What do iron and fish have in common? Answer: Mauritania, a largely desert country of less than four million people in north-western Africa, is immensely rich in both. At the same time, most Mauritanians are poor. Last year, I spent several months doing research in Mauritania, and below will share some personal impressions from the edge of the global periphery.

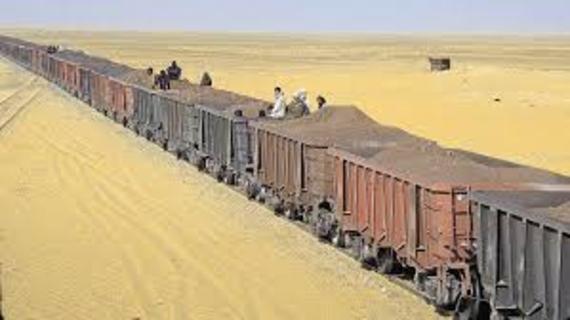

Deep in the Sahara, a cluster of small mountains rises above the depressing monotone of seemingly endless sandy plains. Some of them are more metal than rock, consisting of up to 75% iron, one of the highest concentrations in the world. Mauritania nationalized the iron mines in 1974, creating the state-owned monopoly company SNIM. Its workers blast the slopes to rubble, which conveyor belts then tip into waiting railway waggons. Zouerate, the mining town from which the train sets off, is a dystopian hellhole straight out of Mad Max that is as grim as it is hot. Every single day, the longest train in the world - according to locals, lengths vary between 80 and 150 waggons - slowly chugs its way across 700 kilometres of desert, until the line terminates at a special seaside quay. There, the ore is directly loaded onto a giant foreign ship, which subsequently carries the precious cargo of minerals away over the horizon, never to be seen again.

Image source: Le Figaro

Image source: Le Figaro

Mauritania's marine wealth largely vanishes across the very same horizon. The country has failed to develop a significant fishing industry of its own. The lion's share of the fish caught annually in what many believe to be the richest fishing grounds in the entire world are pulled aboard by foreign vessels. Most of that catch is taken straight to Europe or Asia. The amount of fish processed by the handful of small fishmeal factories is negligible. In total, the annual catch of half a million tons generates a mere 40,000 jobs inside Mauritania. To the south, Senegal translates a catch of similar size into at least 130,000 jobs. To the north, Morocco has turned its million-ton-a-year catch into a massive export industry whose turnover is projected to reach two billion dollars by the end of this decade. Nouadhibou, the sleepy backwater where the iron train line ends, doubles at Mauritania's main fishing port. Ramshackle corner shops stock tins of tuna 'made in USA', delivered from the wholesaler's by donkey cart.

Image source: Around the World in 80 Clicks

Image source: Around the World in 80 Clicks

Meanwhile, in the rich suburbs of the capital city of Nouakchott, which produces virtually nothing, giant villas rise out of the sand, and oversized SUVs cruise the streets. In the poor suburbs, families living five to a room have to pay for their drinking water by the barrel. The education system is so bad that 70% of Nouakchott secondary students are attending private schools, and as for the health system - well, when the president got "accidentally" shot not so long ago, he preferred to fly to Paris to receive treatment.

Image source: BBCIS

Image source: BBCIS

Yet, Mauritania works, sort of. Some people are very rich, many are hungry, but nobody is starving to death (as people did in my native Germany in 1948). The iron train runs across the Sahara every day, terrorists be damned. There's reliable electricity in the biggest cities (a feat that the entire U.S. occupation force in Iraq never managed to achieve). Many of the major roads are in a good state, and more are somehow getting built - albeit usually by international donors (the same donors never managed to complete major Afghan roads). People get up in the mornings, go about their business, and go to sleep without having to fear for their lives. Despite severe ethnic animosities, glaring inequalities, rampant corruption and nepotism, administrative narcolepsy, and a military-dominated polity that is democratic more in form than in substance, the country and its inhabitants keep muddling through, from one day to the next.

Interestingly, this lack of democracy and good governance coexists with a remarkable amount of freedom of speech. Mauritanian intellectuals and even opposition politicians repeatedly told me that "you can say what you like here". The country is both far more corrupt and far more politically free than its northern neighbour Morocco. Critical media outlets frequently run stories attacking the president, ministers, and top generals - but little if anything changes as a result. The watchdogs bark, the caravan moves on.

Why?

I'll share two stories that a friend told me. There's a power transformer on his street corner. Every rainy season, a pool of water forms around the metal box, and one or two by-passers get electrocuted. The problem could easily be solved by raising the transformer above the ground, but to the surprise of nobody, that somehow never happens. Nearby, there's a government school that has five classrooms. The school director has let out two of those rooms as private accommodation and pockets the rent. The mayor of the suburb, whose office is only hundreds of yards away, didn't find out for years, not least because the poor people who send their kids there never thought to complain.

To me, the moral of these stories is that Mauritania is what it is. Only two generations ago, most of its population lived in the desert or in small villages, where the very concept of government was unknown. We need to acknowledge that in this particular context, for the foreseeable future, Mauritania will not witness the emergence of Western-style accountability dynamics. If 'citizens' fail to hold their 'representatives' down the street accountable for what is happening in their children's school next door, they will certainly not start holding their distant national government to account for invisible, intangible, unimaginable billion-dollar revenue flows any time soon.

Image source: Africa Vernacular Architecture Data Base

Image source: Africa Vernacular Architecture Data Base

The naked truth is that the lengthy compliance reports of the national office of the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative and the eloquent press releases of the local Publish What You Pay coalition probably have a double-digit readership at best, and nearly all of that audience lives abroad. Essentially, these 'civil society groups' are foreign implants. Most of their activities are patently absurd, and the endless stream of paper they produce speaks a language alien to Mauritanians.

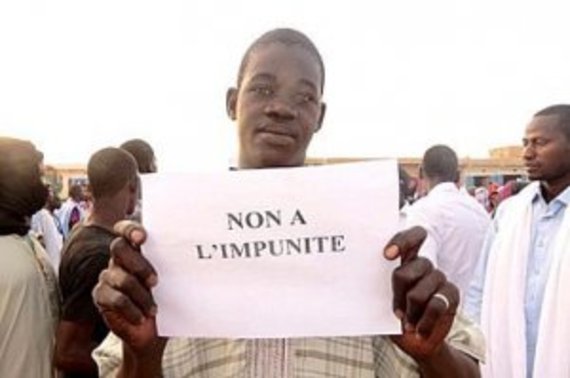

Compliance-tracking paperwork compiled by NGOs most certainly will not prevent the same few families who have been looting the state with impunity for decades from continuing to 'eat'. Increasing extractives revenue transparency will not increase accountability or reduce corruption in Mauritania. In this sense, the impact of these groups is zero. For every donor dollar invested, the theft of extractive revenues decreases by zilch. In terms of measurable impact, it is the least effective form of foreign aid known to man.

Nevertheless, these tiny groups are playing an incredibly valuable - if unquantifiable - role by accelerating the spread of novel ideas like transparency and rational-legal accountability throughout Mauritania, setting new standards and introducing useful tools along the way. "There's this organization called 'Publish What You Pay'," a lawyer in sleepy Nouadhibou told me, while complaining about a general lack of access to information in his country.

Publish what you pay? Access to information?!? Now, there's two truly radical new memes. You never know what might happen when they start to catch on.

Image source: UNPO

Image source: UNPO

Note: A different version of this post was published by the Global Anticorruption Blog in September 2016.