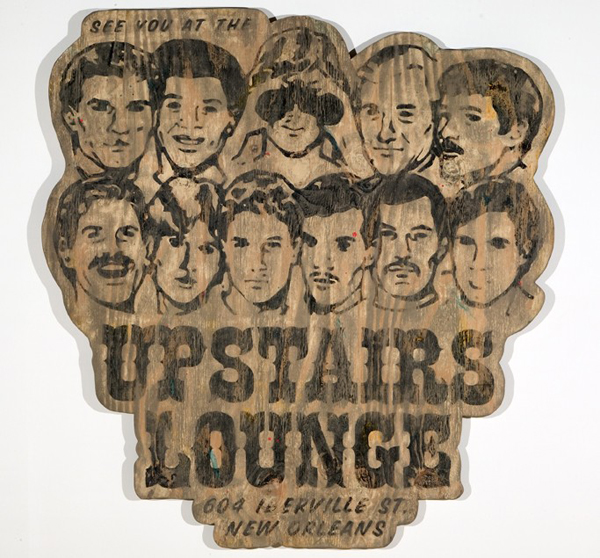

Image copyright Skylar Fein 2013

The tragic nightclub fire in Santa Maria, Brazil, this past weekend is one in a long, painful series of such incidents. As of this writing, 235 people are known to have lost their lives in the fire, and it will certainly be remembered as one of the deadliest nightclub fires in history. We mourn the loss of lives and pray for the Santa Maria community.

In June 1973 an arson attack destroyed the UpStairs Lounge in New Orleans, killing 32 of its predominately gay male patrons. Despite its grim status as the most fatal crime against LGBT people in U.S. history, the event remains obscure, its victims largely unknown and unremembered. Their stories were forgotten years ago by an uncaring media, an uncomfortable church parish, a city whose economic imperative is to protect its reputation and a cowed gay community that wants to avoid a fight. No one was ever convicted of the crime.

As we close in on the 40th anniversary of the fire, two new works appearing this year will endeavor to break the decades-long silence surrounding this act of unspeakable violence, bringing new light to the tragedy and a new voice to its victims: my own new musical play Upstairs, and Clayton Delery's forthcoming book Nineteen Minutes of Hell, a history of the fire and its aftermath, on which much of my play is based.

In this conversation Delery and I discuss violence against LGBT people, the South's history of silence on LGBT issues and the reasons that the UpStairs fire still matters today.

Wayne Self: Most of the relatively short histories one reads about the fire today focus on the aftermath, and the silence, indifference and even ridicule that followed the tragedy. Why do you think that is?

Clayton Delery: There were no proclamations of outrage or sadness from politicians at any level. There were no arrests. There'd have been no memorial service if the Metropolitan Community Church, a primarily LGBT Christian denomination whose New Orleans church counted many of its members among the dead, hadn't sent their founder, Troy Perry, into town to organize one. Troy Perry and the other clergy and activists had a difficult time even finding a location for a service. When they asked for cooperation, they were turned down by clergy and leadership from the Catholic, Episcopal, Baptist and Lutheran churches. Only one Unitarian congregation and one unusually liberal Methodist congregation were willing to cooperate. In the end, they went with the Methodist church, because it was in the French Quarter and close to the scene of the fire.

Self: The spirit of the Stonewall riots, which had happened only four years earlier, almost to the day, had not yet come to New Orleans, where some LGBT leaders (who, let's admit, were mostly the "G" part of that acronym at that time) joined political and religious leaders in a conspiracy of silence around the fire. We are both Southerners. Do you find that the South was slower to embrace the "coming-out" movement? If so, why?

Delery: In a way, the whole city was staying in the closet about the fire. This arrangement protected tourism for the city, protected religious leaders from having to choose between compassion or condemnation and protected New Orleans' gay community from "coming out" of the quiet arrangement they had with the NOPD and entering a political and legal fight for equality that they didn't think they could win. Many people were comfortable with homosexuality being thought of as simply another vice in a city known for profiting from vice in myriad ways.

