What is the breaking point that pushes someone to leave their country in order to preserve a chance of survival?

Every day, thousands of people in Syria make the terrifying decision to leave. At some moment on some day, they declare they've had enough. They gather the family, pack just the possessions they'll need for survival into the few bags they'll be able to carry, and embark on a dangerous journey lasting days or weeks, heading toward an uncertain future. They calculate that that future has got to be better than what they face where they are.

Joseph Bednarek, program officer at The Global Fund for Children, talks with kids at a temporary refugee service stop in Serbia.

From the accounts I've heard, they are fleeing extreme violence, personal threats, and repeat exposure to horrific atrocities. And they decide the time has come to bet on a different future in Europe.

I recently witnessed the flow of refugees firsthand. I was in Serbia, where The Global Fund for Children was holding a workshop for grassroots organizations from the United Kingdom, Lebanon, Turkey, and Serbia that are affected by and responding to the refugee crisis.

Over the course of the week, these groups--led by courageous local leaders who are responding to this crisis head-on--discussed the current situation and the ways in which their programs had adapted: a sea change in the ethnicity and origin of the children seeking their services, a doubling and tripling of demand, new program needs, expanded hours and days for services, new funding access and requirements, and new collaborations and partnerships. It is an intense time for them, but they are committed to meeting the needs of these children and families.

At our workshop, a local UN expert shared the facts and figures of this crisis. In 2015, 560,000 refugees from Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan passed through Serbia; 40 percent of them were under the age of 18. Unlike many other refugee crises, this one has a constant--and rapid--flow. Because it is a dynamic migration, no systematic long-term feeding, shelter, education, and health services are in place. Instead, the coordinated refugee response consists of rapid assessments, the meeting of immediate needs, and the provision of information for an onward journey, so much of which remains unknown.

Yet even after learning the context and data from our grassroots partners and the UN representative, I was not prepared for the reality I'd witness on our site visit.

On a dreary, damp, and cold winter morning, we took a field trip to the town of Sid, an important railway transit point in Serbia from which people cross the border into the European Union. Once there, they press onward toward Germany, Austria, and other European destinations. The massive numbers of refugees had overwhelmed the town, so the Serbian government and UN authorities had set up a waiting and service point at a highway rest stop and roadside motel a few miles away from the town and railway station.

Each train leaving from Sid typically takes about 1,000 refugees, and approximately 40 buses were lined up at this roadside rest station to wait for the announcement that a train was ready to board and depart. For a refugee, the wait could be a few hours or a bit more than a day, depending on the order of arrival and the next scheduled trains.

Staff members from the Asylum Protection Center, a grassroots organization based in Belgrade, play games with young refugees.

The rest stop had been transformed to a temporary refugee layover service point. A dozen NGOs, along with UN and government authorities, tried to make order from chaos and convey a sense of safety, comfort, and security, while helping refugees make preparations for the rest of their journey. A large heated tent offered warmth, shelter, soup, and bread. A row of portable toilets provided basic sanitation, so the indoor toilets of the rest stop were not overrun.

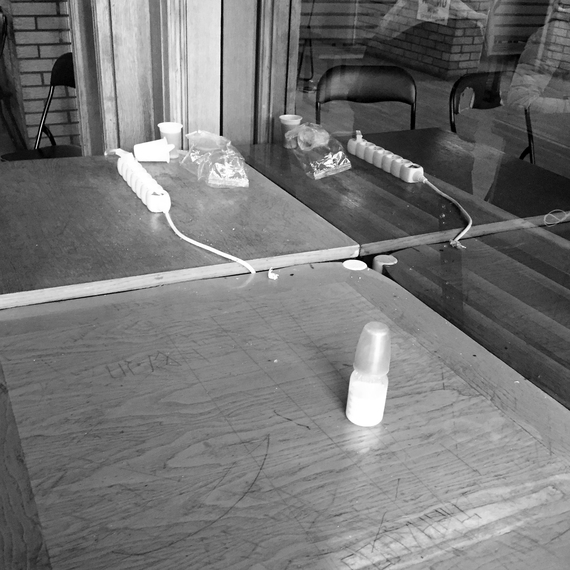

Another basic need for these refugees is Internet access. A row of chargers extending from the side of a van equipped with WiFi provided refugees with a 21st-century lifeline to those left behind in their home country and to those they hoped to find in their future destinations. Basic medical services were available from an international NGO. A small play area was supervised by childcare providers from NGOs, and a makeshift private changing area for women had been created in the rest stop dining room.

