Over the past 50 years, humans have put an enormous amount of pressure on coral reef environments by altering their waters and tearing up their foundations. From dynamite fishing to global warming, we are rapidly sending the world's reefs into oblivion. The latest reports state that as much as 27 percent of monitored reef formations have been lost and as much as 32 percent are at risk of being lost within the next 32 years. -- Earth Observatory, NASA, 2015

"The Earth is a unique system in the universe, the only planet we know of that's hospitable for humankind. And that's because we have oceans." -- Dr. Sylvia A. Earle, Marine Biologist

On a deceptively serene Saturday morning in June, as Hurricane Blanca churns in the Pacific Ocean off the southern Baja Peninsula, Judith Castro Lucero, Director of ACCP (Amigos Para la Conservacion de Cabo Pulmo) and I watch the yacht Maranatha motor into Marina La Paz.

The night before, Castro Lucero and I had driven north ahead of the storm along the Gulf of California from our village of Cabo Pulmo in the Cabo Pulmo National Marine Park to interview Dr. Sylvia A. Earle, oceanographer, marine biologist, National Geographic Explorer-in-Residence and conservationist.

Earle and her guests aboard the Maranatha had planned to sail south to join our community for a screening of her film Mission Blue--in which the reef is featured as a conservation Hope Spot--kicking off a weeklong celebration of the reef's' twentieth anniversary as a protected Marine Park and UNESCO World Heritage site. Instead, they would fly out of La Paz ahead of the storm.

Earle's research, counsel, and advocacy have been crucial to the preservation of the Cabo Pulmo reef--the only hard finger coral reef on the North American continent and home to over 800 species of plant and marine life.

If you've ever found a piece of coral on the beach, you will have noticed its rough surface, remnants of polyps that once swelled to contain a single algae cell. Through the process of photosynthesis, algae feed oxygen and other nutrients to the coral polyp, which returns carbon dioxide and other substances to the algae--a balance that not only sustains the coral and algae but that also nourishes 226 species of fish who feed on the reef. Worldwide, fish feed between 30 and 40 million people per year, but they also provide a livelihood for communities like Cabo Pulmo, they have had to change their infrastructures from overfishing to sustainable fishing and eco-tourism.

In 2009, Earle won the million-dollar TED prize for her pioneering work in documenting the degradation of the world's oceans. From that prize, Mission Blue, a global initiative of the Sylvia Earle Alliance, was born. It is an initiative where more than 100 respected ocean conservation groups and organization--ranging from multinational companies to individual scientific teams--are systematically researching and evaluating the health of the world's oceans.

For Earle, Cabo Pulmo, its community and reef, has become a jewel in the crown of what she calls Hope Spots, areas of marine bio-diversity that have recovered from the brink of extinction.

Coral reefs, the ocean's lungs--pulmo means lung--rely on a delicate balance of sunlight, warmth, salinity, and pH factor, or acidity, to thrive. Reefs are particularly susceptible to fluctuations in ocean temperature, nutrient runoff from fertilizers, and acidification.

Cabo Pulmo was not always Mexico's premiere example of conservation and preservation. By the mid-1980s, the Cabo Pulmo Reef was overfished and polluted with runoff and waste, both animal and human. Local residents were forced to go elsewhere to find work. Worried that they might have to abandon their way of life, the community met with experts, including marine biologist Dr. Oscar Arizpe, who, in 1991, was the first scientist to perform systematic research on the marine animals living in the reef.

Based on Arizpe's findings and those of other scientists, a proposal of renewal integrating social, economic, and environmental components was presented to the Mexican government. On June 15, 1995, then-President Ernesto Zedillo declared the reef a protected natural area, and so began a two-decade effort of preservation that today includes an ongoing effort to preserve the fragile desert ecosystem north of the park.

On this morning in June, Earle and her crew, who had been diving for three days in Magdalena Bay near La Paz, welcomed us onboard the Maranatha and settled us into the boat's lounge.

At 79, Earle, who travels 300 days per year, is indefatigable in her quest to educate individuals, communities, and policymakers about the perilous future of the world's oceans and, by extension, our own future.

