America's aging dams and levees require a new approach to climate-related flooding. (Credit: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers)

Last August nearly 7 trillion gallons of water rained on Louisiana in less than a week, causing the worst natural disaster to strike the United States since Hurricane Sandy. Several levees reportedly were overtopped by the water. Local officials said 60,000 homes were destroyed and damages approached $9 billion. It was the second billion-dollar disaster in Louisiana this year.

Thirteen people died in the flood. One of them was William Mayfield, 68. A witness said she was helping Mayfield through a water-filled ditch when he slipped and went under. He didn't resurface.

This month in Florida, Barbara Dennis died during Hurricane Matthew. As a 70-year-old survivor of breast cancer, she needed a machine to pump oxygen into her lungs. Her electricity went out during the storm and so did her machine. She died in respiratory distress.

In Daytona Beach, Hurricane Matthew led to the death of Jose Barrios. The 9-year-old succumbed to carbon monoxide poisoning in his home while his mother and father were unconscious. Their electricity had gone out, too, and they had put a generator in their house to restore power. It was a fatal decision.

There are many ways to die in weather disasters. During the decade that ended in 2014, fatalities averaged 552 people per year. Last year, 522 people died and more than 2,000 suffered weather-related injuries or illnesses. Thirty-five of the fatalities were children under the age of 10.

These events are exactly the kind of weather disasters that climate scientists predicted. The latest assessment of climate changes in the United States, conducted by more than 300 experts and reviewed by the National Academy of Sciences, reported that precipitation has increased over the last century and downpours have become heavier and more frequent during the last 50 years. From 1958 to 2012, very heavy rainfall events increased 27% in the southeast, the region that includes Louisiana and Florida. They say this pattern will continue.

For more and more Americans, the impacts of global warming are getting very personal and very close to home. And if climate scientists are correct as they have been so far, weather disasters are going to become much more frequent, costly and violent. Temperatures are getting hotter, fire seasons are getting longer, hurricanes are getting stronger and sea levels are rising. For reasons I will explain, we can no longer be confident of protection from the massive investments we made in the past to control rivers and hold back oceans. To put it plainly, we are not prepared for what is happening now, let alone what's to come.

***

Our vulnerability to weather disasters is one of several critical and controversial issues that will confront the next President of the United States. Big national issues range from economic inequality to terrorism, but none threatens us with the long-term uncontrollable consequences of climate change. In this and several subsequent posts, I will argue that the incoming president should use one of the chief executive's most under-rated authorities: the ability to convene America's brightest minds to help solve our most difficult problems. Whether the convenings are White House conferences or presidential task forces, the President should reach beyond his or her inner circle of advisors to determine how the federal government should work with states, localities and the private sector to help the American people adapt to the growing impacts of deadly weather.

Many convenings should take place in the first 100 days after Inauguration, but the president-elect need not wait until then. President-elect Bill Clinton set an example when he held a major economic summit in Little Rock a month before he was sworn into office. He assembled more than 300 corporate executives, small business owners, labor leaders, educators and economists for two days of televised sessions, most of which he moderated himself, to discuss long-term strategies for the economy.

The Democratic Party Platform already has prescribed what one of these sessions should be if Hillary Clinton wins the election. "In the first 100 days of the next administration," it says, "the President will convene a summit of the world's best engineers, climate scientists, policy experts, activists, and indigenous communities to chart a course to solve the climate crisis."

It will take more than one summit to chart that course, however. The destination is clear: Nations, political parties and communities must work together to restore the planet's carbon balance. But the details are complex. They will require investments, reinventions and tough decisions at a depth and speed we have not experienced since World War II. One of the decisions must be whether government and taxpayers should still be obligated to come to the rescue when people choose to live and work in harm's way.

***

Even before adverse climate impacts began appearing, floods were America's most frequent weather disaster. All 50 states have experienced at least one in the last five years. Virtually every body of water can cause flooding when the conditions are right. FEMA exaggerates a little but not much when it says "everyone lives in a flood zone."

During the 30 years that ended in 2014, floods caused an average of nearly $8 billion in damages and more than 80 fatalities per year. We Americans suffered more than $260 billion in flood-related damages between 1980 and 2013, including $67 billion from Hurricane Sandy alone. Today, more than $1 trillion worth of property and buildings are at risk just from sea level rise. Critical infrastructure - roads, bridges, power lines, water and sewage treatment plants, for example - is vulnerable, too.

Lately, "historic" and "unprecedented" flood disasters are becoming almost routine. There have been three "1,000-year floods" in the first seven months of this year and nine in the last six years. At this writing, flooding caused by Hurricane Matthew is still underway on the East Coast, with 26 fatalities so far and damages that are expected to be in the billions of dollars. Again, it's not going to get better. Because we are still dumping carbon pollution into the atmosphere, more severe climate impacts are in the pipeline. Scientists estimate that New York City, for example, can expect floods on the scale of Hurricane Sandy every 20 years, compared to every 400 years if the climate remained as it is today.

While we cannot stop climate change, we can change the way we deal with it. Several factors besides big storms contribute to deaths and destruction from floods. First, people are drawn to water. More than half the nation's population and housing is located along the Atlantic, Pacific, Gulf of Mexico and Great Lakes coasts. Millions more Americans live within reach of inland rivers. When it comes to living seaside, lakeside and near rivers, most people think closer is better.

In 1968, FEMA began mapping where the flood prone areas are around the country. But its maps have been based on past floods, not on the more extensive floods happening now and expected in the future. In fact, FEMA estimates that as much as 80% of annual floods losses already are taking place outside designated flood zones.

