by Naomi Ragen

In my forty-six years in Jerusalem, I have known two seasons: summer and winter. Summer comes gradually, the skies clearing of clouds, dyed in cerulean blue, the color of Arab doors and the Caribbean sea. The sun grows larger, moving closer, its light bleaching the vivid red Italian tiles of rooftops and the deep green of old pine trees like water dripping into a palette of watercolors. The air bakes, moisture-less, until the sun leaves, then dances, unburdened, its cool breezes whipping through open windows like a sigh of relief.

And then, without warning, the clouds reappear, turning silver then dark, steel grey as the winds bellow, whipping up little cyclones of bird feathers, desert dust, plastic bags, and the dry leaves of the rare deciduous trees among the olive, Jerusalem Pine, fig, and Red River Gums. Just when we have forgotten that such a thing exists, moisture falls miraculously from the sky after seven months of constant drought. We rummage through boxes for sweaters put away when it seemed as if they would never be needed again.

In my forty-six years in Jerusalem, I have known two seasons: relative peace and relative war.

Peace means going to the supermarket and standing behind an Arab family at checkout, listening to the camaraderie of Arabic chatter between clerks as they fill the shelves without feeling threatened. It means going to Liberty Bell Park on the Sabbath, breathing in the smoke of barbecuing lamb and shish kabob on a green lawn filled with Palestinian families who sit side by side with religious Jews, watching their children go down the slides and climb the jungle gyms. It means walking home after midnight from a concert at the Jerusalem Theatre, humming the tunes, taking shortcuts through the dark alleyways towards home. It means sitting in an outdoor café on Emek Refaim street without guards checking your purse or anyone else's. It means stopping for a moment because you have the time and aren't in a rush to get inside behind a locked door--to listen to the sounds of birds singing their hearts out, your eyes scanning the sky for the colony of green parrots that have taken up residence and continue to thrive. It means getting on a bus and playing Scrabble on your iPhone the entire time, without having to look up at every new person that boards. It means not reading the newspapers or listening to the news for days.

War, like winter, comes swiftly, enveloping you before you know it. It means putting a knife and tear gas in your purse before you leave the house. It means looking warily at the workers who are renovating the apartment next door, hoping they will not want to get into the elevator when you do, hoping you will not have to offend them by being obvious by refusing. It means empty parks and empty playgrounds, and parents driving the short distance to school, clogging your parking space, to let off and pick up their kids. It means news is now a required drug that must be taken on the hour. Who has died? Who has only been injured? And what of the enemy? Did he escape? Was he captured? Or will he kill again? And what is the government doing? And what is the army doing? And what are the foreign media writing? Are they lying, or telling the truth. Why don't they ever tell the truth?

It means turning down a deserted alleyway in broad daylight carrying a bag of bananas and a baguette when suddenly a Palestinian appears. You look around, but you are alone. He is speaking to you, but you cannot make out the words. You stand still deciding how much time you have before he runs towards you with his knife. Would it be better to swing the bananas at him, or drop your bags and take out your knife? Before you decide, he raises his voice. "Where is the nearest grocery store?" he asks. And you exhale, tightening your grip on your bags. You answer him, your voice steady, off-hand. "Straight ahead and then," you point, but cannot remember if the word for that direction is right or left, your mind seared, blank. And you wonder if he has seen your fear, noticed you stopped walking towards him. And you wonder which of you should be embarrassed and ashamed by that.

It means getting on a bus, all your senses sharp, alert, sitting up straight, paying constant attention to the random movement of every passenger. Is his hair dark enough to be a Palestinian's? What is she hiding beneath her long, traditional dark coat? Should I be afraid? Should I get off the bus, and then tell people: I was on that bus, but I had a feeling, an instinct, and I got off....Or will I get off the bus and hear nothing, and feel foolish and cowardly for running away, for giving into fear until the season changes again.

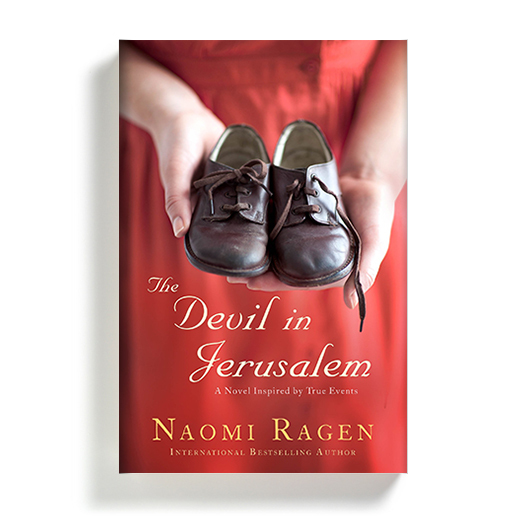

Naomi Ragen is the author of THE DEVIL IN JERUSALEM, available now from St. Martin's Press.