"Today is Cabo Pulmo's official anniversary," says Castro Lucero.

"Such a wonderful time of celebration," adds Earle. "The gods and goddesses have even stirred up a storm of celebration."

"Yes, we'll dance with Blanca tonight," smiles a relieved Castro Lucero, who has just learned that Blanca has veered into the Western Pacific and that southern Baja will be spared the brunt of the storm.

Wild River Review: You've just spent the past three days diving. What can you report about the health of the Gulf of California?

Sylvia Earle: I call the Gulf of California a Hope Spot, one of the places that is critical to the health of the ocean, for a very good reason. As compared to the first time that I came to the Gulf in the 1960s there's good news and not such good news.

Some things are better: Whales have begun to recover from a time when they were being taken to near-extinction to produce commercial products. There are far fewer sharks, but the good news is the sharks that were here in the middle of the twentieth century--including whale sharks, hammerhead sharks, reef sharks, and great white sharks--are still here.

Wild River Review: You consider sharks to be as beautiful and important to the ocean ecosystem as whales. Why?

Earle: The value of sharks' lives is now widely understood to be more important than their value as products. And when you have sharks in an area, it's a sign of good health. They're top predators, which means they feed on old, sick, and slower fish, keeping an entire population healthy. Sharks also eat other species that prey on smaller fish, keeping predator populations in check.

But it's not just whales and sharks. We are also beginning to look at all fish--ocean wildlife--with new attitudes and new eyes. That's true here, and one of the reasons that I so love spending time in Cabo Pulmo is that the conservation and education efforts taking place in the community are a source of inspiration and hope, not just nationally but internationally and globally. We need to scale up globally and create more communities like Cabo Pulmo.

Wild River Review: How do we begin to scale up?

Earle: By accepting that the Earth is a unique system in the universe, the only planet we know of that's hospitable for humankind. And that's because we have oceans. As a scientist and ocean explorer, I've spent thousands of hours under water serving as a witness to what humans have done to nature generally, but to the ocean specifically, even though the surface probably looks much the same to people today as it did a thousand years ago.

Hammerhead sharks, once so abundant, are now uncommon. We didn't see one shark of any species in our dives here this week. This was one of the sharkiest places on the planet going back a few decades ago.

Those of us who have been privileged to get beneath the surface over the last half century--even those who have recently entered the sea--have seen the changes taking place. Mostly the changes are not good. But in Cabo Pulmo we are seeing what happens when a community commits to protecting their environment--what happens when we give nature a break. One of the best causes for hope is that nature is resilient. The caution though is that systems and species are not infinitely resilient. The residents of Cabo Pulmo have been living an ongoing experiment beside the reef and it is working.

Wild River Review: Where have the hammerhead sharks gone?

Earle: Globally sharks have been killed for their fins, for their cartilage, for their livers, for their meat. But mostly what has driven some species of sharks to near extinction--including the hammerhead shark--is the new luxury taste for shark fin soup. The people in Mexico, generally speaking, are not consumers of shark fin soup, but they have found a market for fins as has happened elsewhere around the world.

Along the coasts throughout Central America and elsewhere in the world, they have taken sharks for their fins alone, throwing the dying fish back into the ocean. In the last few decades, especially with the rise of a large middle class in China and their desire for shark fin soup, overfishing has decimated the populations of sharks.

Wild River Review: Many people still think the ocean is limitless, that you can't hurt it.

Earle: As recently as fifty years ago, we all thought there was nothing humans could do to harm the ocean. We thought the ocean was too big to fail, that we could dump whatever we wanted to into it and take as many fish as we could catch. The fish would always come back, we thought. But now, we have evidence documenting where the big fish were when I began exploring the ocean more than fifty years ago, and showing where the are, or are not, today.

Ninety percent of the big fish, including the sharks, are gone. And where did they go? We killed them. We ate them. We marketed them for products. Just as we did years ago with whales and with wild birds.

