By Hannah Kohler

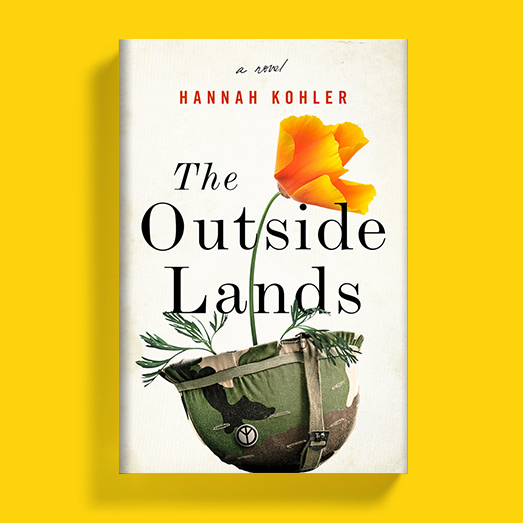

My novel, The Outside Lands, is set in 1960s San Francisco, during the Vietnam War. Siblings Kip and Jeannie Jackson are set adrift when their mother dies in an accident; Kip enlists to fight in Vietnam, and Jeannie joins an anti-war group that isn't what it seems. I'm not American—I'm British—and I was born after the end of Vietnam War. I'm often asked about the challenge of writing about a time and place with which I have no direct connection; and whether, as a woman, it was difficult to write about a young man's experience of war. But the central challenge of writing this novel wasn't that I'm British woman in her thirties; it was navigating the wealth of cliché associated with a war that has been the subject of so many representations in film, television, and print. We can all summon up images of the war—platoons wading through rice paddies, Hueys choppering over misty hills, napalm blazing the jungle, straw huts burning. The challenge was to navigate these clichés and get away from rehearsed portrayals of the war.

The problem with clichés is that they both hide and reveal experience: they have a relationship with the truth, but they get in the way of it. The visual clichés we associate with the Vietnam War have a root in experience—they are images originally seen in newspapers and on news bulletins and later reimagined in fictional representations—but they have been overused to the point that their original power and meaning have been lost. Where they were once surprising and evocative, they now come to their audience dead-on-arrival. But it's precisely their relationship with the truth that means that although clichés can become a trap for writers, we cannot ignore them entirely: we need to pay attention to them.

Because clichés are important, not just in how we understand the war now but also in how those who fought in the war understood it. In the course of researching my novel, I read dozens of American memoirs of the war, and was struck by how many of the young men sent off to fight in Vietnam carried their own set of clichés into the conflict—clichés of the American frontier, the western, cowboys and Indians and John Wayne. For these young men, the myth of the American frontier and its associated themes and ideas shaped their experience of the war and provided them with a language by which to articulate that experience.

The imaginative conflation of the American frontier with the American mission in Vietnam began with John F. Kennedy's Democratic National Convention nomination acceptance address in 1960. "We stand today," he said, "on the edge of a New Frontier--the frontier of the 1960's, the frontier of unknown opportunities and perils, the frontier of unfilled hopes and unfilled threats. [...] Beyond that frontier are uncharted areas of science and space, unsolved problems of peace and war, unconquered problems of ignorance and prejudice, unanswered questions of poverty and surplus." As Richard Slotkin brilliantly describes in Gunfighter Nation: The Myth of the Frontier in Twentieth-Century America, the mythic-historical story of the American frontier became the paradigm by which the American heroic endeavor to contain communism in Vietnam was nationally understood. There were parallels: a hostile wilderness; an unfamiliar indigenous enemy; the assumption of manifest destiny that seemed inherent in the Truman Doctrine and containment. Kennedy didn't live to see through all of his aspirations for America; but his frontier language reverberated through his successor's administration. President Johnson used the frontier metaphor to defend the Vietnam War, recalling Kennedy's commitment to defend "the frontiers of freedom" and telling LIFE magazine journalist Hugh Sidey that "he had gone into South Vietnam because, as at the Alamo, somebody had to get behind the log with those threatened people" (LIFE, October 10, 1969). Lawrence Ferlinghetti lampooned Johnson's folksy frontier references in his protest piece, Where Is Vietnam?, parroting "the President also known as Colonel Cornpone," saying "the New Frontier now truly knows no boundaries and those there Vietnamese don't stand a Chinaman's chance in Hell."

