Also aired on NPR's All Things Considered on August 17, 2012.

By: Eyama Harris

On the night of Stephanie Romero’s twenty-third birthday, she and her friend were attacked by a stranger. “My friend went outside to have a cigarette and there was this guy he came out he was harassing us,” Romero said. Then the man hit her and her friend. She was shocked.

“It was a total nightmare,” Romero said. “I think about it all the time. I’ve never gone through anything like that.”

After the attack, Romero’s friends and family noticed she was acting differently. She didn’t go out as often. Her weight started changing. She was really depressed. Later, doctors diagnosed her with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, or PTSD.

“I was like PTSD? I thought it was only for veterans,” Romero said. ‘But I found it’s not. It’s for anyone who’s experienced an event where you can't get it out of your mind and it takes over your life.”

I can relate. When I was fifteen my mom was murdered. I tried everything I could to deal with my feelings, including writing songs. But still, something was different about me. I noticed that I didn’t feel like my normal self anymore, not only mentally but physically. I was losing weight and my hair was falling out.

According to pediatrician Jamal Harris, that’s a pretty clear symptom that things aren’t going well.

Harris works a community health center in San Francisco. He says he sees teens with PTSD at his clinic all the time, and that many of them have physical symptoms related to their stress.

“Some examples in teens would be problems sleeping, weight gain, and just being frustrated,” he said.

It turns out a lot of those changes are due to hormones your body makes in response to stress. In some instances, this can be a good thing. For example, if a car comes at you all of a sudden while you’re crossing the street, your body produces a chemical called cortisol, which helps you react fast enough to move before the car hits you. But for people with PTSD, like Stephanie Romero and me, it doesn’t take a speeding car to set us off.

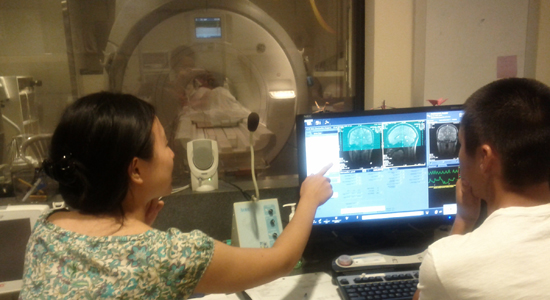

Dr. Amit Etkin and a research assistant help a participant into the bore of the MRI. Image courtesy of Amit Etkin.

In a Lab at Stanford University, scientists are using a technology called Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging or FMRI to study the emotional reactions of patients with PTSD.

“We know, for example, when they’re faced with a reminder of their trauma they don’t activate the circuitry we normally associate with emotional regulation, the ability to be resilient in an automatic effortless fashion,” said lead researcher Dr. Amit Etkin.

Etkin says cortisol -- the same stress hormone that causes physical changes in the body -- may also be responsible for the changes PTSD causes in the brain. “Elevated cortisol over time can cause death of neurons in the brain the kinds that don’t get replaced,” he said.

But that doesn’t mean PTSD can’t be treated. Scientists know talk therapy can be helpful. Now Etkin wants to understand how that kind of therapy might be repairing emotional connection in the brain. And he’s recruiting volunteers.

Including Stepahnie Romero.

Romero recently enrolled in Etkin's study, and today will be her first brain scan. It’s been ten months since her attack, and she says she is still having trouble feeling safe.

“Your life could change in the blink of an eye,” Romero said. “One minute you could be celebrating your birthday and the next you’re in the hospital and you don’t know how you ended up there.”

In a room on the other side of a huge glass window, Romero lies in an FMRI machine, which looks like a big tube with a small hollow center. I sit in front of a monitor as Etkin shows me different angles of her brain.

“A lot of what we look at with emotion is focused on certain regions of the brain,” Etkin says. “One of them is the amygdala which is really important not only for guiding your attention and focus on a threat stimulus, but also for affecting changes in your body. But someone with PTSD doesn't activate that circuitry well.”

Amygdala activation during an emotional task in PTSD patients. Image courtesy of Amit Etkin.

Etkin asks Romero several questions to help him identify which specific parts of her brain are affected by PTSD, and how she feels throughout the experiment. The goal is to see if she feels “in her body” Etkin says, “or does she feel, as many PTSD patients feel, which is out of her body or unreal.”

I can relate to that unreal feeling. It even started to hit me right there in the lab. Etkin hopes by understanding how that feeling plays out inside the brain, scientists will be able to come up with more ways of treating this disorder.

Whether it’s through singing, talking, neuroscience, or all of the above.

Originally published on Youthradio.org, the premier source for youth generated news throughout the globe.

Youth Radio/Youth Media International (YMI) is youth-driven converged media production company that delivers the best youth news, culture and undiscovered talent to a cross section of audiences. To read more youth news from around the globe and explore high quality audio and video features, visit Youthradio.org