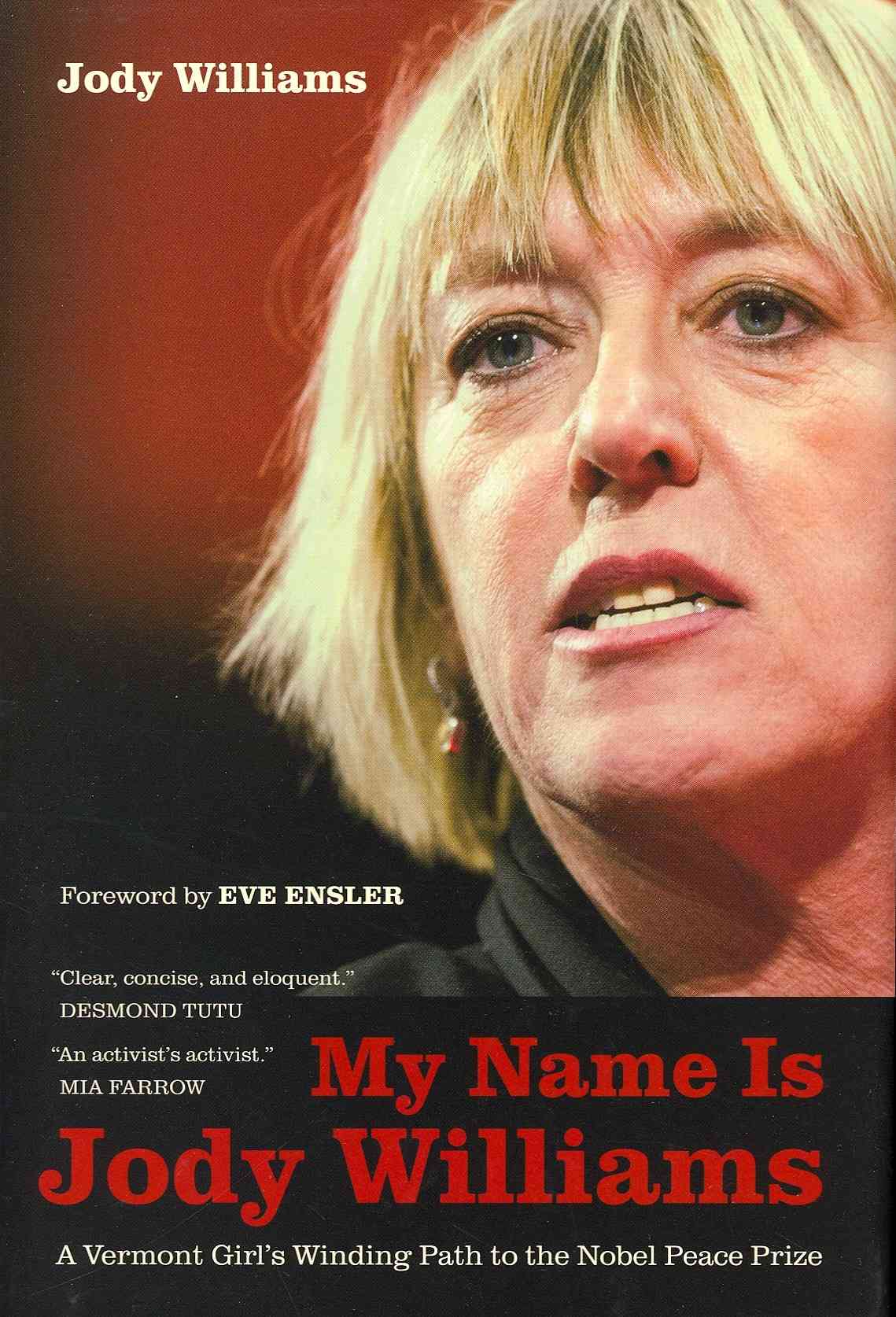

As America debates a possible military response to the Syrian government's use of chemical weapons on their own people, I've been reading the new book MY NAME IS JODY WILLIAMS, an autobiography by the bulldog American activist who was awarded the 1997 Nobel Peace Prize for her role in the campaign to ban landmines.

Land mines, cluster munitions, chemical weapons - all of these are categories of weapons that can't tell the difference between a soldier and a child and therefore maim and kill indiscriminately. They also share the distinction of having been very nearly eliminated through efforts led by civil society and people like Jody Williams, her husband Steve Goose of Human Rights Watch and many thousands of others. The catch of course, is that pesky phrase "very nearly" which unfortunately encompasses the fact that both the United States and Syria are among the nations that have declined to join the great majority of the world in banning land mines and cluster munitions. Unlike Syria, the U.S. is a signatory to the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC) but still has more than 2,000 metric tons of chemical weapons and has fallen behind on our timetable to destroy them.

