicago, working toward a degree in political science.

His stepfather died, and he returned to Mississippi to help his mother run their farm outside Hattiesburg, Miss.

Desiring to finish his degree, he repeatedly tried to enroll at the all-white Mississippi Southern College (now the University of Southern Mississippi). When he showed up on campus to enroll in 1959, two constables arrested him on charges of illegal possession of alcohol. (Mississippi Sovereignty Commission records show the alcohol was planted in his car.)

Despite being fined $600 on the bogus charge, Kennard remained dedicated to attending Southern and talked of taking his case to federal court.

On Sept. 25, 1960, a constable arrested Kennard, claiming he masterminded the theft of $25 in chicken feed.

A judge sentenced Kennard to the maximum seven years in prison. The admitted thief? He walked free and continued to work at the same job.

At the state prison in Parchman, Kennard picked cotton on the sunup to sundown gang, and one guard especially abused him. He became ill, but medical treatment came slowly. By the time doctors had diagnosed him, he was dying of cancer.

At the request of Medgar Evers and others, then-Gov. Ross Barnett released Kennard in January 1963, and Kennard expressed no bitterness, declaring, "I love Mississippi."

In his last days, shriveling from cancer in a Chicago hospital, he declared, "What happened to me isn't as bad as what happened to the guard [that abused him], because this system has turned him into a beast, and it will turn his children into beasts."

Kennard died on July 4, 1963--the anniversary of the document that had promised "all men are created equal."

In 2005, the man charged with stealing chicken feed told The Clarion-Ledger that Kennard had actually done nothing wrong.

History teacher Barry Bradford and his students teamed up with Steve Drizin, the Director of the Center on Wrongful Convictions at Northwestern University's School of Law, LaKeisha Bryant, the president of the Afro-American Student Association at the University of Southern Mississippi, and civil rights activists Joyce Ladner and Raylawni Branch, and pushed for Kennard's exoneration.

On May 16, 2006, Circuit Judge Bob Helfrich threw out Kennard's conviction.

"It is a right-wrong issue," he said. "To correct that wrong I'm compelled to do the right thing and declare Mr. Kennard innocent."

"It is a right-wrong issue," he said. "To correct that wrong I'm compelled to do the right thing and declare Mr. Kennard innocent."

Kennard's life moved Shetterly.

"How he refused bitterness, how deep his courage ran, one cannot but marvel at him," the artist said. "Knowing a story like that of Clyde Kennard allows each of us to be a better person.

"There is no better teacher than courage. Clyde Kennard is a great teacher."

![]()

Jerry Mitchell is an investigative reporter for The Clarion-Ledger in Jackson, Miss. His work has helped put four Klansmen behind bars, including the assassin of NAACP leader Medgar Evers in 1963 and the man who orchestrated the Klan's 1964 killings of three civil rights workers. Mitchell, a 2009 MacArthur fellow, is writing a book on cold cases from the civil rights era.

Images

Top: Americans Who Tell the Truth portrait of Clyde Kennard by Robert Shetterly. Learn more.

Bottom: Dorie Ladner, Dick Gregory, and Joyce Ladner at the Clyde Kennard portrait unveiling on November 14, 2013. By Rick Reinhard. More images.