If I were a child of today, I would ask, "What were you thinking? Help us out. Will we still have coral reefs, and kelp forests, and whales? Teach us how to care for them."

Wild River Review: You have worked with various groups to save what remains of the harbor porpoise known as the vaquita. According to a recent study, the vaquita population has dwindled to fewer than fifty remaining in the northern part of the Gulf of California.

Earle: The sad truth is that the children of today may be the last to know these very social, playful creatures who are victims of many things, one of them being gill nets, which strangle them.

When I was a child, there was another marine mammal that is gone from reefs in the Gulf of Mexico and throughout the Caribbean all the way to the Bahamas. And that was the Caribbean monk seal--the last sighting was in 1952 when I was in high school.

Wild River Review: All of them?

Earle: There are two other kinds of monk seals. A few hundred of one species still swim in the Mediterranean and maybe one thousand in the Hawaiian Islands. As a child, I didn't know what they looked like. Didn't know they existed. They were once abundant in Caribbean and Mexican waters as far north as Galveston, Texas. When early explorers came to the Caribbean several hundred years ago, they found monk seals lounging on the beaches of the Yucatan.

Wild River Review: They slaughtered them for what?

Earle: We ate them and other fishermen had the idea that the seals were competing for fish. Of course the seals had no choice about what they ate. Now you see how a species can become extinct. Since the vaquita has no choice, it's going to get tangled in nets if the nets are set to catch shrimp, which is something the vaquita eats. Vaquitas and sharks and whales can't go to the grocery store. They can't have a garden to raise corn and rice and beans.

Wild River Review: I notice something interesting in the way you phrase your sentences. You say "we." I find that compelling in that you're saying we are all implicated.

Earle: Because we are--humankind is implicated. I/we have to look in the mirror first. What are we doing? How can we make a change? It always starts with looking in the mirror. Every individual can. Every individual can make a difference either by proactively doing something positive or by doing nothing. That's a decision, too.

We're all part of the problem if we just go with the flow when we know that we can make a difference. Making different choices about what to eat, or not. About what to protect, or not. Or whether to use our voices, or not. To use our power as artists, or if we have a way with numbers, whatever power we've got to use it to make the world a better place--or not, if you choose not to use that power.

But it's always a "we" and it starts with an "I."

Wild River Review: How are you and your team training people, especially young women, to follow in your footsteps? You're a force of nature, but who is coming next? Who are the people we should watch?

Earle: For me it's not gender specific. It's every one of us. Historically, girls have not been encouraged to be scientists, to be explorers, and there's a social kind of constraint, of course. Having the responsibility, a disproportionate part of the responsibility, for caring for families, caring for children. I know this challenge from firsthand experience because I have three children and four grandsons. And some of the time I have spent as a scientist and as an explorer has meant choosing to not be with my children and grandchildren as much as I might otherwise have done had I not been a scientist, an explorer.

The flip side, though, is that I get to share and engage my grandchildren in opportunities to dive with whales and to use little submarines to travel with me along the ocean floor. It's not the same as always being with them when they need me or when I need them. But they will and have created a different kind of community, one that is diverse and full of compassion and curiosity.

Wild River Review: In your book, Sea Change and in the movie Mission Blue, you praise your mother. In fact, you call her your best friend. She often helped care for your children when you were on research trips. Childcare is a huge issue for young women whose work may require them to leave their families for weeks at a time.

Earle: Sometimes you can take your child or your children with you. I've done that often in order to make it possible for me to go to remote places. But I could truly trust my mom and dad to be there for my children. This gave me the latitude to be able to in good conscience take advantage of some of the opportunities that I could not have taken, had I not felt that security.

The other part of this equation is that we are living longer and healthier lives, so there are more opportunities for grandparents to be engaged. It's a privilege to have another chance with my grandchildren--to be able to give to them in ways that I wasn't able to for my young children. To provide them with the opportunity to participate in a larger vision, one example being the vision of Mission Blue, which we formed in 2009 to campaign to ignite public support for a growing global network of marine protected areas like Cabo Pulmo.