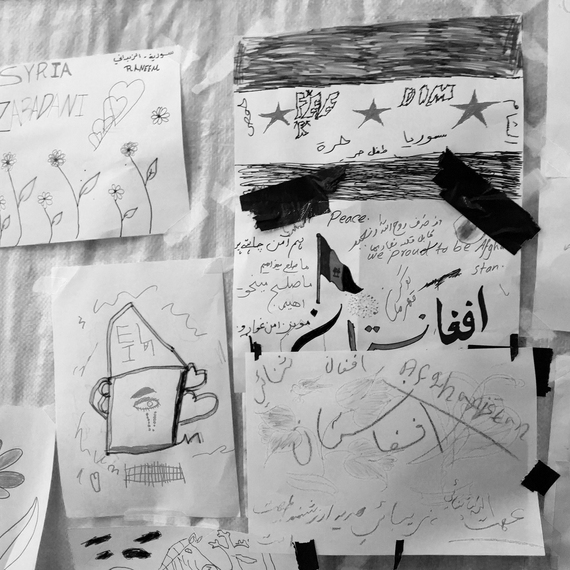

As I took note of my surroundings, I smiled--and winced--at the children's drawings posted on the tent's tarp walls. There were mostly pictures of crowded boats, although one declared Michael Jackson the King of Pop.

My colleague Rana, representing our Lebanese grassroots partner Tahaddi, spoke Arabic to a young boy of about 8 years old, and translated his responses to me. "I come from Syria," he began. "My family was on a big boat, and then a small boat." His eyes as big as saucers, he told her, "I was scared on the smaller boat because they told us not to move or we would fall off."

The Asylum Protection Center, a Global Fund for Children grassroots partner based in Belgrade, Serbia, was leading games for the children in the tent. The children smiled and laughed as they played charades, which served as a welcome distraction from the stresses of the trip and gave them the freedom to be a child again, even if only for a short time.

I watched a mother sitting on a nearby bench, a distant and tired look on her face. Although I imagine that having her children safe and entertained provided some measure of temporary respite for her, her expression remained worried. Since the refugee crisis began, the Asylum Protection Center has opened a 24-hour, seven-day-a-week center to assist with the psychosocial and legal counseling needs of refugee families.

Another Global Fund for Children partner based in Belgrade, NGO Atina, also does work at the refugee rest stop. The staff we met wore big badges that said, "I'm here to help," in multiple languages, from Serbian to English, Farsi to Arabic. Atina staff was approached by many refugees looking for assistance and information--knowledge is power on this journey.

Suddenly, as we were walking through the lobby of a former roadside hotel situated at the rest stop, a border authority appeared and clapped his hands. "Bus. Bus." He clapped again. "Bus." Word had arrived that the train would be boarding in Sid, and people had to make their way to their bus to leave.

While it wasn't chaos, there was a definite sense of urgency. There was little time to board the buses, perhaps ten minutes--or else be left behind. People gathered their belongings, their cups of water, their children, and streamed to the door.

At this moment, I became aware of a stressful situation in a children's play area. A mother had gone to pick up her child to board the bus, and he wasn't there. Her face paled, and I sensed her rising sense of panic. I suddenly understood how quickly and easily a child could become unaccompanied or separated from family, with each parent or older sibling thinking the child was with another family member. Fortunately, it was a short moment before the child was located, and mother and son headed toward the buses.

The rest stop was cleared in a matter of minutes. It had gone from several hundred refugees to a few dozen NGO workers. It was quiet and calm. But soon the next bus would arrive and start the queue for another train.

In the now quiet and empty room, I noticed a baby's bottle, half full of milk, sitting on a table. It had been left behind. A mother had probably left it there in her haste to gather her belongings and her baby. My heart ached. She'd need it in a few hours, I thought. And I bet she had only packed one.