The new poll of Cuban Americans in south Florida by the Cuban Research Institute at Florida International University confirms the long term trends in Cuban American opinion that FIU has tracked for the past thirty years. Gradually, but inexorably, Cuban Americans are embracing more moderate views about Cuba, favoring increased engagement over the traditional U.S. policy of hostility. The latest FIU poll also confirms the results of other recent polls, including the Atlantic Council's, which conservatives tried to dismiss as a "push" poll (a poll designed to elicit predetermined answers).

When FIU first began polling Cuban Americans in south Florida in 1991, 87% favored continuation of the U.S. embargo. Today, embargo supporters are a minority at just 48%, and even they don't think the embargo has been effective.

In 1993, 75% of respondents opposed the sale of food to Cuba and 50% opposed the sale of medicine. Today, large majorities (77% and 82% respectively) support both. In 1991, 55% of Cuban Americans in south Florida opposed travel to Cuba. Today, 69% support unrestricted travel for all Americans.

The FIU polls clearly demonstrate that these changes in Cuban American opinion result from demographic changes in the community. Differences in age and experience among successive waves of migrants produced sharply different opinions. Older exiles and those who came in the first waves of migration are the community's most conservative element. Younger migrants and those who have come recently are the most moderate. Recent arrivals are far more likely to favor policies that reduce bilateral tensions and barriers to family linkages, especially the ability to travel and send remittances.

The reasons are not hard to discern. Exiles who arrived in the United States in the 1960s and 1970s came as political refugees, motivated principally by their opposition to the socialist course of the revolution. Often, they lost everything by choosing exile. Recent arrivals, especially those who came in the post-cold war era, are more likely to be economic refugees and far more likely to maintain ties with family on the island. FIU's 2007 poll found that 58% of respondents were sending remittances to Cuba, but fewer than half of those who arrived before 1985 were sending money, whereas three quarters of more recent arrivals were.

Reuniting the Cuban Family

In addition to generational differences, an important reason for the gradual change in opinion has been the deepening ties between Cuban Americans and their families on the island. During the 1960s and early 1970s, it was difficult if not impossible for families to maintain contact across the Florida Strait. Travel to Cuba was prohibited by the U.S. embargo, and the Cuban government would not allow "gusanos" (worms) to return to visit. Direct mail service was cut off, and telephone connections were notorious poor. Moreover, the prevailing opinion in both communities was one of hostility. To Cubans who left, those who stayed behind were communists. To Cubans who stayed behind, those who left were traitors.

The end of the cold war opened new opportunities for the two communities to re-connect. The collapse of European communism plunged Cuba into deep economic crisis. Consumer goods of all types became extremely scarce, unemployment rose, and food shortages appeared because the government could no longer afford to import it. Cuban Americans were moved by the suffering on the island and responded by increasing the flow of both in-kind assistance and cash remittances. As the standard of living in Cuba plunged in the early 1990s, access to dollars became a critical determinant of people's quality of life. Remittances began to climb, from roughly $150-200 million annually in 1990 to $500 million by 1995.

Since President Obama lifted the Bush-era restrictions in April 2009, Cuban-Americans have been able to travel to visit family under a general license and send unlimited remittances. As a result, family visits increased from fewer than 50,000 in 2004 to 600,000 in 2013. Remittances jumped from an estimated $1.4 billion in 2008 to $2.6 billion in 2012. When Cuban Americans in south Florida were polled by FIU in 2011 about Congressman Mario Diaz-Balart's proposed legislation to rollback Obama's policy, thereby curtailing travel and remittances again, opposition was overwhelming: 61% of all respondents were opposed, as were 76% of those who arrived in the United States after 1994.

Do Attitudes Translate into Votes?

Although these attitudinal differences have been clear for some time, until recently, they had not manifested themselves in Cuban American voting behavior. Before the election of moderate Democrat Joe Garcia in 2012, Cuban American constituencies consistently sent conservative Republicans like Ileana Ros-Lehtinen and the Diaz-Balart brothers, Lincoln and Mario, to Congress. Before 2008, Democratic presidential candidates never won more than about a third of Florida's Cuban American voters.

