The George Eastman House in Rochester, New York announced last week that they have unsealed the journals of actress Louise Brooks. The actress kept journals from 1956 until her death in 1985. According to an Eastman House archivist, there are 29 journals with approximately 2000 pages of hand-written text. She bequeathed them to the photography and film museum with instructions they remain sealed for 25 years.

The announcement has everyone wondering what they will reveal, and what sort of literary talent was this now iconic silent film star.

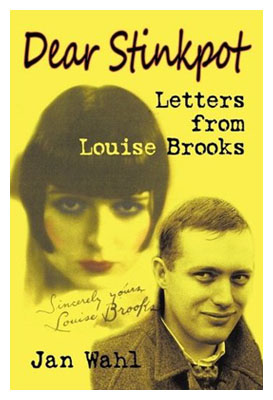

The answer may well lie in a book published earlier this year, Dear Stinkpot: Letters from Louise Brooks (BearManor Media). The recipient of the letters, and the editor of the book, is the celebrated contemporary children's book author Jan Wahl.

Brooks was a lot of things to a lot of people. To some, including the British theater critic Kenneth Tynan, "She was the most seductive, sexual image of woman ever committed to celluloid." Beauty, yes, and also brains. To the noted German film writer Lotte Eisner, Brooks was "An astonishing actress endowed with an intelligence beyond compare." To the Academy Award winning film historian Kevin Brownlow, Brooks was "One of the most remarkable personalities to be associated with films."

To Wahl, Brooks was a kindred soul with whom he corresponded for more than 20 years. Their roller-coaster friendship is documented in Dear Stinkpot. The title comes from Brooks' nickname for the author.

Wahl met Brooks in 1957. At the time, he was a poor graduate student and aspiring writer. Brooks, nearly twice his age, was then a mostly forgotten silent film star. The aspiring writer and the forgotten actress struck up an intense friendship, as well as a correspondence that spanned more than two decades. What drew them together was the desire to write.

The craft of writing, as well as books, authors, and the actress' current reading, are the dominant theme in Dear Stinkpot. There are, for instance, a handful of letters regarding Vladimir Nabokov. Wahl had taken classes with the Russian émigré at Cornell University and was an advocate of his fiction, including Lolita.

At the time, Brooks was working on a never published essay titled "Girl Child in Films." The actress read Nabokov's then (in)famous novel -- and disliked it, at first. Eventually, however, Brooks changed her mind about "Naby's" fiction. She came to appreciate his use of language and sense of satire. Brooks even hoped Wahl might be able to pass along to Nabokov her 1951 autobiographical short story, "Naked on My Goat." Brooks described it as her own version of Lolita.

As with Nabokov, Brooks at first disliked then came to appreciate the work of another contemporary writer. "The dialogue in Beckett is marvelous," she would write in one letter. Other writers, including Hemingway, take her punches, as would F. Scott Fitzgerald for other reasons. There is admiration for earlier authors like Thackery and Dickens. There are gossipy anecdotes about the Algonquin Roundtable writers who hung out in her Ziegfeld Follies dressing room. And there is a consideration of Leslie Fiedler's once seminal Love and Death in the American Novel.

Despite a continuous exchange of letters, it wasn't easy being Brooks' friend. (Elsewhere, she once famously wrote, "I have a gift for enraging people, but if I ever bore you, it'll be with a knife.") And here she admits, "The MAD AT BROOKS CLUB is a seething kettle."

The first letter in this collection begins, "If you care to be my pen pal, I'll thank you not to write on both sides of that thin paper." In later letters, Brooks' pointedly challenges Wahl's early efforts at getting published (his first book, Pleasant Fieldmouse, with illustrations by Maurice Sendak, was published in 1964) , knocks his literary heroes, and occasionally comes off somewhat snarky. Apologies would follow, as would Brooks' homemade fudge.

But along with the challenges were the rewards. Brooks could be witty, whimsical, profound, and endearing. And fascinating. What movie lover (and Wahl was that, as well as a collector of vintage films) wouldn't want to receive letters detailing meeting Jean Harlow, how Lillian Gish acted with her hair, personal observations of Chaplin, Garbo, Buster Keaton and Clara Bow, critiques of films and film makers, critiques of film historians, and the admission that her favorite actor was Ronald Colman.

Only occasionally would Brooks reference her own work, her now immortal performance as Lulu in G.W. Pabst's Pandora's Box, and her still highly regarded roles in Diary of a Lost Girl, Beggars of Life and other films.

There were other epistoltory discussions. About her finances: CBS founder William S. Paley gave her a monthly allowance, in remembrance of their brief affair decades earlier. About religion: Brooks converted to Catholicism for nearly a decade and read various mystical texts including works about Saint Teresa of Ávila.

And about dance: especially Isadora Duncan. Apparently, Brooks saw the legendary dancer perform, most likely in the early 1920's when she was still a teenage member of the Denishawn Dance Company alongside Martha Graham and under the tutelage of Ruth St. Denis and Ted Shawn. In the early 1960's, Brooks was considering the subject of dance while working on a never finished essay on women and movement. One of Brooks' singular observations was regarding Duncan's large flopping breasts.

Wahl has written about his friendship with Brooks in earlier articles scattered in various newspapers and magazines. There is also a substantial piece about the actress in Wahl's engaging book of autobiographical essays, Through a Lens Darkly (BearManor Media, 2008).

However, Wahl's new book, Dear Stinkpot: Letters from Louise Brooks, is the most detailed and telling portrait yet of their friendship. The story of their friendship as revealed through these letters -- and in Wahl's worthwhile commentary interspersed throughout -- is the story of two writers developing their craft. It is a revealing look at the later years of one of the remarkable personalities of the 20th century, and it suggests the kind of material which might be found in the newly unsealed journals.

Thomas Gladysz is an arts journalist and author. His interview with Allen Ginsberg on the subject of photography is included in Sarah Greenough's "Beat Memories: The Photographs of Allen Ginsberg" (National Gallery of Art, 2010). And recently, he wrote the introduction to the Louise Brooks edition of Margarete Bohme's classic novel, "The Diary of a Lost Girl" (PandorasBox Press, 2010). More at www.thomasgladysz.com.