And now we know so much more, so we have more to teach them than when my children were little. We've learned more about the ocean in the last fifty years than in all preceding human history and that pace is rapidly increasing.

We know why the ocean matters. We didn't know before. So we were casual about what we put into ocean. We thought our refuse would just go away. Now we know that there is no such thing as away. And if you like to breathe, you must take care of the ocean. More than half the oxygen that is replenished every day comes from small organisms in the sea. And that's true for the photosynthesis that takes place in sea grass meadows and marshes and mangroves forests, in addition to the trees and plants on land. But 97 percent of water is the ocean that forms clouds that brings rain (and sometimes hurricanes) from sea to land and back to the sea. No ocean, no life. No blue, no green. No ocean, no us.

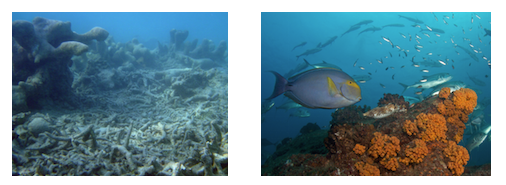

A Dead Coral Reef & A Healthy Coral Reef

Wild River Review: Were she alive, the great biologist Lynn Margulis would agree with you.

Earle: She's been vindicated with what once seemed to be preposterous ideas of the importance microbes play in maintaining healthy ecosystems in people, fish, and, of course, the ecosystems of coral reefs. Now, you can't read a scientific journal that isn't reporting about the crucial nature of microbes in our existence. But at the time Margulis could see what others could not. She was a little bit like the woman in Greek mythology, Cassandra, who could see the future when nobody believed her.

Wild River Review: I thought of her when I read your book Sea Change and watched the film Mission Blue--what you tried to find when you made your deep-sea explorations and how you methodically gathered and presented the evidence that our seas are being degraded.

Earle: I learned from Lynn Margulis. I learned from others who are able to focus in depth on specific aspects of the latest technology or the science behind the acidification of the ocean or the complexity of human relation, whatever it is. That's why I say children of today are the beneficiaries of everything that people have gathered in the past. And you can access it in ways that are unprecedented. Not everybody has a cell phone. Not everyone has access to a computer. But that is rapidly changing so that in most communities, even if there's one computer or somebody learns, that person educates the community, or educates a family--or the country or a world.

But until recently, we thought the Earth would always behave in the same fashion no matter what we did to the trees or the birds or the ocean, air, our water. Scientists at NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) have measured ocean change over the past forty years.

They have hundreds of thousands of ocean water samples showing the changes in pH and temperature. The change to higher acidity, as is currently being recorded, is too rapid for life in the sea to adapt. Still, it's not too late to turn things around. But if all the sharks are gone, and half the coral reefs since I began exploring the ocean are gone--or are in serious decline--how many more years until they're all gone?

Your community in Cabo Pulmo did something brave. You worked together and took action; and when you needed it, you asked for help. That is something everyone can do. We can take positive action. We can show like you have in Cabo Pulmo that nature, even when it's near the brink of extinction, is resilient and can recover.

We lost the chance with monk seals. In the Gulf of California, we still have the chance with the vaquita. We still have the chance with hammerhead sharks. We still have a chance with the resilience of the entire Gulf of California or we could lose it, the way we've lost parts of the Caribbean Sea, if we continue to do what we're doing: generally taking from the ocean for products without limit instead of respecting the greater value of living systems.

Wild River Review: All of this sounds wonderful, but millions of people rely on the ocean for food.

Earle: You're right and I think it's still realistic for people to take some wildlife from the sea. To make one's living from fishing. But to do it with respect. With care. Armed with knowledge that there are some places where we should not take any fish--a protected place. If you leave a reef alone as your community has done, you give the fish and the corals a chance to replenish themselves. This, in turn, gives you a population of fish to catch outside the protected zones.

