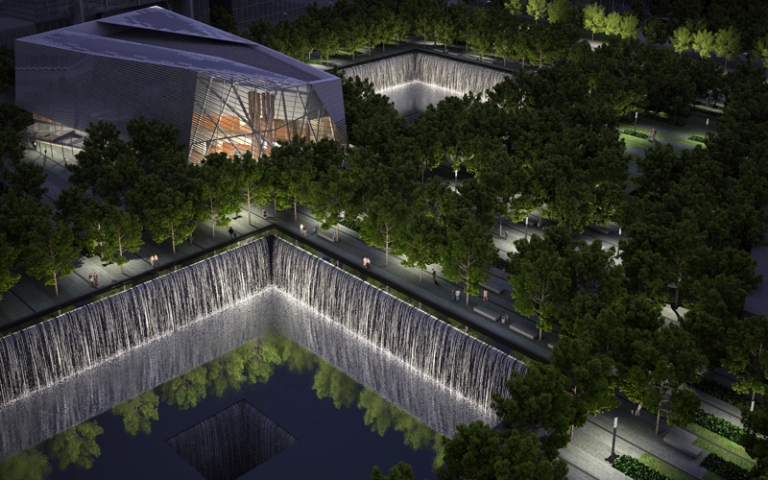

Rendering of the future National September 11th Memorial and Museum (photo: courtesy of Squared Design Lab/NS11MM, and the museum)

Increasingly, museums are about understanding the impossible, the epic, and the most perplexing and violent issues of our time. No one knows this better than Alice Greenwald, Executive Vice President for Programs and Director of the National September 11 Memorial Museum. Our future 9/11 museum is still just a giant hole in the ground and in our hearts, but it is very much underway ...

Third Screen: What will we see when we approach what was once the site of the World Trade Towers?

Greenwald: Entering from the north, off Fulton and Greenwich Streets, you'll move through a forest of 400 trees towards an elegant museum entry pavilion. From a distance, you'll see two massive steel structures standing inside a glass atrium that just tower over you -- remnants of two columns that were once part of the World Trade Center towers.

Third Screen: Steel from the actual buildings?

Greenwald: Yes. The World Trade Center towers were clad in aluminum and in the destruction much of the aluminum blew off, but because of that, the steel underneath was not as heavily damaged. One of the unique elements of the Museum will be the presentation of massive artifacts, huge pieces of steel, large vehicles. It will not be a typical museum in terms of the materials we have available to present.

Third Screen: Tell me about what the designers have named the "void."

Greenwald: You're talking about the Memorial Plaza and Memorial pools. They are the work of architect Michael Arad, who together with Peter Walker Partners -- the landscape architects -- won the competition for the Memorial design back in 2004. Michael's vision was to take the verticality of the space where the Towers once stood and accentuate the absence of the vertical now, as a way to encourage contemplation of the even larger and almost unimaginable loss of human life at this site.

Third Screen: There are waterfalls around us but we'll also look down at water that falls away from us at ground level?

Greenwald: Yes. He inverted the verticals. There will be two acre-sized pools. Each will be located where one of the Twin Towers once stood. Waterfalls will drop 30-feet and then fall again into a square void at the center of each pool. You can't see where the water ultimately goes. It disappears into the center void. When they're built, these may turn out to be the largest man-made waterfalls in the western hemisphere, if not the world. The names of the victims of September 11th, not only those who died at the World Trade Center, but those who perished aboard Flight 93 and at the Pentagon on 9/11, as well as the six victims of the World Trade Center bombing in 1993, will be arrayed around the parapets of this pool.

Third Screen: How does a project like this begin?

Greenwald: When I arrived in Spring 2006, I brought together a core planning team. By that Fall, we had on board a museum educator, curator, historian and program advisor, exhibition developer, and a creative director. We set about finding design partners by issuing an RFQ -- a request for entries. We had sixteen responses from design groups around the world - - from England, France, several from the United States, two from Canada, one from Germany. That was a lesson in itself. 9/11 is as much a global event as a New York and American event. The choice was based on the quality of the submission and the dynamic of our interactions with the design firm, because working with a designer on a multi-year project of this importance and scope is like a marriage. The design group we chose, Thinc with Local Projects, helped us to see the potential through new eyes.

Third Screen: What did they present?

Greenwald: We gave them a timeline, critical content to be addressed, and a choice of visual material to draw from including a massive and provocative piece of "impact steel" from the North Tower. When the hijacked Flight 11 plane entered the building, the steel columns literally bent back like the fingers of a hand. What the winning team delivered was a way of presenting the material that we hadn't thought of. They opened our eyes to the possibility of our narrative -- that was the big thing. We enjoyed talking to them, and their submission was outstanding, but in the end what made the difference is that they made us see our own material and content with new eyes and richer understanding.

Third Screen: What did they do with the impact steel?

Greenwald: We assumed it would be presented on the ground , on some kind of stand or base, or simply lying on the floor as a remnant. But what they did -- and this is what made us look twice -- is they mounted the impact steel vertically above the visitor's head. This gave it a reverberation of the actual history. Metaphorically, they put it back. The scale is enormous and you feel it. It was just one of those powerful ingenious moves on their part that made us choose them. Another aspect of our selected designer's portfolio that really impressed us was what they had been doing in South Africa. The design principal has worked several years on the Freedom Park project in Pretoria. Many of the issues of that memorial and museum project are comparable to ours. How do you deal with a charged history of atrocity and mass murder at the very site where these events took place? And in a museum setting that is also a memorial and an educational institution for the future? And in a way that works for generations who did not experience the events? How do you accommodate the remains of victims in a meaningful and appropriate way?

