If you ask a Seattleite what is the local signature food, they will say two things: wild salmon and Dungeness crab. Indeed, these are known worldwide as the native food of the Pacific Northwest.

Most local are aware of the wild salmon's life. Out-of-towners not so much. If you want to know more, just visit the Ballard Locks and take the tour offered.

Salmon start their life in freshwater. This is where it spends the first years of its life. Walk around at the locks and you will find out about the salt and fresh water and the fish ladder. Grown up salmon have to return to freshwater where there were born when they reach adulthood and is time to spawn. The locks provide the infrastructure for salmon to move step by step. "Their bodies have to adjust to fresh water as it may be hard on them", says our tour guide at the Ballard Locks. When the tide is in, it is easy but when the tide is out they have more steps climb. That's why there is a long fish ladder with many steps."

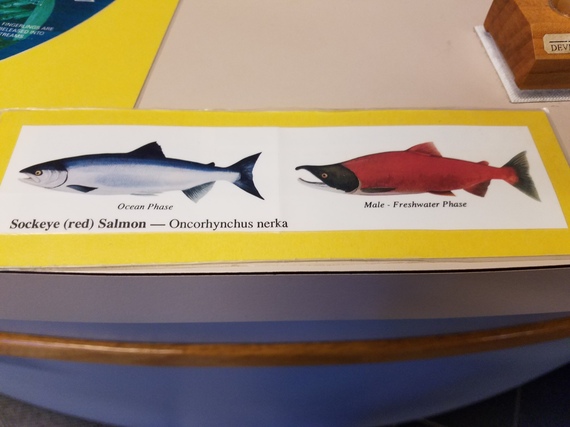

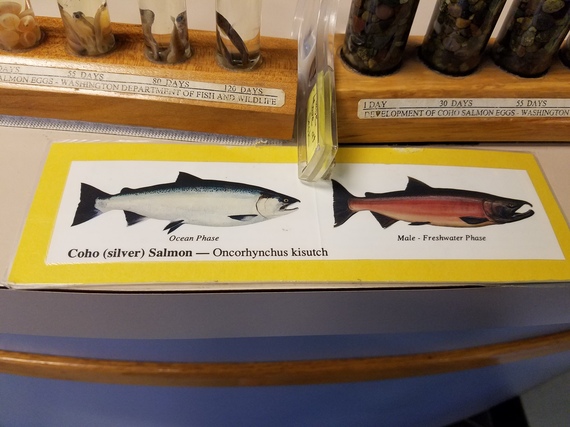

Salmon travel and come to the ladder because they recognize the smell and the taste of the waters where they were hatched. The locks provide the only way to come out to the ocean from any of the creeks or rivers from Lake Washington. So following their instincts, they remember the smell and they come back to the ladder, the only way back into the lake. At this point, they have stopped eating and their body goes major changes as well. They start to change color, they get redder and redder and male salmon develop what is called kype, when the lower jaw extends wide out and curves up and the upper jaw extends down. So now they have sharper teeth to push around the river and to fight over females.

When they arrive at the fish ladder, they rest. When they are to leave, they escape through the last three steps up into the canal. They swim eight miles to Lake Washington and that can take a while.

Those that return to the hatchery, swim north to the Squamish river at Issaquah. There, they are removed from the river and the hatchery employees remove the eggs from the females and milk the males to get their milt (sperm) to fertilize the eggs. Then they put the eggs in tanks, feed the little fish until they are much bigger, they clip the fin on top and send them back to the river to grow up. Their life has started at the hatchery but then it continues to the streams and lakes and finally to the ocean. When they spawn, the female searches for a spot in the river to lay her eggs. As she approaches the water she came from, she has to find the perfect size gravel: not too small because the eggs will be smothered or too big because she will have a hard time to pick them around with her tail. By using her tail on her side, she pushes the gravel out of the way. So she has a nest big enough for two. The male is next to her, and may even do the courtship dance over the nest. Finally she drops her eggs, nearly 800 eggs and the male squirts enough milk to fertilize them. Afterwards she again swims upstream, kicks the gravel with her tail and the river brings it down and covers her eggs up and kicks and cleans all the dirt all the way away; now she has a new nest. She moves to a different nest for up to five times on the whole.

By that time, the salmon are mortally exhausted, with all the digging and fighting and lack of food for months. Even then some males still want to spawn. Eventually, their short, hard and tragic life will end when they finally die in the river where they were hatched. But as conscious parents, they ensure that the young offspring have a healthier place to grow up. It is their dead bodies that feed everything in the river including their offspring. The nutrients from their rotting bodies feed the eggs, and when they hatched out, they provide the food that the local ecosystem needs for a teaming population of insects and small aquatic animals that the baby salmon need to eat. This circle of life is called semelparity.

The dead salmon also are food for other animals and plants in the streams and adjacent forests such as trees and bears. In all, over 120 species rely on salmon.

Out of the 5,000 eggs that end up in the gravel all covered up and fertilized, only 500 will emerge as a young fresh water fish called a "smolt". Each species of salmon spends different periods of time as smolts. Coho for example spends a year and a half in this juvenile state. By the time they are grown enough to start heading down to the ocean and salt water, only fifty will have survived. On their way to the ocean, through the lake, through the ship canal, and voyage through Puget Sound and the Salish Sea, only thirty will survive bigger fish, birds, harbor seals, sea lions, orca whales and finally humans.

Those left will head out a hundred miles off the coast where they will eat and grow more and follow various migration patterns. When the three-year old Coho returns home, only five will have survived and then they have to go back through the same gauntlet of predators as they return through Puget Sound. As they enter Puget Sound, they get closer and closer to where their home stream is by smelling the water. When they arrive at the locks, only five have returned. Of these, only two will successfully spawn. Some will not find a spot in the gravel, or they won't win the battles over the females, others take a wrong turn and get lost.

Being the biggest strongest male is not always the key to breeding. Sometimes, a smaller male salmon will slip past a larger spawning male and drop a little milk on the fresh unfertilized eggs before the bigger male can get there. Although for humans this may be considered adultery, is actually a good thing for the species because they are passing their genetics on and increasing the gene pool. Therefore, if something happens which threatens the species such as a disease or changing climate, the increased genetic diversity ensures that some will survive and carry on the species.

So the ones who return to the locks are the survivors? Yes, indeed. Less than one in thousand comes back to the locks, less than 1% off the eggs survive adulthood. So the Chinook, Coho, and the Sockeye are four years old when they come back to the locks after a long and amazing voyage.

Next time you have a piece of wild salmon on your plate, think for a moment about this rather short but insightful life of this amazing creature.

More info

80% of the Coho are going to the hatchery and is the same for Chinook. For Sockeye it is the reverse with only 20% being from a hatchery.

You can recognize a hatchery salmon from a missing fin. They are clipped off at the hatchery before they are released in order to identify the wild ones from those of hatchery origin. If you are out in the ocean and you catch a wild salmon when they are not permitted to be caught, you have to put it back. Chinook is an endangered species so you can't keep it if not allowed to. The wild Chinook in the Puget Sound is struggling so we all need to do our part to replenish its populations.