Self: Of course, today we still find lots of very good reasons to stay in the closet. I don't just mean the celebrities and other notables who don't come out but our refusal as a community to discuss our own problems with the larger society. Drugs. Health concerns. Our own racism and internalized homophobia. We still keep quiet about these things.

Delery: And, in some other countries, of course, the closet is still very much in effect, sometimes with good reason.

Self: We tend to think of history as moving toward progress, but that's just not the case. It moves in fits and starts. It's easy to get comfortable.

Delery: In New Orleans at that time, things on the surface weren't as bad as they had been in New York in 1969. It had been several years since there had been a mass raid of a bar or a gathering place. Gay people lived in relative peace. So, in some ways, people were comfortable. There was no immediate reason for a Stonewall-type event. But the fire revealed a deep current of homophobia.

Self: Did things change after the fire?

Self: Did things change after the fire?

Delery: Some people say it was a galvanizing moment for the community, and some say that it was completely ignored. The truth, I think, lies somewhere in the middle. It did reveal a need for a more organized, more vocal, community, but the New Orleans response was never going to be like a New York response. It was quieter and more in line with New Orleans sensibilities.

Self: Why do you think the fire still matters today? Is it a cautionary tale? Is there anything inspiring or motivating in the tragedy?

Delery: I think there is inspiration to find in the tragedy. Some of the stories of the night of the fire are so heroic and profound. So many responses are compassionate and brave. Seeing these victims as individuals, I think, reveals a great deal to respect, admire and be inspired by.

Self: I think every victim of violence should matter. It's an error to fail to honor the victims at the UpStairs Lounge while we honor so many others. What we choose to remember, what moves us to action, says something about ourselves. Do we want it said, for example, that the hundreds dead each year from urban handgun violence mattered less than the suburban children killed at Sandy Hook? Or that the soldiers who died in Afghanistan mattered less than the soldiers who died in Iraq? Of course not. The same is true here. It's right that we honor Matthew Shepard, for example, but some of the victims here were no less young, no less active, no less wonderful.

Delery: I also think it matters because of its place in context. The UpStairs Lounge was a known meeting place for the Metropolitan Community Churches, and the leaders of that organization saw it as another in a series of fires at their churches. There was a great deal of concern at the time that the fires were part of a conspiracy, or at least a trend.

Self: That's certainly relevant today. We deal with domestic bombings and shootings and other acts of mass murder on a more frequent basis. There's no conspiracy, but it sometimes seems worse than a conspiracy. There's the sense that something bubbles up from our primordial soup. Something swells in the zeitgeist that provokes these men to what they think is revolutionary zeal or psychic self-defense or protection of some perceived birthright, or a primal scream at a perceived cosmic injustice.

Delery: No arrest was ever made, but there was a suspect who died before he was arrested. If he was indeed the arsonist, and if the suppositions we can make about his motives are correct, then a straight line can be drawn from his act of violence to the mass gun violence we see today: angry young men with severe depression who, for some reason, come to feel terribly slighted by life, or by their communities, or both. In this case it may have been homophobia, but homophobia turned on oneself.

Self: I wonder if what we call homophobia is really "femophobia," some fear of losing one's manhood or being thought of -- or thinking of oneself -- as a woman, as not masculine enough, as a failure as a man. Certainly that would have been in play for the suspect.

We continue to grapple with violence, with why men (and it always seems to be men) turn into mass killers. The history of the UpStairs lounge provides few answers, but it does remind us that the history of mass violence in the U.S. is not a short one. It gives us an opportunity to reflect on what messages we send to our young men and boys as we raise them.

* * * * *

Workshop performances of Wayne Self's Upstairs will be staged Feb. 12 to 14 in the Bay Area in preparation for a June premiere. To attend one of the productions or learn more about Upstairs, click here.

An effort is underway to help bring the production to New Orleans in time for the 40th anniversary of the fire. To learn more about this effort, click here.

Clayton Delery's book is currently soliciting publishers.