Art. It doesn't stop wars. It doesn't cure disease. It doesn't pay down the deficit. And isn't it effort enough to simply get through each day out there in the big unframed world?

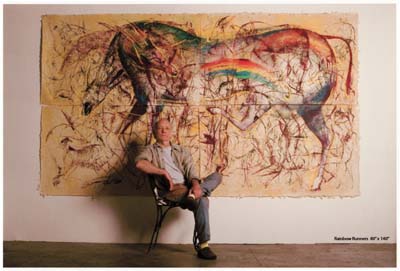

A painter and illustrator with an armload of books, the subject of a documentary film now available on YouTube called Arisman Facing the Audience, chair of the graduate division of the School of Visual Arts in New York City, and an exceptionally congenial person full of wonderful stories and thoughtful responses to impossible questions, Marshall Arisman's new work includes an illustrated novel called The Divine Elvis and a children's book, The Cat Who Invented Bebop, just out from Creative Editions (www.thecreativecompany.us). The Cat Who Invented Bebop is the story of a fabulous feline who plays one song with his front paws and a second song with his back paws. (There is a jazz legend, Arisman tells me, that Charlie Parker played two songs at the same time in his solos.)

Arisman is seriously not "art light." His portfolio includes graphic illustration and covers on important issues of the day for Harper's, the Nation, Time, U.S. News and World Report, the New York Times Book Review. His subject matter does not shy away from our most primitive impulses and behaviors. He is at the very heart of the question asked of much contemporary art -- why does it have to be so dark, so graphic, so violent?

Years ago, he was invited to do a painting for Playboy to accompany their publication of Norman Mailer's book, The Executioner's Song, which was based on the execution of Gary Gilmore. "How much blood do you see in your mind's eye?" Arisman asked the editor before painting it. "About two pints," the editor replied. The painting never ran. Hugh Hefner decided it was too violent and brought back the "Playmate of the Month" put on hold for that issue instead -- the Christmas issue.

Third Screen: What is the thing you wish people understood about how to look at art?

Arisman: That it can clarify vague memories or impressions that exist within. We have all looked at thousands of paintings. Regardless of the artist's intent, the lingering pictures that hang on the walls of my brain are the ones that remind me of something I already know.

Third Screen: When you look at art, what happens? Let's take that famous series of paintings by Rothko -- the ones he did for the Four Seasons restaurant in New York and then wanted to remove because he didn't like the way people were responding to them. If you were eating a steak, and you looked up to see those Rothko's, how would it go?

Arisman: Mark Rothko, one of the greatest artists of the 20th century, cared intensely about society and worried whether the world would last another decade. Around the time of his suicide in 1970, I was in the Army Reserves, attending weekly meetings. A fellow reservist was the New York City cop who found Mark Rothko's body. "Only old guys do that," he said. "Tape their fingers with Band-Aids before cutting their wrists with a double-edged razor blade." Rothko regarded his abstract paintings as presences. Similar to human presences. He wanted them treated with love and reciprocity. In 1947, he said "A picture lives by companionship, expanding and quickening in the eyes of the sensitive observer. It dies by the same token." I asked the cop if he had looked at Rothko's paintings. "I spent some time in his studio looking at those ugly brown squares on canvas," he said. "You're the artist. Tell me why anyone in their right mind would pay thousands of dollars for them?" No doubt Rothko had observed the cop or someone like him eating in the restaurant where his paintings hung.

Third Screen: Who influences you? What do they offer you?

Arisman: In 1968, I saw my first Francis Bacon exhibition at the Guggenheim Museum. Starting at the top, wandering down the spiral walkway, I could feel those paintings enter my body through my nerve endings. When I reached the main floor I understood that contemporary paintings are an experience of emotions that enter the spectator on more than one level. Like a writer telling more than one story at a time, Bacon confirmed my own belief that figuration does not have to be one story, one narrative.

Third Screen: And some of those stories are necessarily harsh?

