UPDATE: This interview was done on May 19, 2013 shortly after Efraín Ríos Montt had been convicted of genocide and crimes against humanity. In a recent development on May 20, 2013, Guatemala's highest court overturned the genocide conviction of the former dictator and ordered that all trial proceedings be voided going back to April 19, 2013. It is unclear when the trial may restart.

Documentary films can be eye-opening, thrilling, informative, maddening, and impactful. But Pamela Yates' film When the Mountains Tremble has gone beyond any filmmaker's highest hopes. Shot in the early '80s amidst a brutal dictatorship in Guatemala, her film was intended to document the government's repression of the Mayan population and to shed light on a murderous civil war that the U.S. was funding. Little did she know that an interview with the General of the army, Efraín Ríos Montt, who rose to power through a coup would serve as evidence in a genocide trial against him more than 30 years later.

When the Mountains Tremble was Pamela Yates' first feature film and has made an indelible mark on her life. In 2003, she was asked by an international attorney to review the outtakes from an interview with Ríos Montt as part of an investigation on a genocide case. Fast forward to May of 2013, the entire interview was shown in court and admitted as evidence in the trial against the General. Shortly after, General Ríos Montt was found guilty of genocide and crimes against humanity.

Guatemala's search for justice and the thrilling story of using her old footage as evidence unfolds in her most recent film Granito: How to Nail a Dictator. It premiered at Sundance in 2011 and is part human rights film, part forensic investigation, and part reunion as Yates returns to the country and people she had connected with several decades in the past.

This year Yates has come full circle and returned to Guatemala once again to witness Ríos Montt's trial. She plans to make a new film, the final piece in a trilogy of documentaries on Guatemala's brutal past and its hopeful future now that impunity is a fading memory.

I caught up with Yates via email as she was in Guatemala filming the genocide trial. She talks about using the power of film to tell meaningful stories and push for social change. She also recounts what it was like to be in the courtroom as General Ríos Montt was sentenced to 80 years in jail.

Do you consider yourself a filmmaker or a human rights activist who makes films?

Yates: I'm both an artist/filmmaker and a human rights defender. I'm a storyteller who uses all of the beauty and power of cinema to tell tales of human struggles for positive social change. Like a human rights lawyer who uses the law to rectify wrongs, I use film storytelling for the same effect.

What is your ultimate goal when making a human rights film? Are you simply documenting events, raising awareness, or are you advocating for change?

Yates: I'm artfully documenting a story and always showing a way forward. That's why our films are feel good human rights films. Like good human rights defenders we have an optimistic outlook though we tell difficult stories. And if you make a great film full of emotion, of pathos, people want to continue to know more, to work harder. So our feature length documentary films are the flagship for a whole ecosystem of media offerings. With Granito: How to Nail a Dictator we created a companion digital project, a public online archive of memories from the war, where anyone can go and upload or access a memory. This is so important in Guatemala where the sole genocide that happened in the Americas in the 20th century is not taught in high schools or colleges. It's here: www.granitomem.com.

And we have shorts for classroom use, micro-docs, study guides and lesson plans. We've made a commitment to produce all materials equally in Spanish and English.

In Granito you talk about the process of revisiting the old footage and outtakes from your film When the Mountains Tremble. Often, the passage of time can change our perception of certain events. Was there anything that stood out at you or that seemed different when you looked at the old footage again?