I met Jody Williams a decade ago to interview her for my film Nobelity, in which she was a powerful advocate for the landmine ban and for the need of civil society to have a voice in policies related to what we collective refer to as Defense. When Jody helped found the International Campaign for Landmines (ICBL), there were tens of millions of mines in the ground in 80 countries, taking more than 15,000 new victims each year - most of them civilians and many of them children - and there were 180 million more landmines in stockpiles around the world.

Jody Williams in the film Nobelity

Two decades later, 160 nations are now parties to the landmine ban treaty, 44 million stockpiled landmines have been destroyed and the massive global trade in landmines has been virtually halted. Every nation in our hemisphere has signed or acceded to the landmine ban treaty with two exceptions - the United States and Cuba.

I was in Oslo for the 2008 signing of the Convention on Cluster Weapons (CCW) where Steve Goose reminded me that U.S. stockpiles of cluster munitions contain almost one billion sub-munitions. "When it ("an unexploded sub-munition) lays on the ground," Goose explained, "a child sees an attractive thing that looks very much like a toy."

I met one of those children, 13-year-old Ayat Syleinman, who was burned over 65% of her body when her little brother picked up an unexploded American cluster bomb dropped in Iraq in 2003.

Lest you think all this talk of banning weapons somehow flies in the face of our brave troops, I was very much dissuaded of that idea by an emotional conversation in Oslo with Lynn Bradach, the mother of an American Marine who was killed in Iraq while clearing cluster munitions dropped by his own country. Unlike other weapons, when a conflict ends, deployed land mines and unexploded cluster munitions are left behind and are lethal to civilian populations and the troops who work to clear them.

While we debate our nation's role as the enforcers of the proper morality of war and weapons of mass destruction, it might serve us to remember that our commitments - and lack of commitments - to global peace greatly help shape our image and standing in the world and our ability to address seemingly intractable problems through leverage other than military.

As Jody Williams reminds us in her book, "The United States spends more on its military and weapons systems than all the other nations combined." That's right, we are Number One... with a bullet. "The United States hasn't used anti-personnel land mines since the first Gulf War in 1991," Williams writes. "It has also destroyed millions of stockpiled landmines. The primary issue is that the U.S. military doesn't want to bow to civilian influence in terms of which weapons it can and cannot use."

Or as she says in Nobelity, "They're concerned about the slippery slope."

Thankfully, the U.S. agreement to the ban on chemical weapons and has resulted in the destruction of 90% of our declared 25,0000 metric tons of chemical weapons. That leaves almost 2,500 metric tons of CW remaining in the U.S. and we are now a decade behind schedule in destroying these weapons and agents. The list of U.S. chemical weapons stored at PUDA (near Pueblo, Colorado) includes Blister Agents, Nerve agents (Sarin, VX and three others), (Sulphur Mustard and three others), as well as six types of blood and choking agents.

Declining to sign the ban on landmines and cluster munitions - and falling behind on our commitments to the Chemical Weapons Convention - reduces our standing to play a highly-respected role in reducing conflict. As is now clear in Syria, the best time to convince a nation to ban chemical weapons and other indiscriminate killers is not when a leader has nothing to lose, but when we all have something to gain. It's almost impossible to know for certain what we will gain by an attack, but it's clear that there is much we could lose.

Jody Williams' book is an up close and personal account of how a handful of people were able to unite a coalition of 1,400 civil organizations and 160 countries in the work to accomplish what very few believed was possible. As Congress debates and Kerry lobbies, we might do well to remember the important role of civil society in shaping our common world.

I was introduced to Jody Williams by another Nobel Peace laureate, Desmond Tutu, whose blurb for Jody's book says, "Jody Williams is a grassroots activist at her heart, committed to empowering all individuals to believe in their ability and their right to contribute to a better world."

Tutu has been recently pointing out the tremendous need for both dialogue and humanitarian relief in Syria. The crisis in Syria, Tutu writes, needs be resolved through "human intervention, not military intervention."

With no good military options that don't hold considerable risk for the region, with Assad's forces having killed 100,000 Syrians (an estimated 7,000 of them children), and with growing fear of the political make-up of who might replace Assad, maybe it is time to listen to Desmond Tutu, Jody Williams, and many other activists for peace. Maybe it is time to open lines of communication aimed at ending this dreadful civil war. Before it is too late, maybe it is time to talk.

Turk Pipkin

The Nobelity Project

* In 111 years, the Nobel Peace Prize has been awarded to only 15 women. Jody Williams is currently the chair of the Nobel Women's initiative, which unites six women Peace laureates to advance the causes of nonviolence, peace, justice and equality.

Jody will be signing her new book and speaking about her work at Bookpeople in Austin, Texas at 7 p.m. on Saturday, September 7.

My Name Is Jody Williams: A Vermont Girl's Winding Path to the Nobel Peace Prize