Third Screen: How do these new "museums of humanity" differ from traditional museums?

Greenwald: Let me give you a quick overview of the history of museums. There were no museums as we know them before the 19th century. There were cathedrals, royal treasuries, but you didn't have public museums until you had the spoils of Colonialism -- the Elgin marbles, for example. Museums began as cabinets of curiosity, accumulations of fascinating specimens and artifacts from around the world -- the World's Fair in Chicago, for example. Museums were places of education and connoisseurship, where the curator, the expert, whether in art, history, or science, distilled the information so that the visitor would be properly educated as a result of the connoisseur's knowledge. One went to a museum to learn what one needed to know to be well-educated - -- to know the "canon," what "good" art is, for example. It was very top down. In the latter half of the 20th century, it all changed.

Third Screen: Museums changed? We don't think of them as places of change.

Greenwald: A democratic movement began in museums that attempted to reach out to a wider audience, to create more "popular" presentations. King Tut, the first of the "blockbuster" museum exhibitions, is a good example from the 1970s. And gradually, museums began to focus more on their communities and issues of civic engagement, challenging the visitor to become not simply a viewer, but a part of the exhibitions, to ask questions and not necessarily to get answers. For example, when Shaike Weinberg, the founding director of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, came on board, he came out of an unusual professional background - one that wasn't dependent upon a collection of objects to tell its story.

Third Screen: No longer a bunch of gilt frames, marble columns, and glass boxes?

Greenwald: Shaike had created the Museum of the Diaspora in Tel Aviv, Israel. This was a museum without artifacts. A museum without a collection? Unheard of. He had directed the Tel Aviv municipal theater and had come from the world of computer science. He brought those experiences together to dynamically tell a story in three-dimensional space. As a result, the visitor moves through the story rather than sitting in an audience. The Holocaust Museum is also a little like walking through a movie, and the high proportion of film footage screened in the presentation reinforces this, but there are strategic and extremely powerful artifacts as well to carry the narrative along.

Third Screen: What happened next?

Greenwald: Now, increasingly, there are peace museums, museums of conscience, and memorial museums that use their subject matter to inspire deeper reflection, greater civic awareness, and even political advocacy. In a complicated and increasingly globalized world, you have the need to become politically fluent. In response, museums have become a place for engaging difficult and complicated social issues. The Museum of Tolerance in Los Angeles is an example. There, visitors are challenged to make ethical choices about how they would respond to specific situations. Our project takes a lot of cues from the various new developments in the museum business but we have a particular set of challenges.

Third Screen: What is the direction for the museum now?

Greenwald: We are building three kinds of institutions in one. This is a memorial, first and foremost. But, it is also an archaeological site. And, it is a museum. We have the obligation to commemorate those who perished and to provide public access to the authenticity of the site, and we also have to honor the educational obligation to tell the story of what happened. What we won't do is create an immersive experience. Our approach is to use the first person testimony of eyewitnesses, including the extraordinary voice mail recordings of people in the buildings and on the planes, cockpit recordings, and so forth, so visitors can encounter this history in a meaningful and immediate way. We won't replay it. We will evoke it.

Third Screen: What are your challenges?

Greenwald: Time and location. Close proximity to when the events occurred and the fact that we're still trying to understand it, still figuring it out, still in the middle of the story. We're at a site that is located in one of the most densely populated business districts in the world. The city is going on around us, and we want to construct a precinct of memory. There are equally valid pressures to rebuild and revitalize the World Trade Center site and to mark the events that took place here. And, then there is the additional challenge that this is the very place where people were killed. That reality is part of the very nature of this place.

Third Screen: Wall Street is not a green place. You're making a green place.

Greenwald: Yes, the Memorial Plaza will be a refuge, a densely-forested park. Each of the 400 beautiful trees is itself a symbol of rebirth, of the cycle of life.

Third Screen: What is available to people at this point?

Greenwald: The virtual museum is open. On our Web site at www.national911memorial.org you can see our scope, the kinds of things we'll have at the physical site. You can listen to oral histories, and you can see some of the artifacts and memorabilia we are collecting for the Museum. We have a "Story Corps" initiative, where we are attempting to honor every victim through individual remembrance interviews. And we recently launched an educational interview series, "Exploring 9/11," which offers fascinating perspectives on the lead-up to the tragedy and the world afterwards from people like journalist Lawrence Wright, author of The Looming Tower, and professor Bernard Haykel, who teaches Islamic law at Princeton. I've heard it is one of the most downloaded parts of the Web site these past few weeks. And for people who want to become involved and help support the building of this national tribute, we have made it possible to buy cobblestones or paving stones which will line the 8-acre Memorial Plaza.

Third Screen: It will in a central way remain a grave site for the victims where their families can come and mourn?

Greenwald: For many families, friends, and former colleagues of victims who perished at the World Trade Center on 9/11 and in 1993, this will certainly be a place to come to, to mourn their loss, to pay respects, and to remember. We have engaged a number of family members in the work of imagining the Memorial Museum, and we've been fortunate to have family members deeply engaged in the process as partners who challenge us and demand from us that we remember certain things. There is, of course, a wide spectrum of response. But, one thing we do as an institution, regardless of the position of family members, is we view them all as particularly privileged voices in this history. We have an obligation to be respectful, to honor them, while recognizing that a memorial of this nature is both for them and for others. Ultimately, it is for the future, and we have an obligation to those who didn't experience this history personally. We need to teach, and we need to ask people to think about what happened, and about the kind of world we want our own children and grandchildren to inherit.