Just caught up with film critic Elvis Mitchell as he and renowned portrait photographer Timothy Greenfield-Sanders get ready for the television premiere of "The Black List: Vol. 1," their first journey as documentary filmmakers together (Monday, August 25th at 9 pm ET on HBO). Who knew that Kareem Abdul-Jabbar was a journalism major who has written several books? Or that Serena Williams is still waiting for reporters to talk strategy with her rather than just fluff? Or that the Rev. Al Sharpton has a lot to say about things other than politics? "There is a hunger out there," Mitchell told me, for African Americans to be seen and heard as they are, right now in the 21st century, and an "impatience" to get beyond the narrow representations we still see in media. What to do? In May 2006, over a lunch and with much scribbling on napkins, the two embarked on a film in which Greenfield-Sanders' photographs "speak." You stare at them. They stare at you. And slowly, skillfully, the stories and the magic unfold. No on-camera interviewer. Mitchell is edited out of the final cut. No themes. No cross-cutting. So why does it lift you up, make you cry, or if you see it at a film festival as many have across the country these past several months, make you want to just sort of stay there and talk all night? Elvis Mitchell has some thoughts.

Just caught up with film critic Elvis Mitchell as he and renowned portrait photographer Timothy Greenfield-Sanders get ready for the television premiere of "The Black List: Vol. 1," their first journey as documentary filmmakers together (Monday, August 25th at 9 pm ET on HBO). Who knew that Kareem Abdul-Jabbar was a journalism major who has written several books? Or that Serena Williams is still waiting for reporters to talk strategy with her rather than just fluff? Or that the Rev. Al Sharpton has a lot to say about things other than politics? "There is a hunger out there," Mitchell told me, for African Americans to be seen and heard as they are, right now in the 21st century, and an "impatience" to get beyond the narrow representations we still see in media. What to do? In May 2006, over a lunch and with much scribbling on napkins, the two embarked on a film in which Greenfield-Sanders' photographs "speak." You stare at them. They stare at you. And slowly, skillfully, the stories and the magic unfold. No on-camera interviewer. Mitchell is edited out of the final cut. No themes. No cross-cutting. So why does it lift you up, make you cry, or if you see it at a film festival as many have across the country these past several months, make you want to just sort of stay there and talk all night? Elvis Mitchell has some thoughts.

Third Screen: How did you and Timothy Greenfield-Sanders work together?

Mitchell: Most of the interviews were shot at Timothy's studio, which is at his home. When people come to his place, they're not sitting in some lobby drinking bad coffee and reading Highlights magazine for children. It's a real home. It catches them off-guard. So immediately, that's doing some work for us.

Third Screen: What did you say to kick off the interviews?

Mitchell: I said 'We just want to take this look at black life, and talk about your life, and get you on camera.' It was a risky thing so we began with people we thought we could ask. We just got out our rolodexes, called people we know, brought them over to Timothy's house and said let's just try it out and see how it goes. I did interviews the way I normally do, but I knew from the outset I couldn't be in this thing -- the guy on camera nodding, the shuffling of the file folders with blue cards. So it's people speaking directly to the camera. Each one is a discrete vignette that has its own life. People will say that nobody will sit for a series of talking heads. Yes they will. I wasn't daunted for a second by having a series of talking heads. It depends on who you've got talking.

Third Screen: How did you and Timothy develop the style of the film?

Mitchell: Timothy's style as a photographer is pure and refined at this point. He's been doing it for thirty years. The project is about what both of us could bring to the party. It started with Slash. At one film festival, the audience was saying why is Slash in it? I thought this was about black people. They didn't know that Slash is bi-racial. Then we started thinking of more really cool African-American names and said 'Let's go from there.' I've always hated the phrase 'The Blacklist.' It's a way to reclaim this phrase and make it a list people want to be on. That's how we got the title.

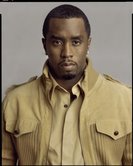

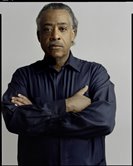

Third Screen: You feature 23 highly diverse people. former Planned Parenthood president Faye Wattleton, former Secretary of State Colin Powell, authors Toni Morrison and Zane, choreographer Bill T. Jones, attorney Vernon Jordan, actors Lou Gossett, Jr. and Keenen Ivory Wayans, musicians Slash and Sean Combs, playwright Suzan-Lori Parks, political strategist Susan Rice . When did you know it was going to work?

Mitchell: The documentary is an opportunity for them to share a sense of themselves in their field of endeavor, to share the virtue of self-knowledge. It's not just my point of view and my questions. It's a lot of different questions. I didn't want to do that thing where there's a fake conversation. There are moments when people take a second to collect themselves. There's a beat and you hear their voice change and then they start talking about something else, something unexpected. These are the moments I prize. Serena Williams told me she is still not taken seriously as a thinker and a strategist. Abdul Kareen-Jabar talks about how he majored in journalism and has written several books. There's the image of a hand to a chin or a furrow on the brow, then their reflections of what they're going through. It's history as a living thing. They are building the blocks of their own history. A few years from now, things will be different. And the documentary won't have the same currency. But documentaries are not timeless. They are timely. It has a point of impact now.

Third Screen: You animate the portraits?

Mitchell: Yes. What are those people thinking? What would they be saying if they were talking? If we do a volume two, people will come prepared in a way that they're not in this one. I just keep thinking about how this time, in each interview, I got caught off guard. I'm not exaggerating about this. That was my hope, that I'd just be drawn into each of these stories. I was extremely fortunate.

Third Screen: What was it like to be the journalist?

Mitchell: You find a way for people to say the things they don't often say. When you see Chris Rock, he doesn't sound like Chris Rock. You get a play of thought and people on camera. For Sharpton, who's spoken to everyone, I thought 'No one ever talks to him about religion.' That was my approach. And he responded. It's a very different look at him. Colin Powell didn't know who I was, and I just tried to make it as immersive an experience as possible for him. Black history is so often put into a few boxes. There's a fatigue about it. People want that to be over. There's a kind of impatience. I know too many people who are successful and who don't lead lives like the ones you see most often in the media about black life. There's a responsiveness to the film because it speaks to us by offering a kind of exhibition of black life that we don't often see. We just played closing night at the American Black Film Festival, and there was applause for every photo. People just went nuts. They were closing the bar, turning off the lights, and people just didn't want to leave.

Third Screen: How do you account for it?

Mitchell: What used to be in the underground now quickly gets absorbed into the culture. Which is good. But so much of it is flattened and boiled down. Documentaries have become circumscribed because there are so many channels around. Even independent films and alternative music now have their own marketing rubrics. But documentaries still have an emotional weight. I just got back from a screening in Detroit, my hometown, and it was a complete gas. The greatest thing. If you'd said to me two years ago that I'd be chasing aorund the country doing interviews and promoting a documentary, I'd still be laughing at you now.

Third Screen: And if you were to be one of your featured film vignettes. What would you say?

Mitchell: Just another black man looking for a job.