Arisman: We live in a violent world. That is a fact. As an illustrator, I am asked to visualize the horror of real events and real people. As a painter, I ask myself to create pictures that I don't fully understand. Pop Art dominated the American art scene in the sixties. Figuration had moved from an emotional base to a conceptual one. Roy Lichtenstein was referencing strip cartoons and advertisements of every-day objects -- a foot on a wastebasket, a hand holding a sponge. Warhol was silk-screening movie stars and soup cans. Rauschenberg was combining disparate objects. I was told by gallery owners that my work was too emotional.

Third Screen: Is this what the documentary about you tried to consider?

Arisman: Tony Silver, the director of Style Wars, called and asked me to be the subject of his next documentary, a film called Arisman Facing the Audience. I argued that although I was a far cry from being a household name. Tony argued that the documentary might unveil why a nice guy like me makes so many pictures about killing. I argued that my mother had already asked that question. Tony argued that my mother was not a filmmaker.

Third Screen: What was your mother like?

Arisman: My mother had the calloused hands of a longshoreman. At the beginning of each day, she rubbed copious amounts of Vaseline into her chafed and cracked skin. She plowed. She planted and harvested the garden. She canned and jarred organic vegetables and rolled her own cigarettes. She drank gallons of coffee and bit her fingernails down to the quick. She was also an artist. She was always making something from found materials -- wood, cardboard, paper, string, yarn, usually an animal sculpture. Later in life, when arthritis bent her fingers, she began shaping animals out of papier-mache and bread dough. Her sheep, made with furry coats out of scraps of an old white winter jacket, had leather ears and big eyes. Her sheep were folk art masterpieces. I arranged to have them seen by my friend, Ray, who was the director of the Smithsonian Folk Art Museum. He loved them and she was paid to make twenty sheep for the gift shop. They sold out in a week. Ray ordered one hundred more. Pleased that I had promoted additional income for Mom and generous praise for her artistry, I called her, expecting thanks. "Never, and I mean never," she screamed into the phone, "interfere with my life again. I hate sheep. I never want to make one again." And she never did. Nor did she ever make anything else again, either. I have the distinction of being the artist who killed the creative instinct in his own mother.

Third Screen: How should we regard violence in paintings?

Arisman: Horrific events captured in a photograph are not the same as when an artist paints them. This has something to do with how we perceive time. The photograph represents a split second. The paintings takes longer to complete. We look at photographs, not the photographer. We look at a painting and wonder why someone painted it.

Third Screen: Do you find it ironic that we easily accept so much violence in television, but not in art?

Arisman: In 1984, Time magazine commissioned me to paint a cover that would visualize the death penalty. My intent in painting was to paint an image so horrific that it would evoke an audible scream on the news stand. I took the painting to the Time/Life Building. Carefully unwrapping it, I showed it to the Art Director who carried it into the editor's office. The editor emerged from his office carrying the painting and said "I'm sorry. We're not going to use it. It's too violent."

Third Screen: What interests you most at the moment?

Arisman: For the past two centuries, although generally disregarded today, art has reflected how we see ourselves mentally, physically, and spiritually. These days, when asked at dinner parties in New York what kind of paintings I do, I hesitate knowing that somehow God will slip into the conversation and I will never be asked back.

Third Screen: How do you address art in global terms? In 1999, you were the first American artist invited to exhibit at the Guan Dong Museum of Contemporary Art in Guangzhou, China. What did you show them?

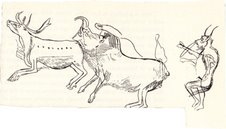

Arisman: A series of drawings, paintings and sculpture of sacred monkeys. I believe, as the Native Americans believed, that certain animals are sacred and carry knowledge. I have painted buffalos (Native American), cats (Middle East), and monkeys (Asia). At the opening of the exhibition, an 80-year-old Chinese artists, famous for his political drawings, slapped me on the back and said, "You, an American, have come to China with traditional Chinese subject matter (the monkey) at a time when all Chinese artists are throwing out tradition. You have just slapped all Chinese artists in the face and I love you for it."