We can and should pay attention to breeding areas. The feeding areas, the reefs, which are the ocean's nurseries. Those have a heightened value. And if we could focus on maintaining full protection for large areas of the ocean, the resilience is such that the ocean may be able to recover. But we simply cannot take sea creatures at the current rate of commercial industrial extraction. It's not working now and it's not possible to go forward. But to be able to have fish for your families and your communities taken with care and respect--now that makes sense.

Wild River Review: Do you see policies changing worldwide? It took a lot of effort in Cabo Pulmo to protect and preserve the reef, and the community is still fighting large-scale development to the north of us that could destroy the reef's ecosystem with the dredging of harbors and runoff of nitrates from construction of lawns and golf courses in a desert.

Earle: But the great news is the positive effort of numerous scientists and your own community in cataloging the ecosystem of the desert adjacent to the sea and the impact of overdevelopment on it. You have built on your advantage by showing that ocean makes the land more attractive and healthier and the land does the same for the ocean--and that you can even build a successful community that embraces tourism on a sustainable level.

Wild River Review: What advice would you give to those of us who are putting our hearts and souls and time and money into preserving our reef as an example for future communities?

When we wake up some mornings and say, "I can't do this anymore. I just can't take one more piece of bad news about the condition of our oceans?

What do you say to all of us in all our communities?

Earle: Never give up. If not now, when? This is the best chance we'll ever have to turn things around. We're armed with knowledge and also with opportunity. It's not too late. The thing that keeps me going is imagining that if we continue with current policies where will we be in fifty years?

Look at a child and realize that their future is in your hands. It's not just those who will be here fifty years from now. The decisions we make in the next ten years will shape the next 10,000 years.

Wild River Review: But we can't deny the fact that we human beings are greedy consumers.

Earle: Throughout all of human history we have consumed the natural world. All creatures do. Birds do. Fish do. Earthworms do. We consume the natural world as a source of our survival. But no creature has ever consumed at the scale that humans have, and now there are seven billion of us. I think the good news is that a large percentage of those seven billion minds can work to make better decisions. There are a lot of smart creatures out there. Dolphins, elephants, and whales are smart. And there are some really smart birds. I know some really intelligent fish. But they cannot know what humans know and are incapable of inflicting as much damage.

This is truly a pivotal point for humankind. I call it the sweet spot because never before could we know what we know now. Never again will we have the opportunities that exist to make the world suitable for a prosperous, sustainable future.

Wild River Review: Do you think most governments in the world are thinking the way you do?

Earle: Governments have the capacity to look at the evidence. People say, do you believe in climate change? It's like saying do you believe the world is round? Do you believe we're moving around the sun? It's not a matter of believing. It's a matter of looking at the evidence. Any government leader can figure it out.

Twenty years ago, because of action on the local level and pressure on the national level, President Zedillo declared Cabo Pulmo a national marine park. In my dives at Cabo Pulmo, I've seen the abundance of life and diversity as compared to just a few miles down the coast where it is empty of the big grouper, empty of the great schools of jacks, empty of healthy corals and sponges and the other things that make a system prosper. The little things that are critical components of a healthy system are in Cabo Pulmo. You don't have to go very far outside of the protected area of the marine park to see what happens when you fail to take care of the living assets.

Wild River Review: At 79, you are on the road for most of the year and will travel to Washington, DC, after you return to the States. What keeps you going at a pace that would be tough for anyone?

Earle: I'm driven because I know the truth of what I've seen and I know the scientific research. And I want to keep learning. I won't stop because it's the gift of being. If we have our health and curiosity--the wonder that children possess--I believe we have a chance.

To learn more about the Sylvia Earle Alliance and Mission Blue, click here:

Mission-Blue.org

To learn more about the work of the Cabo Pulmo Community, click here:

http://cabopulmoamigos.org

An Extraordinary Hope Spot, is one in a series of pieces about the Cabo Pulmo Coral reef, its community, scientists, both terrestrial and marine; and individuals and organizations within Mexico and around the world who have made and are making the Cabo Pulmo Marine Park one of the world's premiere Hope Spots.

Joy E. Socke is a founder of the online magazine Wild River Review. To learn more about Wild River Review, click here: http://www.wildriverreview.com