I was 19 and he had died a hundred years earlier. At school we were terrified when the grammar tests asked us to analyze his complex sentences. It was repeated so many times that Jose Marti was the "intellectual author of the assault on the Moncada barracks," that we even imagined his body's presence on that morning of shooting and killing. On the political billboards his sayings - taken out of context - adorned a city submerged in the miseries of the Special Period.* I remember we sarcastically transformed some of them: "poverty happens: what does not happen is disgrace," we changed to, "poverty happens, what does not happen is the 174," referring to the bus route connecting Vedado with La Vibora.

There was no shortage of the dis-informed who blamed the Apostle for what was happening, and during the days of blackouts and very little food they visited various punishments on his plaster busts. The excessive distortion of Marti's ideas - repackaged according to the convenience of the powers-that-be - led dozens of my classmates to reject his work once and for all. Only a small group of us continued to read his love poems and free verse, preserving for ourselves another Pepe, more human, closer. I was then at the Pedagogical Institute, a springboard that would allow me to major in Philology or Journalism, two profession he had engaged in brilliantly. As presented to me there, he was a gentleman with an energetic face who must be unquestionably worshiped, officially defined as the inspiration for what we lived.

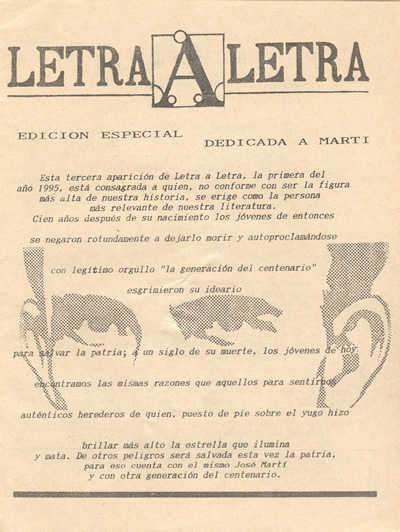

In the days leading up to the one hundredth anniversary of his death it occurred to me to write a small editorial for the newsletter prepared by several of us students. With the title Letter by Letter, the publication was filled with poems, literary analysis, and a section dedicated to the language mistakes we heard in the corridors of the Spanish and Literature Department. I wrote some brief and passionate lines where I said that we formed part of "another hundred-year generation" that would do our part to save the country from other dangers. That tiny violation of the established norms for interpreting the national hero ended with the closing of the modest periodical and my first encounter with the boys of the apparatus. Only they had the capacity to decipher and wield his writings, they seemed to want to tell me with that veiled warning, but I smiled through clenched teeth: I knew another Marti, more unmanageable, more rebellious.

Translator's note:

*The Special Period:The very difficult time in the 1990s after the fall of the Soviet Union and the end of its subsidies for Cuba.