In 2010, after spending two years working and living in downtown Newark, New Jersey, I was ready to move to a neighborhood that did not require me to get in my car to buy decent produce or a half-gallon of milk. I wanted a neighborhood of convenience with restaurants, shopping and a mix of economically and racially diverse neighbors all within walking distance of my front door - a context different from my Newark neighborhood and that of my upbringing on the segregated south side of Chicago. During my search, I was encouraged by a friend to consider Harlem.

I had worked in Central Harlem in the late 1990's, and to be honest, I was hesitant about moving from one 'hood to another, uncertain whether the 21st century Harlem would offer me the urban lifestyle choices I was seeking. I took the train over from Newark to look at an apartment off Lenox Avenue/Malcolm X Boulevard. On my four-block walk from the subway to the apartment, I immediately noticed both the familiar and unfamiliar. I saw the Harlem I remembered from 1999 - bodegas, with the prerequisite bulletproof glass enclosures, an apartment building decorated with an array of old window treatments, and a few boarded up storefronts. But I also saw a changing Harlem as I walked by a Mediterranean bistro, a boutique flower shop, coffee café, and three bank branches. I even encountered a decent mix of black, brown and white faces - some gathered in front of the bodega, some pushing baby strollers, and some with book bags holding their parents hand. Upon turning the corner of Lenox and 120th Street towards my future home, I found a tree-lined block with handsomely maintained brownstones - reminiscent of walking into an Allan Jacobs "Great Streets" rendering. I let out a sigh of relief...."I think I'm going to like living in this Harlem!"

I've now been in the neighborhood over five years and every season brings about more visible change. New amenities, new neighbors, new complexions and new investments mix with old businesses, longtime neighbors, and the residual spaces of disinvestment. I have witnessed that this clash of people, place and program is sometimes met with a defiance, reluctance and resentment by lifelong Harlemites, and people of color more specifically. However, others in this same class are actually steering the change by operating businesses, investing in property, and producing innovative subcultures in art, technology and commerce. For example, many of the businesses I observed on my walk back in 2010 were owned by people of color, even one of the three bank branches. Yet and still, the gentrification of Harlem and the real and perceived impacts this change is having on longtime local residents - black folks - as well as new dwellers, is complicated to unpack and define.

So what narrative about gentrification are we to rely on to improve our understanding of neighborhood change. The narrative that relies on the statistics-based definition of gentrification, commonly used by city planners and measured by inflation in housing prices, increases in median household income, and changes in educational attainment, might confirm that Harlem is gentrifying. Between 2000-2010, median housing sales prices increased by 230%, while poverty rates over the same period declined from 36.4% to 28.1%. However, the real fear around data and gentrification is being fueled by Central Harlem's changes in black and white population. In 1970, black population represented 95.4% of residents and by 2010 had dropped to 55.9%. By contrast, white population over the same decades went from 4.28% to 16.1%, representing nearly a 400% increase. But to keep some perspective, you still see more black and brown faces living in Harlem than white. This data-driven story might indeed suggest that longtime Harlem residents are at risk.

Or what about the narrative of neighborhood change as presented in Joe Cortright and Dillon Mahmoudi's 2014 "Lost in Place" report highlighting that while Harlem is "rebounding" similar to the 100 out of 1,100 urban areas that saw reductions in poverty levels between 1970-2010, we must also acknowledge that this change may be a function of population increases in the neighborhood (backfilling four decades of neighborhood decline) rather than the upward mobility of long time low-income households as the overall number of people living in poverty in urban areas has doubled since 1970. This narrative also paints a questionable picture of an improved quality of life for local longtime residents. That being said, this report is really telling us we are obsessed with the wrong neighborhood change phenomenon - that instead of tracking the smaller percentage of urban areas that are truly "gentrifying", we should instead be more focused on why the other 1,000 out of 1,100 urban areas and its residents are no better off than they were 40 years ago.

As a confessed gentrifier, I prefer my own lived narrative of a changing Harlem - a story that uses a blended set of observed and data-driven indicators to establish the presence of economic (affordability) and cultural (racial composition and ethnic preferences) gentrification, and whether its outcomes have produced positive benefits for all. My narrative includes the presence of elderly black folks the have maintained ownership of their gorgeous brownstones mixed next to the black folks still inhabiting the many forms of low-income and public housing, some designed to be indistinguishable from historic row houses. My Harlem includes white mothers pushing baby strollers through the crowd of black men waiting online outside the barbershop while patronizing the adjacent hot dog street vendor, and young women of all races fearlessly jogging south towards Central Park after the sun has set, seemingly without fear.