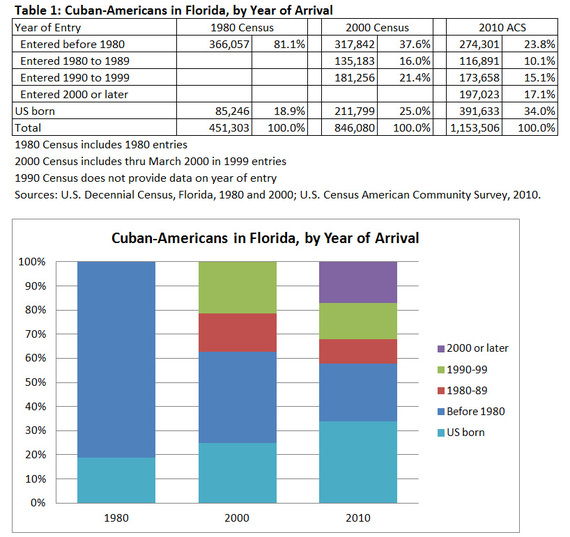

This lag between changing attitudes and voting patterns is also explained by the community's demography. By 2010, those who arrived before the end of the cold war were only 34% of the community, and later arrivals were 32% (Table 1).

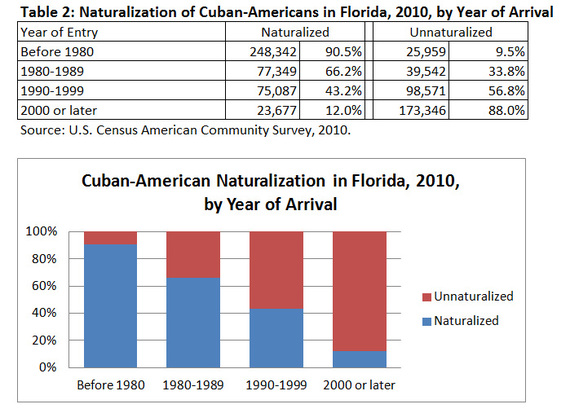

But 90% of the earliest arrivals have obtained U.S. citizenship, as have 66% of those who came in the decade before the end of the cold war. Of those who have come since 1990, only 27% have become citizens (Table 2).

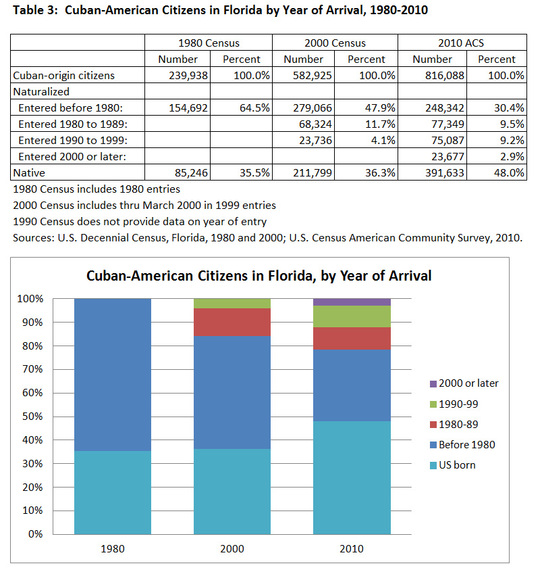

Consequently, the most conservative cohorts of Cuban Americans still comprise a disproportionately large share of the Cuban electorate- 40% in 2010, compared to 12% of post-cold war migrants. (Although, by 2010, the largest share of the electorate was Cuban-Americans born in the United States at 48%: Table 3). As the new 2014 FIU poll shows, registered voters consistently take a harder line on all policy issues than the community as a whole.

Yet even among this more conservative group, majorities now favor greater engagement with Cuba. The cohorts of early exiles are becoming a smaller and smaller proportion of the community as new immigrants arrive every year and as natural mortality takes its toll on the aging exiles. And with the passage of time, more and more of the post-cold war immigrants will obtain citizenship and begin to vote.

As a result, Cuba is not the third rail of Florida politics or presidential politics that it once was. Barack Obama won 35% of the Cuba American vote in 2008 and nearly half of it in 2012 with a moderate policy toward Cuba that Republicans excoriated as appeasement. This realignment of Cuban American attitudes and voting behavior means that the principal domestic political obstacle to a more sensible U.S. policy toward Cuba is disappearing. A bold U.S. president now has an opportunity to establish a legacy no less historic than Nixon's opening to China, and to do so at relatively little political cost.

Coming soon! Back Channel to Cuba: The Hidden History of Negotiations between Washington and Havana by William M. LeoGrande and Peter Kornbluh.

Click to pre-order.