Sign up for more essays, interviews and excerpts from Thought Matters.

ThoughtMatters is a partnership between Macmillan Publishers and Huffington Post

The language of the New Frontier had a powerful hold on the imaginations of the young American men who went to fight in Vietnam. As Philip Caputo writes in his fine memoir, A Rumor of War, "we believed in all the myths created by that most articulate and elegant mythmaker, John Kennedy". Memoirs of the war continually draw on a frontier language that was commonplace among troops. Caputo and Nathaniel Tripp (in Father, Soldier, Son: Memoir of a Platoon Leader in Vietnam) repeatedly refer to combat zones as "Indian country"; in Dispatches, Michael Herr references the widespread practice of calling search-and-destroy missions "'[playing] Cowboys and Indians'". For a generation of young men raised on a steady diet of western movies and television shows, the idea of the frontier was both immediate and seductive. As Ron Kovic writes in his hard-hitting memoir, Born on the Fourth of July: "The whole block grew up watching television. There was Howdy Doody and Rootie Kazootie, Cisco Kid and Gabby Hayes, Roy Rogers and Dale Evans. The Lone Ranger was on Channel 7." For a teenaged Kovic, the impact of these western shows on his developing understanding of manhood was profound, and when the Marine recruiters visited his high school, "It was like all the movies and all the books and all the dreams of becoming a hero come true." And it wasn't only westerns that stoked these dreams of gun-slinging heroism, but World War II movies, too, which, as Kathryn Kane has noted, shared a great deal in common with their western counterparts (the opposition of civilization and savagery, and also a reliance on similar plots and values, and the habitual casting of John Wayne as hero).

Western movies and TV shows and their close relations, war movies, were so formative in imaginations of American boys that when they came to be standing on the New Frontier in Vietnam, they sometimes struggled to tell the difference between movies and reality. Michael Herr writes of his persistent difficulty in extricating his experiences from scenes depicted in the movies: "you couldn't avoid the ways in which things got mixed, the war itself with those parts of the war that were just like the movies". In his fictional memoir, The Things They Carried, Tim O'Brien writes: "you think of all the films you've seen [...] It all swirls together, clichés mixed with your own emotions, and in the end you can't tell one from the other." Caputo writes of his "Hollywood fantasies" in the field: "We are starring in our very own war movie" ... "I was John Wayne in Sands of Iwo Jima. I was Aldo Ray in Battle Cry."

Of course, the problem was that real experience didn't necessarily fit with the glorifying frontier clichés of good guys and bad guys, of conquering the wilderness and manifest destiny. Kovic and Caputo both write powerfully of their disillusionment with this American myth-making about a war they see as misguided and fraudulently sold. "He had been born on the Fourth of July, he had been their Yankee Doodle Dandy, their all-American boy," writes Kovic, but "[it] had all been one big dirty trick." Caputo writes: "I would never again allow myself to fall under the charms and spells of political witch doctors like John F. Kennedy." Cliché is powerful, but it is ultimately reductive, two-dimensional, and difficult to live in. And it is precisely this that I wanted to explore in The Outside Lands: the point at which one kid's internal mythic American frontier narrative--his movie-fuelled fantasies of Cowboys and Indians and war games and stock ideas of western heroism--comes up short against the disappointments and frustrations of his own real military experience. For Kip, this disillusionment leads him to commit a terrible and violent act of betrayal; and his sister, Jeannie, is left trying to pick up the pieces.

Hannah Kohler was raised on the south coast of England. She studied English and American Literature at Cambridge University and Business Administration at Oxford University. She began The Outside Lands during a Master's in Creative Writing at City University, London. She lives in London with her American husband and two children.

Read more at Thought Matters. Sign up for originals essays, interviews, and excerpts from some of the most influential minds of our age.