But my favorite image is of a block of Lenox Avenue, between 125th-126th, that includes a bustling check cashing storefront, an African hair braiding shop and a French bistro, sandwiched between celebrity chef, Marcus Samuelsson's Red Rooster restaurant and Magic Johnson's first Starbucks franchise. In my narrative, this represents a perfect blend of affordability, multiculturalism, mainstream commerce and local entrepreneurial participation. But, it also depicts the vulnerabilities implicit in gentrification - what will it take to ensure that the commercial tenants serving lower income populations can withstand the rent increases brought on by the tastes and spending power of the emerging class.

The struggle to visibly and culturally maintain Harlem's history while accepting its long overdue reinvestment in manner where all can benefit - old and new, rich and poor - is very real, supported by both facts and lived experiences. I hope that my indicators of neighborhood change have revealed an emerging trend of inclusive ownership that I believe is an essential ingredient for just and equitable gentrification. Locally controlled property ownership, business ownership, ownership of cultural production and distribution is imperative. Supporting and doing business between these owners must also become an intentional practice.

It's time to shift the conversation from the rages of displacement towards the work of removing institutional barriers to space and capital, and expanding access to capital and networks so that more people of all income levels can make the same choices I made in 2010 to stay, return or relocate to Harlem.

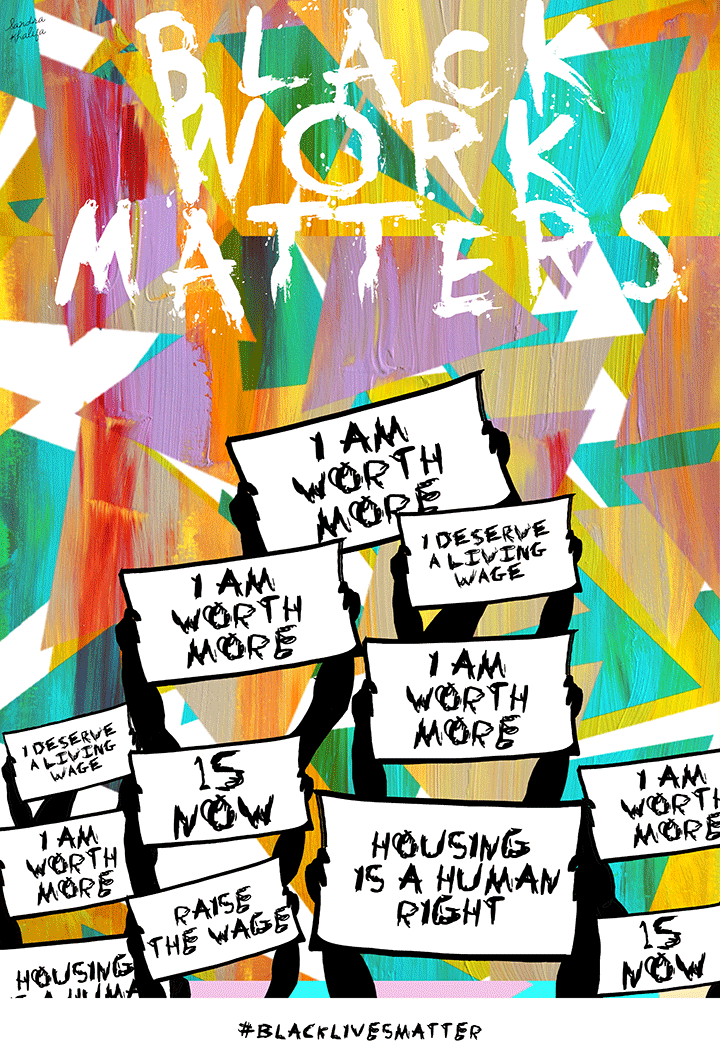

Illustration by Sandra Khalifa.

This post is part of the "Black Future Month" series produced by The Huffington Post and Black Lives Matter Network for Black History Month. Each day in February, this series will look at one of 29 different cultural and political issues affecting Black lives, from education to criminal-justice reform. To follow the conversation on Twitter, view #BlackFutureMonth.