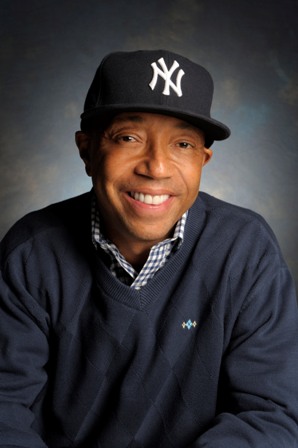

A lot of people think of rappers and hip-hop artists and performance poets and urban youth in general as angry. But an interesting turn of events is occurring in America. These days, they actually seem calm and well-adjusted compared to the rest of us, as we watch our safe vision of our savings and jobs and hopes do cartwheels down a winding path. There's never been a better time to learn and listen from American business leadership that understands what it means to be an outsider, and to bring the outsider mainstream. So I had a chat with media mogul Russell Simmons, master of helping American youth channel their anger and frustration into art, advocacy, and entrepreneurship -- individually, in their communities, and as members of the next generation of leadership in this country. I asked him what he's up to these days, and what he thinks about when he sees the free-floating anxiety and disenfranchisement in America that used to be reserved for the under-served.

Simmons: "I know a lot of angry liberals right now. Hell, I know a lot of angry vegans.

Third Screen: You've launched an extraordinary roster of careers -- Def Jam back around 1989 brought us Chris Tucker, Jamie Foxx, Bernie Mac, Cedric the Entertainer, Dave Chappell, Martin Lawrence, DL Hughley, and I'm not even listing the Hip-hop stars of your Def Jam music label. How do you recognize that talent, and where do you see it now?

Simmons: I didn't do it alone. I had talented partners. Stan Latham for one. Talent scouts. I'm always surrounded by smart talented people.

Third Screen: What do you look for in the people?

Simmons: I look for people who have insight in places where I don't. Who is the best in their community? Who is the best developing artist? These are people who have already created a space for themselves. Guys like Jamie Foxx were on the verge, were ready to go, so we just gave them exposure. And they became urgent. They were already hot. I just gave them some gas for the fire.

Third Screen: What made you say to yourself let's get some poets on major cable? Now you're on HBO again with Russell Simmons Presents Brave New Voices . You not only brought poets to most television screens in America, you did it twice.

Simmons: I just said let's get some poets on tv. And when they said that sounded unlikely, I made it worse. I said, no man, I want to put a bunch of black poets on stage, too. Some Latino poets who barely speak English and Asian poets who can't believe how discriminated against they are. It was luck nad being in the right place. I wasn't saying nothing somebody else wasn't saying but they wouldn't hear it from them.

Third Screen: And you took Def Jam to Broadway in the '90s? Live poetry on Broadway?

Simmons: We got a Tony. Look at it this way, black actors on the road, flying around the country working as poets. Those people are inspirations for millions of kids who write. We have great ratings. It was an interesting art form you couldn't see anywhere else on television. Imagine that! Poetry!

Third Screen: It's not Emily Dickinson in The Belle of Amherst. Do you think music and rap make the difference?

Simmons: No. Music is the noise that surrounds the stillness of the art form. You're operating from a space that's really inside. The poets who do this are uniquely conscious of this silence, this stillness.

Third Screen: And when to break it?

Simmons: The soundtrack in the poetry is the soundtrack from your own heartbeat. They take it from there. They look inside. If they see anger, they talk about that.

Third Screen: In your first book, Life and Def, you wrote ""I believe hip-hop is an attitude." It can be "non-verbal as well as eloquent. It communicates aspiration and frustration, community and aggression, creativity and street reality, style and substance." In your second book, "Do You! ((as in play yourself rather than doing impressions of anyone else) you call the sensibility you've brought to art and commerce in America "Images represent[ing] our American Dream." You meant the images of the disenfranchised, but those images have gone mainstream. How would you define mainstream America now?

Simmons: There's a lot of fear out there right now, and it's not just an urban thing or a street thing. Suffering will always be there. You'll always have the poor. You have to own your own progress. It is true that because of the economy and the fear factor the president is able to execute a lot of promises that it would be difficult to deliver it not for the fear factor. It's funny. He's delivering on what he promised and we call it fear. George Bush also delivered on what he promised and called it fear. Some of the stuff Bush did he did because we allowed it. We were fearful. Same thing is happening now to help the Democrats deliver. But I feel the choices our president is making now are safer and better.

Third Screen: You see a climate of inclusion? Even in this economy?

Simmons: You know in general, the most aggressive views governing this country speak a lot about inclusion. We still have some people in this country who don't really get that we all have the same agenda, aspirations, hopes, and fears. I want people to be free and to be able to express themselves, to find the best ways to say things so that people can digest them. We need to hear everyone. We need dialogue between police and the community. They're angry. They're hurt. A dialogue can cause a shift in consciousness in the person if he's understanding you and listening. This morning, I was in Corona, Queens, at a signing ceremony of the Rockefeller Drug Law reforms, with Governor Patterson and Senate Majority Leader Malcolm Smith and Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver. Charles Rangel was there. Assemblyman Jeffrion Aubry was honored for the decades of work he's put into getting those harsh laws repealed and re-written. It took place at the Elmcor Community Center, where Aubry worked many years ago and first saw the havoc caused by those Rockefeller Laws.

Third Screen: The original laws, written by then-Governor Nelson Rockefeller, were an attempt to come down hard on the crack epidemic of the 70s?

Simmons: Today's ceremony was a good scene. It sets the stage for a shift in the national laws. I grew up in Hollis. It was the drug capital of Queens back then. Whole families destroyed. Now there's a shift, some good seeds have been planted, and it gives us an opportunity to bring things up to date. I've been talking to people in Washington. We need advocates who are going to create awareness. We now have politically efficient, researched, and properly supported systems in place.

Third Screen: The rappers were part of the advocacy?

Simmons: We had our rallies and our Hip-hop summits on this and other issues of importance to today's youth. I was speaking recently on a panel about yoga and spirituality and what we need to do in this country, and an eighteen-year-old kid got up and said "what about your jeans business?" He's right. I had too many businesses that are frivolous. I have enough. What interests me most is under-served communities. We need a new style of empowering these people, and new approaches.

Third Screen: USA Today recently named you one of the "Top 25 Most Influential people of the Past 25 Years," calling you a Hip-hop pioneer who is re-shaping the face of modern philanthropy. Elsewhere, you've been described as a media mogul who is "pushing Hip-hop on to new plateaus of power and relevance." In 1995, you founded Rush Philanthropic Arts Foundation with your two brothers. The organization is dedicated to providing disadvantaged urban youth with significant exposure and access to the arts, as well as offering exhibition opportunities to under-represented artists and artists of color. You're the Chairman of Rush Community Affairs and the Foundation for Ethnic Understanding, dedicated to bringing all religions and ethnicities together. The finale of your 45-city poetry slam just happened on Brave New Voices. End of May, it's the launch of a new anthology called The Audacity of Post-Racism online at your Internet site, www.globalgrind. com, where people 25 and younger are sharing their conversations and essays on race. That's quite a bit. What else?

Simmons: I would like to employ more people but I don't want to empower my charities at the cost of exploiting people or doing things that are not useful, so I'm working on that. These days I've been thinking a lot about gay marriage. I'm a big supporter. Federal gun laws is another one. There are a bunch of battles. I don't like to use the word war, war on drugs, but it's okay. New things to try to change. It's all good.