A second contributing factor is the strategy the federal government has long employed to reduce flood damages. There have been massive investments in flood-control structures. In the Flood Control Act of 1936, Congress gave the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers the job of building dams, levees, flood walls and channelization projects. The assignment reflected environmental attitudes that linger today. We believed that engineers could "control" nature and that we should deploy the Army's bulldozers to make war against rivers and to hold back the seas.

The Corps was not the only organization that built dams. There are more than 85,000 of them in the United States today performing a variety of tasks. Only about 4% are owned by the federal government. The rest are owned and operated by state and local governments and landowners, many of whom deferred maintenance over the years.

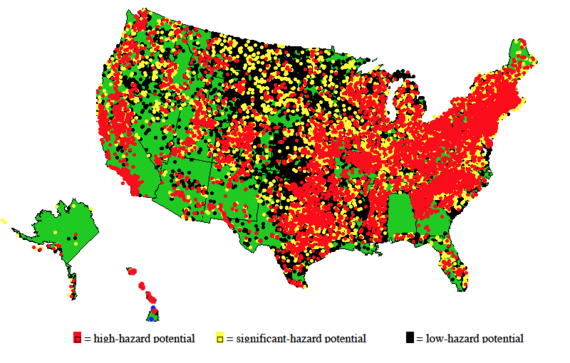

The average dam is now over 50 years old and past its intended lifetime. Many are in poor condition. In its assessment of the nation's infrastructure in 2013, the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) reported that 14,000 dams were classified as high-hazard in 2012, meaning that their failure would result in deaths. More than 4,400 dams were judged to be deficient, meaning they have hydraulic or structural problems that make them susceptible to failure. The ASCE estimated it would cost at least $21 billion to repair them.

Even in good repair, however, most flood-control structures were not designed to handle the level and intensity of flooding that is occurring today. From the beginning of 2005 through June 2013, there were at least 173 dam failures and nearly 600 episodes where interventions were required to prevent failures. A year ago, more than a dozen dams failed in South Carolina when catastrophic floods occurred there. Much of the destruction and death caused by Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans was the result of a failed levee. When a dam or levee protecting communities is breached or overtopped, the result is catastrophic.

A third factor in flood disasters is the government policies that permit if not encourage people to live and work in flood hazard areas. The federal government provides grants and loans for property owners to rebuild in floodplains after disasters. States must put up some of the money, but the federal cost is substantial. The Congressional Research Service (CRS) reports that from fiscal year 2002 to fiscal year 2011, outlays from the federal Disaster Relief Fund averaged $4.2 billion annually. Although Congress has taken steps to control federal spending generally, major weather disasters have "usually been funded outside traditional budget constraints," CRS says.

In addition, the federal government subsidizes insurance for floodplain property owners because private insurers have considered the coverage too risky. The National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) is supposed to be self-supporting, but it is not. When insurance payouts exceed available funds, FEMA borrows money from the Treasury. Today, the NFIP is $24 billion in arrears, largely because of the payouts it made after Hurricane Katrina and several other superstorms. The Government Accountability Office says it's doubtful the NFIP will ever repay the Treasury. In effect, taxpayers are the insurers of last resort for people who choose to live in hazard areas.

There's more. An investigation by the PBS program Frontline found that the NFIP is rife with lax management and that most of the funds meant for flood victims are going to consultants and insurance companies that earn profits of 30%. The Department of Homeland Security reports that without better management, the NFIP may be at risk of fraud, waste, abuse or mismanagement, but government auditors have found that FEMA "does not have the information it needs" to prevent abuse.

In the meantime, the weather is getting worse. "Since FEMA's first full year of operation (1979), there has been a steady increase in the number of emergency and major disaster declarations," CRS reports. "It is unclear what is causing the increase." Actually, the causes are very clear: More people are choosing to live and work within reach of flood disasters; government policies allow them to do so; many of the dams and levees built to protect them no longer can; and violent weather is becoming the new normal.

These problems have not been ignored by the Obama Administration, the Army Corps of Engineers or the many civil society organizations involved in floodplain management. In January 2015, President Obama issued an executive order that set new standards for all federally funded buildings, roads and infrastructure affecting floodplains. Federal agencies must now define floodplains based not on past experience, but on the best available climate science on what is likely to occur in the future. Importantly, federal agencies must not encourage floodplain development when there is an alternative. While the order doesn't say it, the alternatives should include the gradual evacuation of floodplains and/or the relocation of homes and businesses to higher ground.

Obama also directed federal agencies to encourage the use of natural systems such as watershed reforestation and wetlands restoration to help reduce flood damages. Still, Obama's top policy advisor, Brian Deese, acknowledges there is more work to do on adaptation to climate change. The need, he says, is "getting louder and louder" with disasters like Matthew.

To their credit, some communities and regions are not waiting for the feds. Ecosystem restoration projects are underway on the Gulf Coast, on the Great Lakes coasts and in the Mississippi River Valley. Some communities and regions are restoring the natural flood-retarding features of rivers, including wetlands and meander. In some cases, the projects are reversing structural work done in years past by the Corps of Engineers. And some U.S. communities have relocated some or all of their built environments to higher ground, an option that makes sense especially in the post-disaster rebuilding phase.

The tough-love option would be to agree that all Americans have the right to live where they want, but if they live in disaster-prone places, they are on their own. Taxpayers would no longer subsidize hazard insurance or reconstruction.

Adapting to a future of unprecedented storms and floods involves emotional issues like property rights, freedom of choice, and the tension between common sense, federal frugality and compassion for disaster victims. Next fall, the National Flood Insurance Program will come before Congress for reauthorization. Before then, the incoming president should reach out from her or his inner circle and convene many stakeholders to determine the reforms that should be on the table.

Next: America also needs a durable national energy plan.