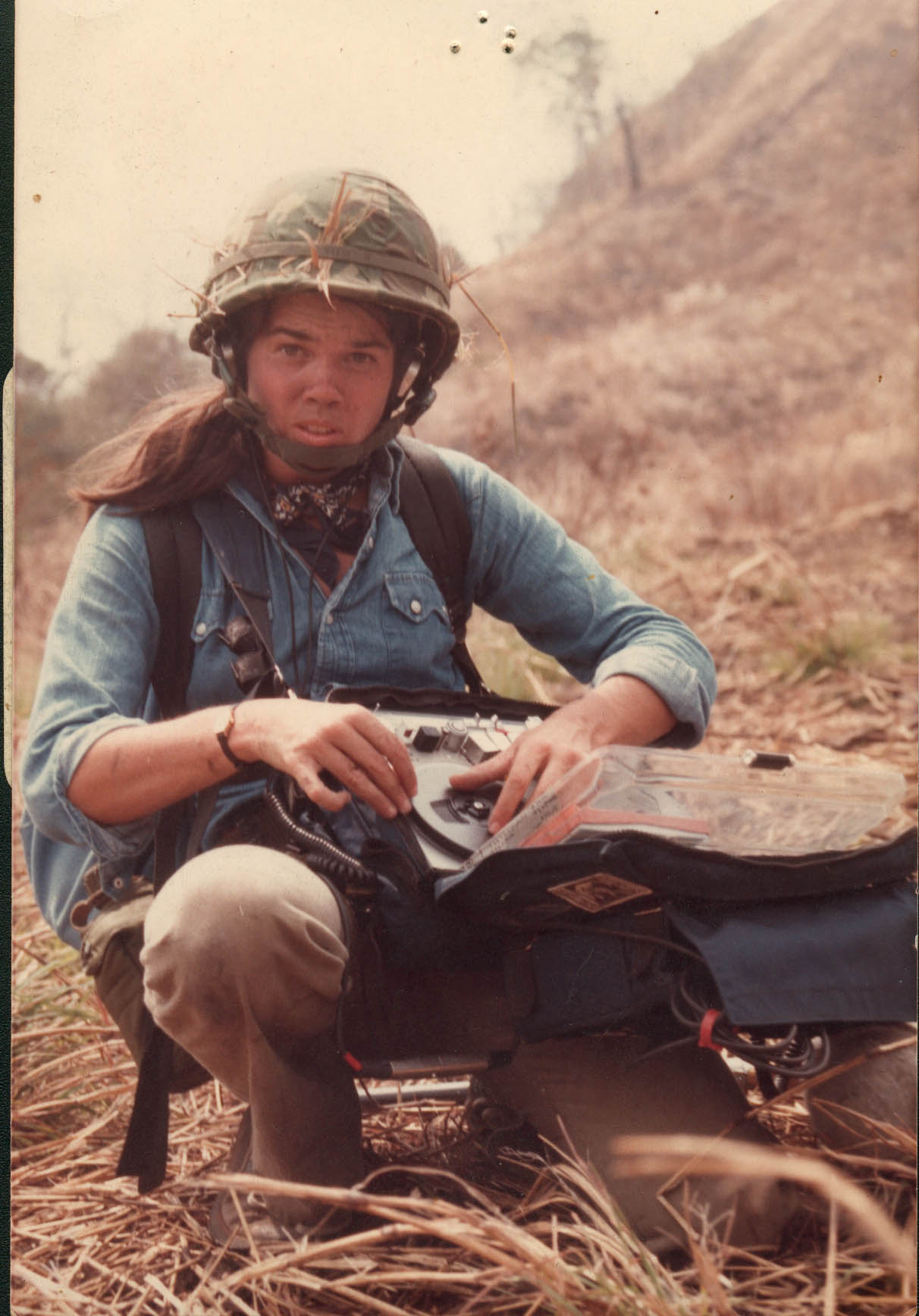

Yates: When you make a documentary film, after many years the only thing you remember is what you put into the film, not what you took out. So after 25 years, going back and looking at all the 16mm outtakes, was a true revelation. And then, in each shot I was looking at my 25 year younger self. Because we shot double system (16mm film and 1/4 audio tape) back then, and the cameraman had to turn to me to get a sound slate for each shot. That gave us the idea for me to be the witness in Granito. It gave the viewer the opportunity to actually see outside the framing of the 1982 prequel When the Mountains Tremble. And as the first person witness, it gave me a way to add the layer of filmmaking to the story -- a way to share my experiences from over 3 decades, with the next generation of engaged filmmakers.

Yates: When you make a documentary film, after many years the only thing you remember is what you put into the film, not what you took out. So after 25 years, going back and looking at all the 16mm outtakes, was a true revelation. And then, in each shot I was looking at my 25 year younger self. Because we shot double system (16mm film and 1/4 audio tape) back then, and the cameraman had to turn to me to get a sound slate for each shot. That gave us the idea for me to be the witness in Granito. It gave the viewer the opportunity to actually see outside the framing of the 1982 prequel When the Mountains Tremble. And as the first person witness, it gave me a way to add the layer of filmmaking to the story -- a way to share my experiences from over 3 decades, with the next generation of engaged filmmakers.

Granito is very different from your other films because you are a central character in the story. What did it feel like to be in front of the camera? Was it challenging?

Yates: It was difficult to get the balance right between telling my story of how I made choices in life, in filmmaking, with the greater story of Guatemalans' 30 year quest for justice for the genocide committed there. But with the team of filmmakers and writers -- my partners Peter Kinoy and Paco de Onís -- we worked hard on the writing and the crafting of the story. In Act 1, I tell the story of the making of When the Mountains Tremble in 1982. But by Act 2 and Act 3, the Guatemalans take over the story and my story, their story, our destinies are interwoven.

You are currently in Guatemala. Can you explain what it is you are doing there?

Yates: I was filming the entire trial of the dictator in Granito: How to Nail a Dictator, General Ríos Montt. He was being tried in a Guatemalan court of law and my filmed interview with him from 1982 was shown in its entirety by the Prosecution as it rested its case. It's the first prosecution of a former head of state in his own country on charges of genocide. So it's an enormously significant case in Guatemala, in Latin America and throughout the whole world. On May 10, 2013 Ríos Montt was convicted of genocide and crimes against humanity and sentenced to 80 years in prison. I'm now making the third feature length film in the Guatemalan trilogy about this as well as releasing a series of short filmed moments from inside the courtroom called Dictator in the Dock/Dictador en el Banquillo and releasing them in Spanish and English here: www.granitomem.com.

