As someone who grew up with the first and second generations of nature programming in American television, I am a fan of documentaries on wildlife and other animals. Movies like March of the Penguins, Winged Migration, and the recently released Oceans are among my all-time favorites.

A few months ago, Ted Williams, a brilliant columnist with Audubon magazine, wrote a devastating critique of nature fakery in wildlife photography. I confess that I have long viewed certain footage or photographs and wondered to myself, "How did they get that shot?" It seems so hard to get a glimpse of these animals. It seems all but impossible to get this extraordinary, extended footage or these perfect photographs.

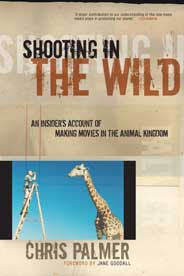

Still, I see wildlife film programs as a powerful force for good, and so does Chris Palmer, author of Shooting in the Wild: An Insider's Account of Making Movies in the Animal Kingdom.

Still, I see wildlife film programs as a powerful force for good, and so does Chris Palmer, author of Shooting in the Wild: An Insider's Account of Making Movies in the Animal Kingdom.

Palmer's new book is a sharp and searching assessment of the contemporary wildlife media universe from someone who loves the field and wants to see it live up to its promise. It's a passionate plea for whole-hearted conservation from someone who has produced some of the strongest pro-wildlife programming there is. And it's chock-full of good ideas for addressing the ethical problems that arise in wildlife filmmaking.

Shooting in the Wild offers a great short history of the wildlife film genre, from the earliest efforts to the current IMAX blockbusters. A 30-year veteran of nature programming, Palmer presents a true insider's view of what goes on behind the camera, and the challenges of funding, conceptualization, and working with scientists and other experts.

To his credit, though, Palmer doesn't gloss over the difficult subjects; he takes them on, fairly and squarely. His treatment of the deaths of Steve Irwin and Timothy Treadwell, for example, are part of a broader discussion of disturbing trends within the wildlife film industry--trends that involve sensationalism, unacceptable risk-taking, staging of scenes that deceive audiences, and, on occasion, animal abuse.

One of Palmer's most serious concerns is that the popularity of wildlife programming has resulted in the entry of less scrupulous filmmakers into the field, people who are more ready to take advantage of animals for profit. He is especially tough on the so-called "nature porn" and "fang TV" genres, and the recklessness that some filmmakers and on-camera personalities have demonstrated in their quest for "money shots."

Palmer's exposé of the industry's less appealing elements reveals a darker side in which directors use and abuse captive animals to get them to do what they want, when they want it. An increasing number of filmmakers, he argues, are producing films that focus on the most sensational elements of animal behavior--hunting, killing, or being killed--because that is what sells.

Palmer is also concerned about the prevalence of game farms as sources of supply to the industry, and disturbed by the lack of standards and the lack of initiative on the part of filmmakers to reform the sector.

Given his alarming portrait of the recent adulteration of wildlife programming, I was pleased to see Palmer's wonderful vignettes of people who are doing things right in wildlife filmmaking. Palmer singled out The Humane Society of the United States' own Kathy Milani for her work on short-format, small-budget films that have advanced our campaigns, and it's well-deserved praise. For more than 15 years, Kathy has been a pioneer in our efforts to make visual media central to our campaigns and public education work, whether it occurs via humanesociety.org or other avenues.

Shooting in the Wild contains many original ideas about the future of wildlife films as a means for educating the public and shaping popular attitude and opinion, and on the challenges of contemporary technologies like computer-generated imagery. But its real strength lies in Palmer's attempt to articulate a morality of wildlife filmmaking, his recommendations for more skillful, responsible filmmaking, and his thoughts concerning better training, guiding principles and the concept of an ethics ranking system for the industry.

Media has a tremendous influence over the way we humans view the natural world, and wildlife films are essential to the conservation and preservation of wild animals. Palmer's book gives me hope about the future of such films, and I'm delighted with the result of his efforts to distill the lessons of a lifetime's commitment to raising people's awareness about animals in the wild.

This post originally appeared on Pacelle's blog, A Humane Nation.