When you initially went to Guatemala in the 1980s to film When the Mountains Tremble, you set out to make one singular film about the ongoing military conflict there. With Granito you have now made two films about this moment in Guatemala's history. And now you are back in Guatemala filming the trial of Ríos Montt. What about this story has compelled you to keep the camera rolling?

Yates: It's Guatemala and its incredible beauty and spirituality. It's a majority indigenous country and physically it is breathtaking. I think my 30 year friendship with Rigoberta Menchú always brings me back too. But it is the people of Guatemala who have never given up their spirited quest for justice for over 30 years that make for such compelling documentaries. Destiny doesn't control your life, but it does place you on a path. It's how you walk down that path that determines stories I tell.

Witnessing the trial and listening to graphic testimony must have been difficult. Were there any stories in particular that affected you more deeply than others?

Yates: One of the most difficult moments in the trial were the Maya Ixil women who testified to being raped and the objects of sexual violence and torture. It went right to the heart of the genocide claim, that the Army, the state itself killed them and their children in order to eliminate in part or in whole their community. To hear their testimony of fetuses being ripped from the wombs of mothers was utterly inhuman. These women covered their heads and faces in brightly woven shawls in order to protect their identity. Guatemalan feminists flooded the courtroom and covered their heads in the same shawls and a show of solidarity and support.

After the prosecution had put forward nearly 150 eyewitness survivors, expert witness and military documents, to rest their case, they projected the interview with General Rios Montt that I did with them in 1982 where he claims command responsibility over the Armed Forces. This was critical to prove the genocide case, because Ríos Montt's defense is that he did not know what was happening, what his officers were doing in the field. In fact they were carrying out his orders. To see the 86 year old Ríos Montt looking at his 30-year-younger self projected in the courtroom was stunning. Now he looks old and weak, but in the film footage he looks strong, vital, arrogant. It was a good reminder of the absolute power he wielded as a ruthless General in 1982.

After spending almost two months filming the trial what was your emotional reaction when hearing the verdict?

Yates: I was elated, I was satisfied, I was glad to be there and share the moment with all the Guatemalans and their international allies who had worked so hard for this day to come. Upon hearing the verdict, people spontaneously stood up and shouted "Justicia! Justicia!" and then began singing this gentle song by Guatemalan poet Otto Rene Castillo:

Aquí no lloró nadie

Aquí sólo queremos ser humanos

Comer, reír, enamorarse, vivir

Vivir la vida no morirla

Here, no one cried

Here, we only want to be human

Eat, laugh, fall in love, live

Live life not die

Now that the trial is over, what's next for you?

Yates: I will work on editing the new film on the Ríos Montt trial and we are in post-production on a new film Disruption about economic human rights. It's a good news story coming from Latin America.

Your films cover topics that can sometimes leave the viewer with a heavy heart. I imagine it must have the same effect on you. Do you ever seek therapy in watching films of a completely different caliber - something like The Hangover 3?

Yates: I'm an eclectic and avid filmgoer. I try to see everything from romantic comedies to blockbusters to art house films, world cinema and documentaries. I truly value the cinema experience, the tribal gathering in the dark to watch something larger than life. I like to sit in the first row with no heads in front of mine, and become one with the screen. I always stay for the complete credits so I can linger in the film's story just a little longer.

The rise of digital technology has made it so that anyone can pick up a camera and make a movie. But, it seems harder for filmmakers to make a living off of making films. You have had a long and fruitful career as a director. Any advice for young documentarians?

Yates: The digital revolution has had a democratizing effect. Now anyone can be a filmmaker, but to be a good filmmaker is as hard as it ever was. Everyone has access to a pen and paper, but to be a great writer is difficult. Still, we now have a much bigger pool of potentially great filmmakers. And I think that is why we are seeing an explosion in the documentary filmmaking genre. I think it has gotten easier to make a living from our films, from our filmmaking. There are many more jobs in nonfiction filmmaking field and more creative DIY opportunities to get the films seen. My advice to emerging documentary filmmakers would be: try to find other people, a group, a cooperative that you can work with. Film-making is hard and lonely and decidedly unglamorous. Find like-minded souls and share the joy and the misery. Celebrate your victories and mark your defeats. Ultimately documentary filmmaking is not a job, it's a calling.

When the Mountains Tremble and Granito: How to Nail a Dictator are streaming for free on PBS.org through May 24 in both English and Spanish. Later this month both will be released on Netflix and iTunes.

This interview originally appeared on LatinoBuzz, a weekly feature on Indiewire that highlights Latino indie talent and upcoming trends in Latino film. Follow @LatinoBuzz on Twitter and Facebook.